In the summer of 1992, my family gathered in central Minnesota for my grandfather’s 70th birthday. We were there to celebrate William J Svrluga Sr – father, golfer, husband, engineer, grandfather, Cubs fan, cheapskate, retiree. Seven of us joined in the celebration: Bill Sr’s wife, Ruth, my grandmother; his two sons, my father, Bill Jr, and my uncle Dick; their wives; my younger brother, Brad, and me.

At one point, maybe between the walleye and the turtle cheesecake, the conversation hit a lull. Uncle Dick filled it. “OK, Dad,” he asked. “What are you most proud of in your life?” I think I half expected my grandfather to say the time he shot even-par 72. What could be better than that? This was chitchat, brag-about-the-family stuff, set up on a tee. Instead, he knocked us over with his response. “D-Day,” he said.

I remember it as both matter-of-fact on his part and jarring to the rest of us. Why, if D-Day had been so important to him, had we never heard about D-Day? We knew he had been there, part of the Allied invasion of Normandy. Right then, it became apparent how little else we understood. As the 75th anniversary of D-Day approaches, I’m again aghast that I thought he could have answered anything else.

We arrived in Plymouth, England, April 19 1944, and in those 47 days preceding the invasion of Europe we saw and helped prepare, in our small way, the greatest mass of men, material and ships in history for what was to come.

For our first two weeks we had nothing but manoeuvres until we could see them in our sleep and for a while we began to wonder when and if that day would come. For we had built our expectations to such high levels that nothing seemed to satisfy us.

In the spring of 1944, Bill Svrluga, then 21, set sail on the USS PC-568, a submarine chaser in the PC-461 class. The ship was diesel powered, 173 feet long, 450 tons fully loaded, with room for 65 Navy men. In the weeks leading up to D-Day, the ship ran supplies and spies off the coasts of France and Belgium. The missions came at night. They were exhausting.

We know this now because, in July 1944, my grandfather wrote it all down. Bill Jr, my father, stumbled upon the document in a dining room sideboard when he was high school age. But his mother caught him there, told him he wasn’t to read it and sealed it back up.

My father filed away a memory of the journal he hadn’t read. A half-century later, after his parents died within a month of each other, he was cleaning out their suburban Chicago condo. He had it in mind to keep his eyes open for the journal. And, in all the detritus that comes with separating what to keep and what to toss, there it was, in what seemed to be a random drawer.

How this manuscript came about, none of us knows. It’s 16 typewritten pages, and neither my father nor my uncle ever remembers Bill Sr typing. In passages, it’s brilliantly written and remarkably self-aware. Bill Sr wrote it, it seems, on 11 July at a rest camp in England – after the horrors of D-Day but before his next mission, to the Mediterranean. It reads like both a history book and a movie script.

It seemed fantastic as we did our work each night so close to the enemy, sometimes right under their noses and then making a mad dash back to England before daybreak with what seemed unbelievable luck. ... Our days were occupied with sleep, rest and preparation for our next mission.

Why we were never interrupted or discovered by the enemy is beyond explanation. God and luck must have been with us because many of the other ships that were assigned to our squadron never came back. Our orders, when deciphered, were: ‘If trapped by enemy, jettison ship.’ ‘Jettison’ meaning to completely destroy the ship and material so it could not come into their possession.

Our nerves were beginning to tell of the strain we were going through as each night passed. We were not allowed to go ashore during the day or mingle with anyone because of the information someone might let slip from his lips. Each night as we headed back into enemy territory and the coast of England slipped into the sea, I knew that not only I, but each and every one of us wondered if ever we would live to see the break of day.

