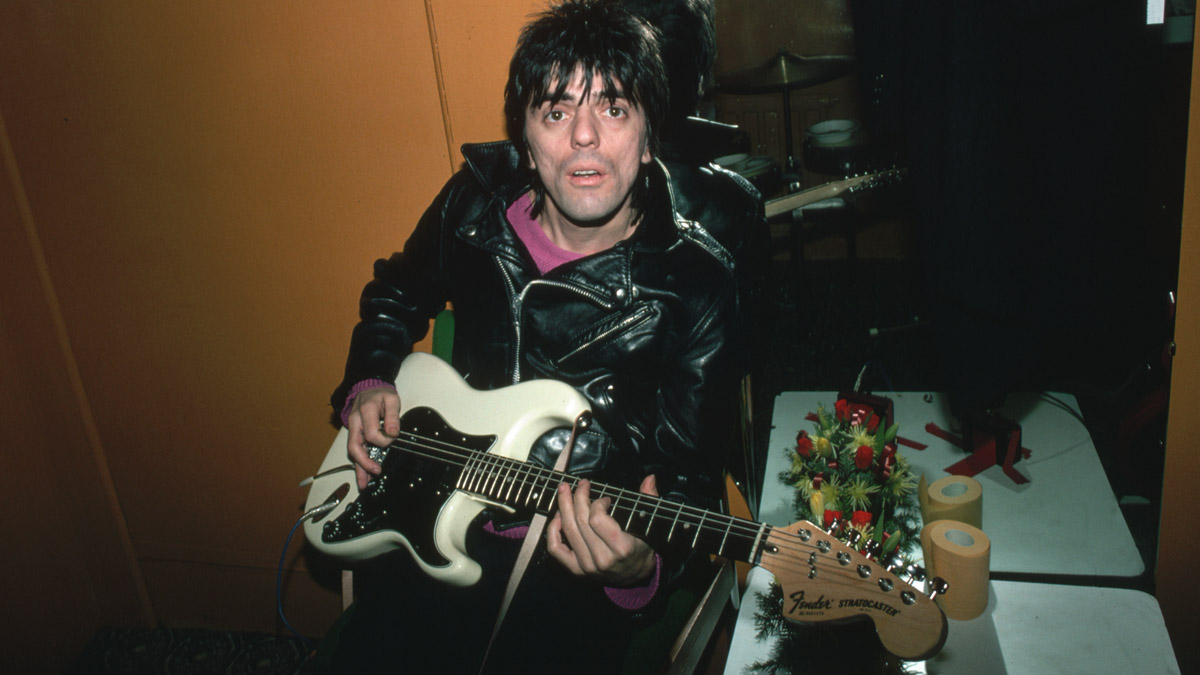

Even if you didn’t know that Frank Infante is a Jersey boy, it wouldn’t take you long to figure it out. Born and raised in Jersey City, next door to Hoboken and a tunnel or bridge away from Manhattan, the 71-year-old guitarist still has his gritty North Jersey accent intact.

It’s a tone and attitude thing, a certain street flair to the way he occasionally says “dis” for “this” or “dat” for “that.” When he talks about guitar parts, it sometimes comes out as “guitar pahts.” And as for the way he says “forget about it,” well, fuhgeddaboudit.

