Under the record industry's model for success, Tool should have been dead and buried a long time ago. Whereas most bands “get it while the getting is good,” releasing albums and touring to support them every year and a half or so until the public loses interest, Tool disappear from the public eye for excruciatingly long periods between albums and tours. Some critics have even joked that their new album is titled 10,000 Days because that’s how long it took them to make it – although 27-plus years is quite an exaggeration, even by Tool’s standards.

“Despite what everyone thinks, it didn’t take us five years to make this record,” says Tool guitarist Adam Jones during our interview in Los Angeles. His point of reference is the group’s previous album, 2001’s Lateralus. “We took a long time off after the last tour.”

What’s more, he adds, during that time, singer Maynard James Keenan participated in his numerous side projects, which include A Perfect Circle. “We started making this album a little more than a year ago.”

While their record label would undoubtedly love it if Tool released a new album every two years or less, Jones believes the ample length of time between albums works to the band’s advantage.

“Our records don’t sound like other people’s records, where they release them a year apart and they end up sounding like a bad cover band version of themselves,” he says. “Each record sounds different from the one before it. Those long breaks we take give us time to absorb what’s going on around us and grow. I think that shows on our records.”

Tool have defied the record industry’s penchant for overexposure. They maintain their mystery by not plastering their faces all over their album covers and videos, and by performing mostly in the shadows of the stage while overwhelming the audience’s senses with stunning visuals and sound. Chances are good that even the most devoted Tool fan would not recognize Keenan or Jones on the street. But the band prefers that listeners focus on the music rather than on the group’s “image” or intimate details of the members’ personal lives.

“I get great emails from our fans,” says Jones. “My favorite was from this girl who wrote to me on MySpace. She said, ‘I finally figured it out: Lateralus was written to The Passion of the Christ. It’s so amazing how it links up. I want to thank you for doing that.’ I wrote her back and said, ‘Cool. You figured it out.’ Of course we wrote that album way before The Passion of the Christ came out, but I loved how she tried to link our music to something else.”

It’s hard to imagine what influences Tool fans will hear on 10,000 Days. Expanding upon the ambitious approach of Lateralus, the new album features dizzying polyrhythmic lines and epic song structures in which ideas weave together or simply crash into one another.

Its vast palette of sounds includes Talk Box and “radio” guitar solos from Jones, bassist Justin Chancellor’s slithering fretless bass and off-kilter riffs, and Danny Carey’s stunningly complex drum patterns, throbbing electronic noise, and funky Middle Eastern percussion. Keenan’s vocals are often heavily processed with distortion or mixed down among the instruments so they’re more like an instrument themselves.

“This record sounds so huge,” says Jones. “That’s because the vocals aren’t mixed way out front. When you mix the vocals out front, it crushes the force of the band behind them.”

Whereas Tool’s previous albums were produced by David Bottrill (Peter Gabriel, King Crimson), this time the band chose to produce 10,000 Days themselves, enlisting Joe Barresi (Melvins, Queens of the Stone Age, Bad Religion) to engineer and mix the album. Jones notes that, although other people may have previously received production credit, the band have actually produced themselves from the beginning.

“Every time we’ve made a record, our songs were already worked out by the time we started recording,” says Jones. “But every time we’ve worked with someone, they’ve wanted a production credit. We’d say, ‘Okay. Why not?’ But to me a producer is someone who comes in when you don’t have your songs worked out, or you want to be a certain kind of band and you need someone to come in and make you into that type of band. It reminds me of American Idol – or as I call it, the Gong Show Rip-Off.”

Although rumors of Tool’s breakup regularly surface – fueled largely by Keenan’s tendency to become immersed in side projects during the band’s downtime – Jones insists that the relationship between the four members has never been stronger. Absence, it turns out, may not only make the heart grow stronger, but may also be the key to enjoying a long, successful career as a band.

“I’m really lucky that the three other guys I work with are so incredible,” Jones says. “It’s not perfect; we don’t all see eye to eye. We fight, not with our fists, but we disagree or get into arguments when one person wants to go in a certain direction and the others don’t. But we all respect each other and try to work it out. It’s a four-way arrangement. We split everything four ways. I think that’s why we’ve been together as long as we have.”

The songs on 10,000 Days are structured more like classical music: they start in one place, go somewhere else, and end in a completely different place altogether. It’s as if the songs are telling a story in a linear fashion.