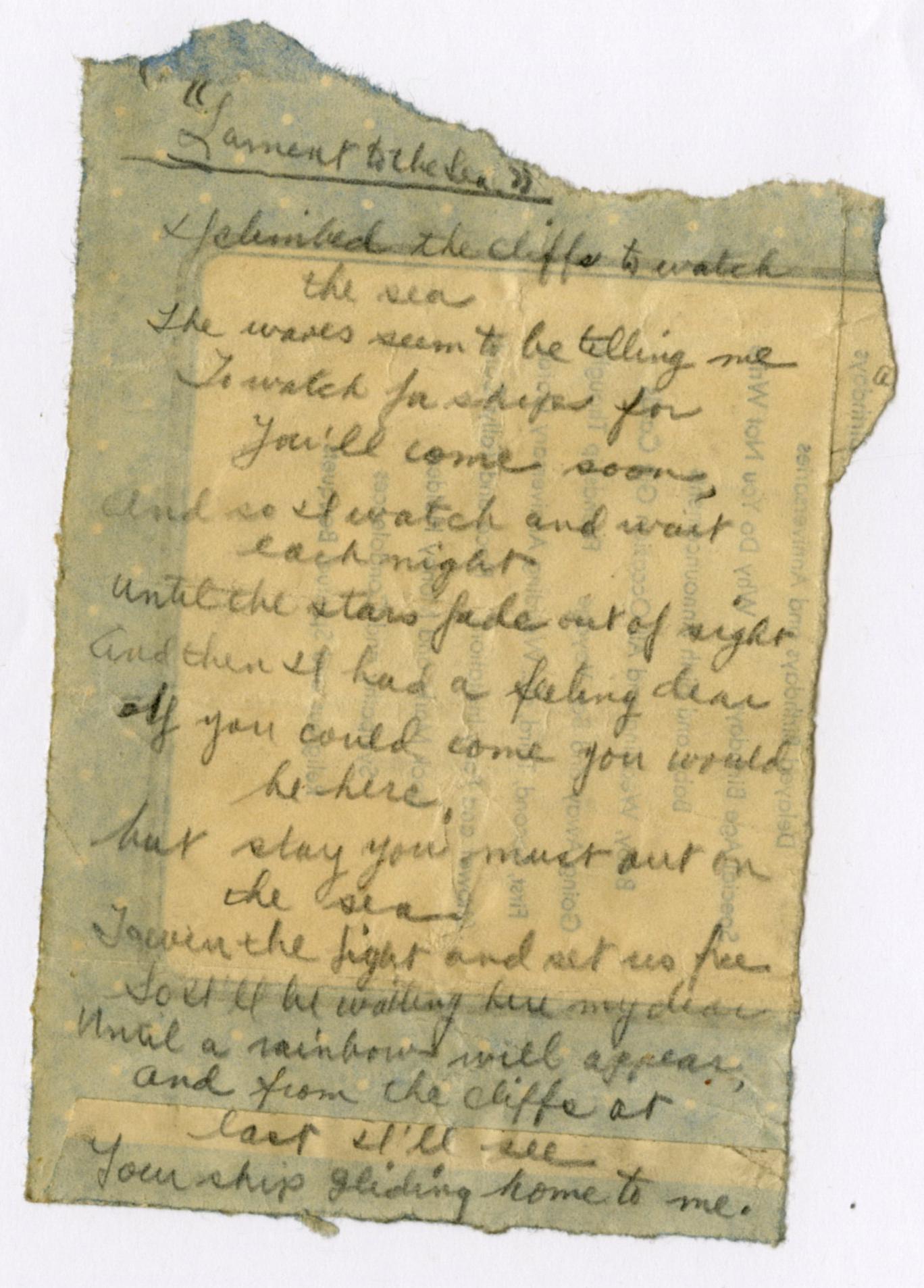

This narrative wasn’t the only thing my grandfather wrote during the war. There were also letters – boxes of them. (My father found the letters while cleaning out his parents’ attic, before they moved into their assisted-living condo.)