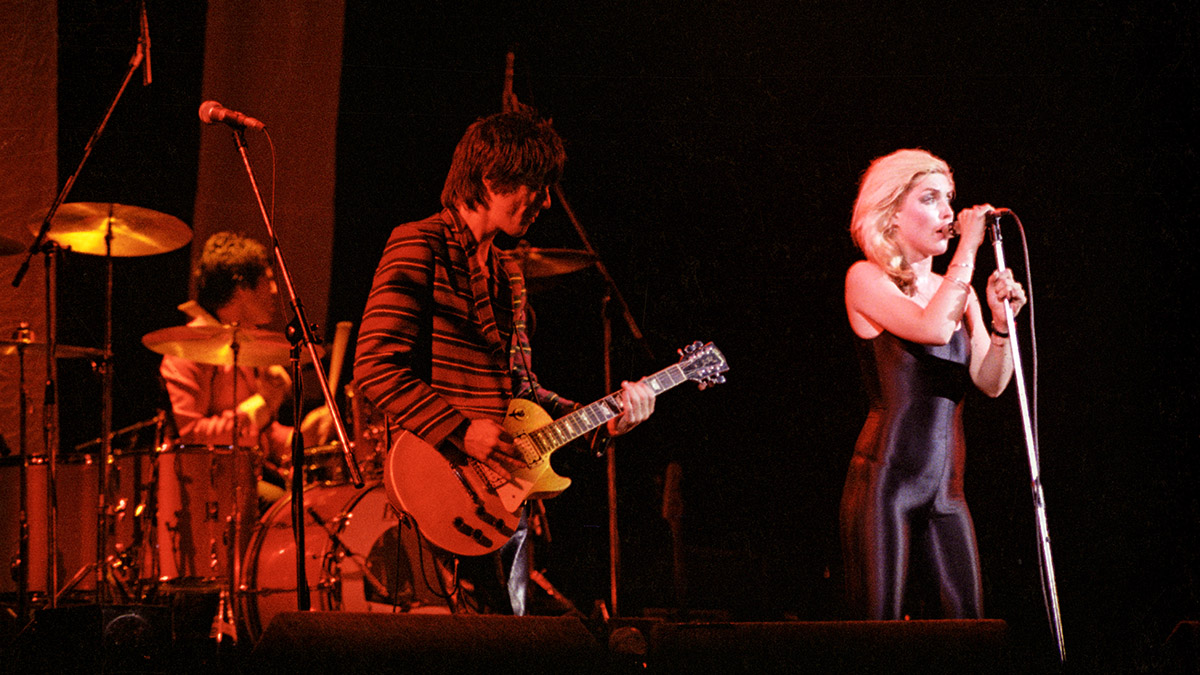

Back in the 1970s, Infante brought plenty of tone, attitude and flair to a New York City band that wasn’t lacking in any of those areas: Blondie, the pioneering, shape-shifting outfit, led by guitarist Chris Stein and singer Debbie Harry, who, over a six-year span, deftly – and in many ways, presciently – mixed punk and new wave with the sounds of Sixties girl groups, garage rock, disco, reggae and hip-hop.

The band was one of the first success stories out of CBGB’s, and by the time their run ended in 1982, they had dominated the airwaves with a steady succession of smash hits like Heart of Glass, One Way or Another, Call Me, The Tide Is High, Atomic and Rapture.

Infante remembers the downtown New York scene where it all started. “It was a cool time,” he says. “You didn’t have to be a brilliant musician – you just had to play your songs and have fun.

“Right before Blondie, you had the New York Dolls and other bands doing the androgynous thing. Then CBGBs and Max’s started up, and what we could call punk and new wave came in. CB’s was more of the college kids on a pseudo-intellectual trip, while Max’s was pure street rock ’n’ roll. Blondie played both places.”

During this time, Infante bounced between North Jersey and Manhattan, playing in a number of blues-based hard rock groups, most notably WWIII.

“I started using Gibson guitars and Marshall amps in that band,” he says. “It was also the first band I was in that did all-original material. We were a four-piece – guitar, bass, drums and a singer – so I did all the guitar parts and improvised a lot. We were four uncompromising delinquents. We’d show up at places and take over, just playing loud and heavy. I liked that approach.”

Soon enough, however, that approach and sound began to fall out of favor, and as Infante recalls, “a lot of the stuff I liked just wasn’t cool anymore. I never stopped liking it, but I could see things were starting to change, and Blondie was a part of that.”

Infante was already friends with Blondie’s drummer, fellow New Jerseyan Clem Burke. “Clem is from Bayonne, so he and I crossed paths in all of our bands,” he says. Eventually, he befriended Harry and Stein, then partners in romance as well as music.

“I liked Debbie and Chris as people first – forget about the music. They saw me play, and I’d go to their gigs. Blondie was different from a lot of the other bands. They were having fun and people liked them. There was an almost amateur quality to their thing, but it added to their charm. Gradually, I started sitting in with them. It was very casual.”

Blondie’s self-titled debut album, released in 1976 on Private Stock Records, found supporters in the UK and Australia, but it went otherwise unnoticed in the States. Ahead of the recording of their follow-up, 1977’s Plastic Letters, this time for Chrysalis Records, group members Stein, Harry, Burke and keyboardist Jimmy Destri were dealt a blow when bassist Gary Valentine tendered his resignation.

“Clem called me and told me about it,” Infante says, “and I said, ‘If you want, I’ll come in and play bass.’ They already knew me, so that was it. I wound up playing bass and guitar on the second record. After that, I stayed with the band.”

