Around a decade ago, an invasive fungal disease called myrtle rust reached Australia and began to spread like a plague through certain plants. The disease affects plants of the Myrtaceae family, which includes eucalypts, paperbarks and lilly pillies, and makes up 10% of Australian plant biodiversity/

In only a few years, myrtle rust has changed ecosystems by destroying trees and their canopies, wiped out whole species in certain areas, and taken an economic toll on industries that grow trees such as lemon-scented myrtle and tea tree.

The disease is a slow-moving ecological wrecking ball: surveys suggest it may drive at least 16 species of rainforest tree to extinction in the wild within a generation, with another 20 species at risk.

We have used RNA technology similar to that in COVID vaccines to create a highly targeted treatment for myrtle rust: a spray that can restore even severely infected trees to health in around six weeks.

At-risk species in remote places

The current approaches to dealing with tree diseases are limited. We can apply fungicides with a scorched-earth policy to kill all fungi, or we can breed plants for resistance to the pathogen.

Neither of these strategies is effective against myrtle rust. There are too many species to defend, located in some of the most remote places imaginable.

For example, one tree species on the brink of extinction from myrtle rust is called Lenwebbia sp. Main Range. It grows only on cliff faces in the Nightcap Range in northern New South Wales.

What’s more, many culturally significant and iconic trees in Australia and Aotearoa (New Zealand) are long-lived and cannot be swapped seasonally for resistant genotypes.

In the absence of a treatment for myrtle rust, the safeguard is to stockpile seeds to preserve genetics for future generations.

RNA interference

Our treatment for myrtle rust makes use of a molecular mechanism possessed by almost all plants, animals and fungi called “RNA interference”.

RNA is an essential molecule of life, similar to DNA, which usually occurs in single strands. When a cell detects double-stranded RNA (which in nature generally represents a virus or other threat), it triggers RNA interference to destroy the interloper.

The RNA interference system learns to recognise the threat, and will then also destroy any single-stranded messenger RNA that happens to match. This naturally occurring mechanism can be used to defend both plants and humans against pathogens, including fungi.

We designed double-stranded RNA that matched essential genes in the fungus that causes myrtle rust, and sprayed it on the leaves of infected plants. This triggered the fungus’s RNA interference mechanism, sabotaging the action of genes it needs to survive.

Treating severe infections

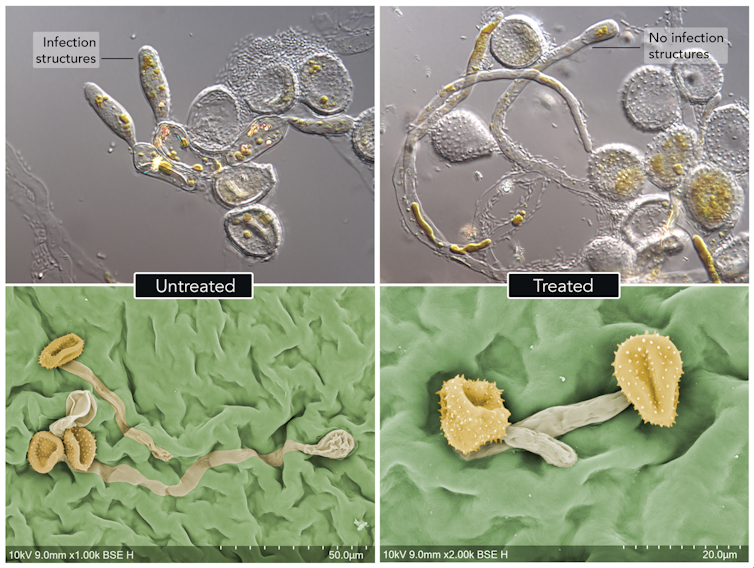

Rust fungi produce microscopic battering-ram structures called appressoria that are used to forcefully penetrate host leaves. Most fungal spores treated with double-stranded RNA could not germinate to produce their battering rams, and those that did were withered and powerless.

Double-stranded RNA can also be sprayed onto plants ahead of time to inhibit spore germination and prevent disease completely.

Next we trialled whether our RNA spray would stop and cure disease in severely infected plants. We saw that it inhibited the progress of the disease, and after six weeks even severely infected plants had recovered to a healthy state.

A targeted treatment

We wanted to make sure our treatment wouldn’t accidentally affect anything except the myrtle rust fungus, so we designed it using “barcoding genes” which uniquely identify the species.

Barcoding genes are excellent targets for RNA interference. They are generally identical among all members of a species, differ between closely related species, and usually control an essential cellular function.

The most closely related rust fungus to the pathogen that causes myrtle rust is found on a naturalised street tree in Australia called Albizzia lebbeck, but it is different enough to be unaffected by our treatment. It is extremely unlikely any unrelated organism would have an identical barcoding gene sequence to the myrtle rust pathogen, so we do not expect any off-target effects.

Another advantage of targeting a barcoding gene is our treatment has lasting impact. Unlike some other genes, barcoding genes cannot change by mutation without risking the organism’s survival.

This means the pathogen is less likely to evolve resistance. And if resistance against double-stranded RNA does evolve, the target sequence can be modified to match the rust again in a matter of days.

An integrated approach

There is no silver bullet to manage pathogens in native ecosystems and agriculture. The Australian government’s myrtle rust action plan recommends an integrated approach to control this destructive disease.

In coming years, double-stranded RNA can be incorporated to manage the epidemic of myrtle rust in Australia. We hope it will be especially useful in conservation, industry, and the treatment of individual trees – particularly culturally significant ones.

Rebecca Degnan receives funding from a University of Queensland Graduate School Scholarship, the Australian Plant Biosecurity Science Foundation, multiple philanthropic scholarships (associated with The University of Queensland), including the Joan Allsop Scholarship and the Gibbins Scholarship, and through the Plant Biosecurity Research Initiative as a current Ritman Scholar.

Alistair McTaggart received support from the University of Queensland and funding from the Department of the Environment and Energy under the Australian Biological Resources Study.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.