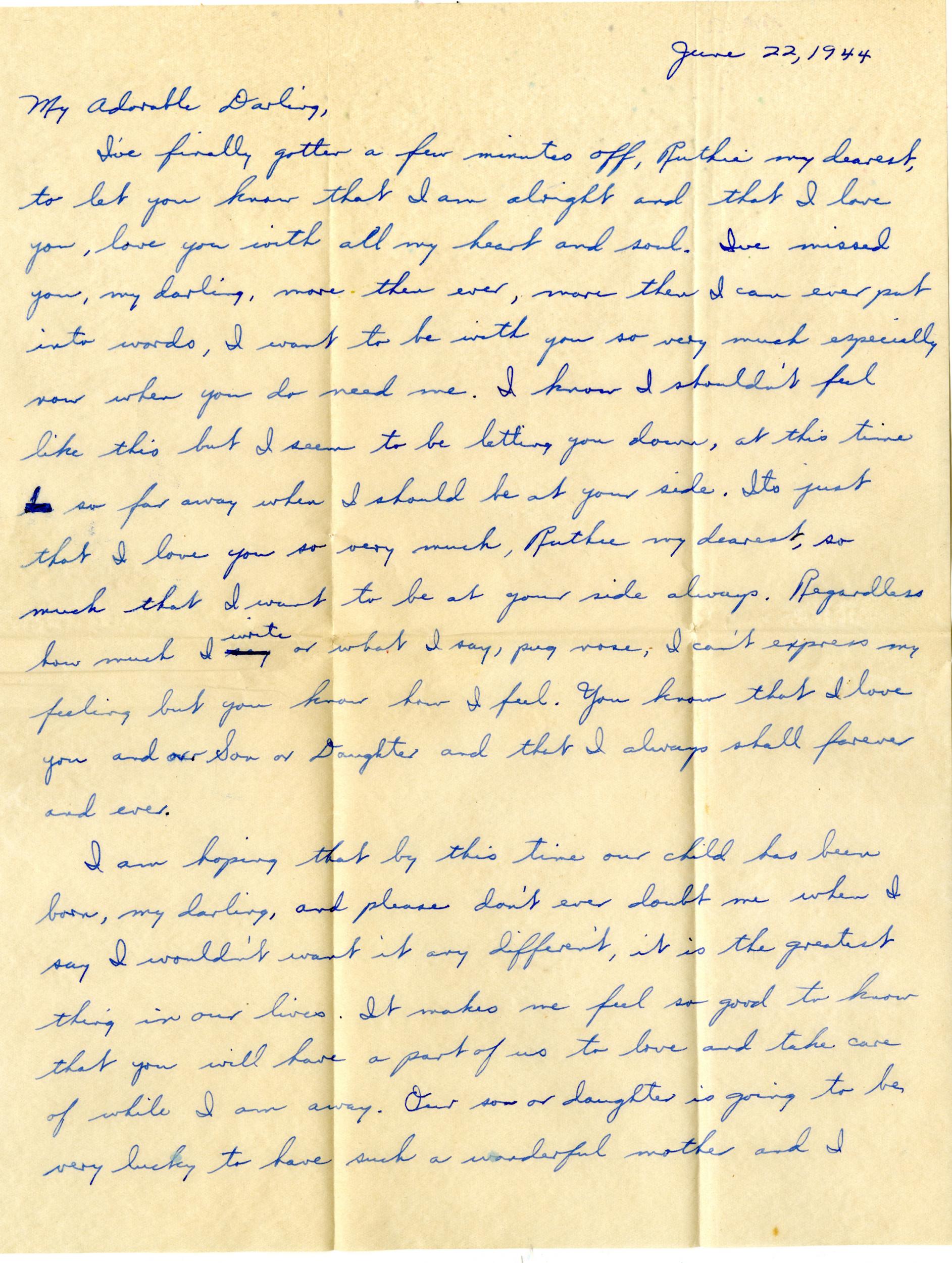

These were love letters in the purest form, sweet and tender. Bill Svrluga and Ruth Crowell had met in Revere, Massachusetts, at a roller-skating rink; they were married on 4 May 1943, at Riverside Church in New York. Ruth got pregnant that fall. My grandfather went to war the next spring. Quickly, he began writing to her, day after day of adoring prose.

From 10 May 1944, weeks before D-Day:

I try to write every day we are in, darling, but if I miss 3 or 4 days or a week you will know that I am at sea, so please do not worry about me. Can I tell you once more before I close that I love you, Ruthie my darling, and I never shall stop so long as I live. We have received no mail as yet, but hope to soon. Please keep writing.