Infante proved to be a versatile and valuable asset to Blondie, and with the addition of Nigel Harrison on bass, he switched over to guitar just in time for the band’s ascent to the top of the charts.

Among his standout contributions are the rip-snorting riffs on One Way or Another (from the 1979 album Parallel Lines) the seething blasts on Call Me (a Number 1 single from the American Gigolo soundtrack) and in what is arguably his finest recorded moment, the gargantuan, whacked-out solo that bum-rushes Rapture (another Number 1, from 1980’s Autoamerican).

Sometimes, when a Blondie song comes on the radio, I’ll turn it up. It depends on mood, though. There’s other times when hearing it makes me feel a little stressed-out

Egos, drugs and personal resentments loomed large within the Blondie camp, and despite his solid and inventive performances, Infante’s relationships with Stein and Harry grew contentious. It all came to a head leading up to the recording of The Hunter in 1982, when he was pushed out of the group.

Although he won a lawsuit to remain a member, he was sidelined for the tour in support of the album (Eddie Martinez took his place). By now, Blondie’s drawing power had waned (they played to half-empty halls), and soon after they called it quits.

When the band eventually reformed in 1997, they again excluded Infante – and Harrison as well. The two attempted to sue the band’s founding members from touring with the name Blondie, but their case was rejected.

And when the group was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2006, Infante, Harrison and bassist Gary Valentine were blocked from performing, despite Infante’s onstage plea for unity.

Yet for all the acrimony, the guitarist harbors no ill will toward his one-time bandmates. “Sometimes, when a Blondie song comes on the radio, I’ll turn it up,” he says. “It depends on mood, though. There’s other times when hearing it makes me feel a little stressed-out. It goes both ways. But hey, the music is great – I’ll say that.”

Do you feel as though your contributions to Blondie aren’t always recognized?

“There’s a lot of misinformation out there. If you look on Wikipedia, it says that the band did Plastic Letters as a four-piece and that Chris Stein played guitar and bass. No – I played guitar and bass. I did all the bass.

“My involvement with the band is always called into question. I saw this video of somebody breaking down Heart of Glass. The guy said, ‘And here’s Chris Stein’s guitar part.’ I was like, ‘No, that’s my guitar part.’ That kind of thing’s been happening for years.”

Going into the studio to record Parallel Lines, was there a feeling that it was a make-or-break album?

“With Plastic Letters, we were an underground group. We were considered new wave or punk, but we weren’t a big band. Chrysalis Records certainly hoped we’d become something other than an underground thing. When we got to Parallel Lines, we worked with Mike Chapman as our producer. He was a hitmaker. Forget about it – he’s the best guy I ever worked with. Mike knew what had to be done.”

What was it like working with Mike?

“He was very different from Richard Gottehrer, who did Plastic Letters. Richard would have us do three or four takes, and then he’d pick the best one. With Chapman, you’d never find any bad takes. He’d erase the tape and then start over. So there was only one take – the good take.”

Did you and Chris Stein discuss how you two would divvy up the guitar duties?

“When I switched to full-on guitar, that changed the sound of the band dramatically. Chris and I had very different guitar styles. It wasn’t like we said, ‘You do this, I’ll do that.’ There were things Chris couldn’t play, and there were things I couldn’t play.

“Two-guitar bands are kind of tricky, but Mike Chapman sorted that out for us; without him, it would have been chaos. Usually, I’d go into a room with Nigel, Clem and Mike to work out a song. We’d figure out the arrangement, and after that I knew my parts.”

Speaking about the making of Parallel Lines, Mike Chapman called Blondie “musically, the worst band” he’d ever worked with, but he singled you out as being “an amazing guitarist.”

“Yeah, Mike and I got along really well. That might have contributed to some of the problems I had in the band. I was getting attention from him, and the others sort of resented it ’cause I was the new guy. All I know is we were doing what was happening, and it was all moving forward. Like I said, when I got involved with the band, it was sort of amateur, but good amateur – like Vaudeville.”

I never went in for too many effects. Occasionally, I used a bit of chorus or echo, but I usually plugged right into the amp.

Your riff on One Way or Another – what a dynamite sound!

“That’s probably my ’68 Les Paul goldtop through a Marshall. I had a Les Paul Deluxe and a Custom. I used all of them, but I think on that song it’s the goldtop. That was my guitar – put it through a Marshall, and that’s the sound. I never went in for too many effects. Occasionally, I used a bit of chorus or echo, but I usually plugged right into the amp.”