“I Love You, Bill

From 1 July 1944, weeks after D-Day:

Ruthie if I only knew that you were alright and that our son or daughter was there with you, if I could hear just one little word it would relieve my mind so very much. I keep thinking that something might have gone wrong. ... Our child is probably in your arms by this time, my darling, but until I hear that you are safe + sound it shall seem worse then [sic] any Invasion.

The letters – a sailor missing his wife, wondering whether he’ll ever see his unborn child – are heart-wrenching enough on their own. But there was another layer to my grandparents’ story: during the war, my grandmother got pregnant again, this time by another man. She would give birth to a daughter. My grandfather returned to his wife after the war; the daughter would be raised by my grandmother’s mother, in New Hampshire. My father and his brother – my uncle Dick – would grow up knowing this girl as their grandmother’s youngest daughter, not their half-sister. As my grandfather told my dad years later, “There was never a question. That’s just how you handled it.”

My uncle, in particular, remembers the post-war Svrluga household in the Chicago suburb of North Riverside, Illinois, as gripped by tension. Dinner began, nightly, at 5.15pm. It was over by 5.30. It wasn’t just the war they rarely talked about. For the most part, they didn’t talk about anything.

Dick remembers that, one day when he couldn’t have been more than five years old, his mother opened a drawer, showed him Bill Sr’s letters, and told him that his dad had suffered during the war. As they sat on the living room floor, the drawer open with all those letters, Dick got the strong impression that they were private and personal, that he should not touch them, much less read them. He never did.

Somehow, my grandparents’ marriage lasted. And despite all they went through as a couple, there are indications that each understood the other. Indeed, my grandmother was the only one living in that little house who had a clue as to what Bill Sr had endured. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the term post-traumatic stress disorder didn’t yet exist. There were, though, what we would now consider easily diagnosable signs. My uncle remembers one spring, when a rabbit was eating vegetables in the backyard garden. His dad threw a rock at it. He hoped to scare it away. Instead, he killed it. Upon that realisation, Bill Sr broke down, sobbing uncontrollably. The family didn’t understand, couldn’t understand, how much death he had seen. That day, Ruth had to help her husband back inside.

The crack of dawn with the hills of England in sight once again meant safety and rest for a few hours with another successful night behind us. Upon the completion of our thirty first mission we were relieved, thus ending the longest thirty-one nights that I or any other man had ever lived or will live. Nerve wracking nights of coming so close to death and yet at times in the stillness it seemed as though the enemy was millions of miles away.

As we headed back to Plymouth for a few days of rest and recreation we knew that we would not have to wait long for the day the whole world was impatiently looking forward to. ... [W]e prepared ourselves and received our final orders on June 2. From then until that eventful morning it was just waiting and waiting with our nerves drawing to a greater tension as each day passed. ...

We were ordered to Portland Harbour, Weymouth, England and from there we embarked on our never forgotten journey. Once again the shores of England slipped into the sea and as we took one last look we knew that some of us would never see it again. We had known this feeling before but somehow this seemed the most important day of our lives.

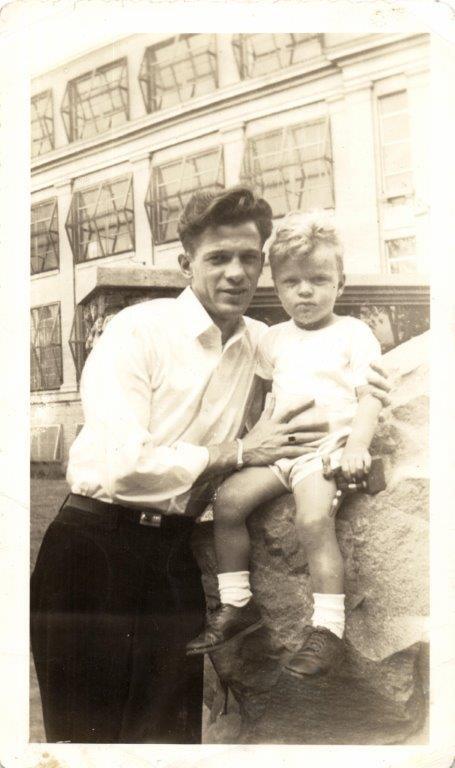

As my grandfather embarked on his D-Day mission, he was thinking about his still-to-be-born child – the son who would become my father:

As we crossed the English Channel, meeting thousands of ships, it seemed as if they came from nowhere, my mind went back to my wife that in a few days or weeks would give birth to our child. My dangers were minor compared to the thoughts that ran through my mind, of what could happen to her in giving birth to our son or daughter. Perhaps to some they were foolish thoughts but to me the life of my wife meant the world itself. I did hope and pray that if something did happen to me she would not hear of it until after our child was born. There was a job to be done and if it was done with success I knew I could get to see them both again, my child for the first time.

My grandfather returned to Normandy on the 49th anniversary of D-Day in 1993 – best to steer clear of the crowds that would flood to the 50th. It was just Bill Sr and Ruth, and we didn’t hear a whole lot about it. Only later did we find out that Ruth had temporarily lost track of her husband; she found him on Omaha Beach, overwhelmed and bawling.

In the mid-1990s, my grandfather was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, and by the turn of the century, he showed obvious signs. His hands shook. His head bowed. Mentally, though, he remained sharp for years. And by late in 2002, he was self-aware enough to know: He could still travel abroad and appreciate what he saw, but that wouldn’t last forever.

In a phone call, he made clear to my father that he wanted to go back to Normandy again. My father was enthusiastic about the idea but had a normal question: Why? Why, when he had already been, was it important to go back?

My grandfather’s answer: “I owe it to the guys.” And so, we agreed to go, we rushed to go, to be there on June 6, 2003, not a major anniversary but an anniversary nonetheless.

Besides my grandmother, the only key family member who couldn’t commit was my younger brother, Brad. He was getting married that summer. He had showers and bachelor parties and a wedding and a honeymoon to account for. Too much time away. He had to stay home.

While near Chicago for a shower thrown by friends of his fiancée’s family, Brad met my grandfather for our favourite activity with him: golf. Bill Sr was the best player I have ever known. Rounds with him were nothing short of a treat.

That day, Brad played nine holes; Bill Sr rode alongside in the cart, playing no shot more than 100 yards, all he could do anymore. Afterward, they ate lunch on the patio. The family trip was upcoming, so Brad felt emboldened to ask about it. What he found was a willing conversational partner, opening up about D-Day. My brother pushed further.

“How far offshore were you?” Brad wondered. Bill Sr looked out beyond the patio. “You see that tree over there?” It was, by Brad’s estimate, maybe 50 yards away. None of us had considered that he’d been remotely that close to shore. He wasn’t on the periphery. He was in the middle.

When Brad left the patio, he called me from the car. “I think,” he told me, “I have to figure out how to come to France.”

Our task was a dangerous one, we were to drop marker buoys along the invasion beaches before H-hour, so that the landing craft could unload their troops in the correct places. After H-hour we were to try and draw enemy fire away from the troops landing, by making a nuisance of ourselves to the enemy. As we drew nearer [to] the dark French coast our planes began to drop their bombs and we could see thousands of paratroopers dropping from the sky by the glow of the fires caused by the explosions. The invasion of Europe had started, for us, at 0200 June 6, 1944. Almost at once it was broad daylight and then all hell broke loose, it seemed as if the whole world was being shaken by its roots.

At 0630 the first wave of troops hit the beach and as I saw them falling – dead and wounded – as if some one were using a hugh [sic] fly-swatter, I thanked God for the first time that it was the Navy I was in instead of the Army.

Thus started what seemed the endless task of firing into the beach, evading enemy gun fire, picking up the dead and wounded, who were hit by machine gun fire from the air and the shore. As the morning wore on a great wave [of] despair came over us. The enemy was still strong and all that we had accomplished was just a bare foothold on the beach with the seas beginning to kick up. But as nightfall came it brought with it German aircraft who played hell with us all night but after eighteen hours of heavy fighting our beachhead was temporarily established.

We set our alarms for pre-dawn on the morning of 6 June 2003. Our hotel was a little more than a 20-minute drive from Omaha Beach. We wanted to be there as the sun came up. We wanted to be there for H-hour.

Fifty-nine years earlier – an hour after the sun rose, right as an inconceivably massive Allied force sat off the coast, poised – the USS PC-568 floated near the western edge of what would be known as Omaha Beach, right in line with the tiny village of Vierville-sur-Mer. According to a chart showing the Allied formation in Joseph Balkoski’s book Omaha Beach: D-Day, June 6, 1944, my grandfather’s retelling of his ship’s position to Brad was accurate: his distance from the shoreline was best measured not in miles or fractions thereof, but yards.

Standing on the beach that morning, my grandfather started talking. What I remember most is how much he remembered – the shape of the coast, the Allied men climbing the cliffs only to be repelled by the Germans, the weather, the sounds, the horror, the hell. Looking inland, he pointed to a bluff. He remembered, in the moments before the attack, seeing a lone figure riding a donkey, carrying milk. “And then I looked up,” my grandfather said, “and – poof! – he wasn’t there anymore.”

The beach was almost empty, just a few stray souls walking there for the same reasons we were. As we clustered, listening to my grandfather’s accounts of the day, a middle-aged man approached. He asked if we were American. He said he was from Virginia. Then he looked directly at my grandfather.

“Were you here?” he asked.

“I was,” Bill Sr said.

The man extended his hand. “Thank you,” he said. “Thank you.”

So it was, the same old story night and day, day and night, caring for the wounded, loading ammunition, firing guns, burrying [sic] the dead until at times you almost wished that the next bullet was intended for you.

On June 9, 92 hours after H-hour all enemy guns were knocked out on the beach, giving us our first chance to realise what had actually happened and what we had gone through. Why we are still alive and afloat, God only knows. It seems impossible. We managed a few hours sleep, in rotation, under our guns. Even though it was a cold hard deck it was the sweetest sleep of my life.

Our captain was wounded June 15 by machine gun fire from enemy planes but refused to leave the ship. Many others had small wounds but somehow managed to stay at their gun stations. As for myself I was beginning to get dizzy spells, at times I could barely see through my gun sights but there was no such thing as stopping now.

We all began to wonder if it would ever end. All we wanted was to get some sleep, as many of us were beginning to pass out from sheer exhaustion. Some were cracking under the terrific strain of seeing nothing but wounded, dying and dead from the beginning of the fifteen days and nights. Somehow I managed to control my nerves but as each day passed it became harder and harder. At times I wondered if there was anywhere in this world where it was peaceful and quiet, we hadn’t managed two hours of sleep since D-day. The ship that was to relieve us was sunk, so there was only one alternative and that was to keep going.

On 21 June, during a nightly air raid, a German bomber was shot down, and the left wing of the aircraft crashed into the engine room of USS PC-568.

Now, for the first time, we buried our own dead – those whom we knew so well and lived so close to. As a prayer was said from the Bible over them I wondered if tomorrow night someone would be saying a prayer over me.

The USS PC-568 was ordered back to England, for repairs. Less than 48 hours later, with only 39 men left aboard, it was sent back out to sea, acting as a communications and patrol ship along the French coast. Men and supplies arrived constantly. The ship was eventually ordered into the harbour of the city of Cherbourg, well to the west of Omaha. Cherbourg was being bombarded by the Allies but was still partly in German hands.

Then I could understand why it had taken us so long to prepare for this great task. It seemed impossible that the human minds of our Admirals and Generals could perform this great feat with such accuracy and speed. Though it has been mentioned in previous pages, the burying of the dead some of which had been floating in the filthy sea for days, was truly an ordeal. To look at a mangled mess that was bloated and green with salt blisters, eyes still open and bare feet swollen to three times their normal size was a sight that no one of us shall ever forget; not to mention the smell. The burying of them in the sea was namely three steps. First to dismantel [sic] them of their life jacket; second to remove dog-tags; third to weight them with iron and give them to the slimy sea.