How did you feel about the band starting to embrace disco on Heart of Glass?

“I was fine with it. I mean, I didn’t think we were punk. The Sex Pistols were really good, but there wasn’t any variety. We had a lot of stuff going on. We were a pop group. I don’t even consider Heart of Glass a disco song; it was very experimental. Somehow, that beat appealed to people in discos, but it wasn’t the plan.”

Were you in the studio when Robert Fripp came in to play on Fade Away and Radiate?

“Oh, yeah. It was cool. We just knew him, so it was like, ‘Come down and play!’ Everything then was very positive. Fripp even played live with us a few times. He fit in with us because we weren’t doing the straight-ahead thing like the Ramones.”

The twangy, spaghetti Western guitar lines on Atomic – was that you?

“That’s me and Chris. What happened there was, Bruce Springsteen was in the next studio, so we’d see each other – ‘Hey, how you doin’?’ He had a Gretsch Country Gentleman, and I asked him if I could borrow it. That’s what I used on Atomic. Chris and I play the main riff, but I do the whammy bar part at the end of it. Then when you hear Debbie singing, ‘Take me tonight,’ that’s me doing all the other stuff.”

Sometimes you can refine a solo too much and it sounds stale. The Atomic solo had to be spontaneous. I probably would have lost it if we kept going

You played that brilliant solo on Rapture. Chris Stein said to me once that it’s one of his favorite solos you ever played. Was it really done in only two takes?

“It was. What happened was, I wasn’t involved with the track. Chapman and Nigel were in the studio, and I came down to hear what they were doing. Mike played me the track and went, ‘There! Come in there.’ I didn’t have a guitar on me, but Mike had these two Warlock guitars – a 10-string and a six-string.

“I plugged the six-string into a Marshall and ran it down to get an idea of what he wanted. Then I did it again and that was it. It just came out of me. There was no rethinking it. Sometimes you can refine a solo too much and it sounds stale. The Atomic solo had to be spontaneous. I probably would have lost it if we kept going.

Your rugged rhythm playing on Call Me made that song come alive.

“I think Clem and I were the only two people who played on it. It was a different song before I came in; they just had the drum machine beating. I played the guitar part on my goldtop, and Giorgio Moroder said, ‘Oh, wow, it’s totally different now.’ Again, I didn’t go home and work it out; it was totally spontaneous.”

The overall feeling I get from you about your time in Blondie is, it was fun… till it wasn’t.

“Yeah, sure. See, in the beginning, we didn’t know what we were doing. We didn’t know where this thing was headed and that we’d have these huge hit records. We were just going along. The more popular we got, things got weirder and weirder.

“There seemed to be some sort of problem going on, but I didn’t know what it was. There might have been some personality crap – egos or whatever. Mike Chapman was essential to the band. You needed him and the band to make it what it was. It was like a chemical formula.”

These days, do you have any kind of relationship with your ex-Blondie mates?

“[Laughs] You mean non-relationship. Actually, Clem I’m friends with. Nigel I’m friends with. Jimmy I’m sort of friends with. Debbie and Chris, whatever their thing is, I don’t talk to them. It’s not like I hate them; they’re just not around. I do feel disappointed, though, the way everything went down.

“I never even got to play the solo to Rapture live. All this stuff I’m supposedly known for, I never got to enjoy it. With The Hunter, they went out and hired some other guy to be me. They went on tour, but that didn’t work out and they had to stop right in the middle. That was the end of it, I guess. Debbie wanted to be solo or whatever. That went on until the reunion.”

Which you weren’t part of. And you weren’t allowed to play with the band during the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction.

“Yeah. The plan was for the four of them to go up and accept their awards, and then Nigel and I would go up. But what happened was, when they went up, I went up with them. I wasn’t supposed to, but I did. I said to Debbie, ‘Can we play?’ You know – me and Nigel. We were the ones who came up with the parts. We were going into the Hall of Fame, not these hired hands.

“I wasn’t trying to be a smart ass. Before then, I was trying to contact them, because every time I talked to the Hall of Fame, they said, ‘You’ve got to talk to Debbie.’ But she wasn’t communicating. I thought it would have been a good thing if she said we could play. Everybody would have been happy.

“The sad part is, all the members who did those records are still alive. But we never got it together to play again. I’d be interested to see what would happen if we got the whole band and Mike Chapman back together to do an album. It would be nice to do it while we’re all still around.”