[O]n June 28, 1944, I set foot on French soil for the first time. It seems as if I had stepped into an inferno of hell instead for as our Army slowly captured the city, our air force with there [sic] well placed bombs, were destroying the enemy defences. To add to the confusion the Germans were dynamiting everything they could lay their hands on. We worked as we never had before bringing 200 wounded aboard in two hours; working with a speed unbelievable for 39 men who, just a few hours before had seemed to be on the verge of collapse.

Yes it was true we had saved the lives of two hundred American Soldiers but we were not impressed or joyful over what we had done. Instead we were bitter because of the day in which we could have rested for a few hours was taken away from us. Perhaps to those who may ever read this, it may seem cruel in what I have just said but at that time, with a long dark night filled with enemy planes ahead of us, those were the truthful feelings of our men. For our bodies and minds were too dazed to function properly, we craved for rest nothing else.

With the ending of June 28 came a day that shall live in each and every one of our minds forever, the climax of this dreadful dream we had been living for the last twenty-four days. At 0315 on the morning of June 29 ten miles from LeHarve, France, we hit a mine. An explosion that seemed to rock the face of the earth and tried so very hard to kill us all.

My father was born on June 29. My grandfather, some 3,300 miles away, had no way to know.

I with four other men were blown completely off of the ship in to the water, a wet but soft landing. We were the luckiest of all, for we escaped without a scratch. In that split second of the explosion I died a million deaths but the cold water of the ocean brought me quickly to my senses. ... There is not much that can be said of the six men who were standing near to where the mine hit, death came to them swifetly [sic], for not a trace of any part of their bodies was ever found. ... Now, there were only 17 of us left for in that ordeal 16 had been wounded and six killed.

When we left the beach, we travelled first to the Memorial Museum of Omaha Beach, and eventually to the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial. Buried there are 9,380 Americans, most of whom lost their lives on 6 June 1944, and in the operations that followed. The Wall of the Missing accounts for 1,557 more who were never recovered.

I remember walking around almost aimlessly, together but separate. At one point, I found my grandfather standing motionless, staring at the graves, then the graves beyond those, then the graves beyond those. I walked up to his side and stared with him.

“What are you thinking?” I asked, surely awkwardly. It was silent a moment. We both stood there. “Coulda been me,” he said. “Coulda been me.”

We who are left, modern science shall never again cure our wounds, for our injuries are in our minds and we alone, with time and rest, will decide on our future and fates.

Now the quiet rolling hills of England have seemed to dim out those awful memories of the past that we are all trying so hard to forget. I know there is nothing in this world that will ever take those memories away from us, regardless of how hard any of us may try.

This morning of July 11 also brought to me the news I had so impatiently been waiting for. My wife had given birth to our child, a son, on June 29. It was as if the world were lifted from my shoulders when I knew once again that she was safe and well.

Was it just a coincidence? Or was it faith? On that day that had marked my life so bitterly with suffering and death, my wife had brought into this world our son. ... Now I have only but one desire and that is to go to those I am so proud of and whom I love so very much, my wife and child.

In a few hours we will be on our way once again, a new ship, a new crew heading for the Medeterranean [sic] Sea for what we expect to be the invasion of southern France. ... Once again it is good-bye to the shores of England and to those seventeen of us who have watched those shores disappear on the horizon so many times before, came those same thoughts: ‘shall we ever see England again?’ For we knew the coast of her land meant life, safety and our mission completed successfully once again.

As I leave this time I now have my son waiting with his monther [sic]. Waiting for me so that I may come home, to help bring him into a world of what we all hope shall be peace amongst all men, fighting so that he and his loved ones shall never have to bear the scars of war.

Yes, I have a great deal to live for and somehow I have a feeling that I shall come back to the both of them, but if it is God’s wish that I do not, I shall leave with a prayer, that my son shall live a better life and a safer life in his world than the life lived in the world of his father.

My grandfather died in 2006. By the time he left the Navy on 5 November 1946 – more than six years after he enlisted – he had been awarded five medals, including the World War II Victory Medal, the American Defence Service Medal and the Good Conduct Medal. All were listed on his notice of separation from the Navy, which my uncle found after he died. We had never heard about any of them.

© Washington Post