“Thanks. That’s the thinking. This is going to sound really pretentious, but it’s more emotional. For us, writing music is very therapeutic. You get to these different states, and it’s almost like you’re entertaining yourself. You’re leading someone by the hand, but the hand you’re leading is your own. I don’t get choked up when I hear other people’s music, except in a few rare instances. The Melvins did something that I thought was absolutely fuckin’ beautiful. But if we write something I really like, I get teary eyed.

“I’m the kind of guy who can cry really easily. The really long song on the record that starts very classically and builds is my favorite song that we have ever done. I get really choked up whenever we play it. I was really worried where Maynard was going to go with it, but he nailed the lyrics on that one.”

That song is quite a tour de force. You really don’t notice how long it is while you’re listening to it.

“I’m 41, and I never thought about that stuff as a kid. I never bought a record and thought, ‘Oh, this song is long.’ I never thought Stairway to Heaven was a long song. I loved how there was this part and then there was another part that was completely different. If you’re making music for all the right reasons, people are going to be receptive to that and appreciate it the same way you did when your were writing it. It’s not radio friendly, but we’re not…”

You’re not exactly radio artists.

“We are and we aren’t. We’ll pick a single that we think will do well on radio and we give it to them in its entirety. A band we knew told us that they’d edit their songs for radio, but even if they edited a song down to four minutes, radio stations would edit it down to three minutes. So we just give it to radio as is. We can't control it anyway. It's their world, and if the song does good, great.”

You have an extensive background in the visual arts. Do you tend to visualize things when you’re writing songs?

“I like soundtracks and I like film. I try to think in those terms, but it’s more emotional. How can you describe something without telling the person what it is? If you wanted to explain the yellow color of that Kodak [film] box without showing the person yellow, how would you do that? You might be able to do it by saying, ‘You know when you feel like this or when this has happened or you’re sitting under a tree?…’”

How did you prepare for this record?

“There’s always the influence of music, film, art, and the other things that drive me. I’m usually inspired by my environment and whatever is making me happy or mad. By the time we decide to get together again and start jamming, Justin and I have a huge amount of material. We bring it in and everybody rips it apart like wolves. We explore every avenue and path of it and then choose the paths that work best with one another.”

I hate when art is forced, when you look at something and go, ‘God, give me a break!,’ because you can tell that that person was trying to be artistic and show off themselves as being some weird, arty guy

All four of you seem to be constantly bursting with creativity.

“But in our different ways. If you sat each of us down and asked, ‘What are your views on politics? What kind of music do you like?’ you’d find we all have very different answers. What the four of us do is what Tool is, and that’s where that magic happens.”

A lot of bands have opposite forces, a yin and a yang. What is Tool’s yin and yang?

“That’s a pretty broad question. I don’t know. It’s a lot of subtle things: like Justin’s from England and I’m from here. We have similar interests in comedy, music, and art and similar views on life, but at the same time we often disagree about certain types of music, art, and philosophies. The main thing I like about us is that there’s a friendship, an understanding of communication, compromising, and working together.

“Basically, we’ve been married since 1990. It’s those normal things you’d have with any of your close friends. Sometimes we fight and disagree, but we’re big enough to go, ‘Well, what did you want out of that?’ ‘I wanted this.’ ‘Let’s meet halfway.’ There’s a lot of negotiating going on. It’s not always structured like that; it’s something that we feel. It’s kind of like asking me what I like and don’t like about my mom.”

Let’s try the opposite approach then. What do you all share in common?

“All of the members of Tool agree on sacred geometry, which is a study of taking everything that’s complicated about the world and everything that’s concentrative of our world and breaking it down to the simplest things: simple patterns, shapes, colors, vibrations… all that kind of stuff. To me that is what Tool is, because everyone in my band gets that. My band. It’s my band. I asked Maynard to play with me, so Tool is my band.

“I hate when art is forced, when you look at something and go, ‘God, give me a break!,’ because you can tell that that person was trying to be artistic and show off themselves as being some weird, arty guy. It’s not from the heart. Life is short, and it’s so rewarding to try to get to a certain point.”

Is writing songs for Tool fun?

“No. It sucks. It’s hard; it’s a long process; it can be grueling; but it’s fucking rewarding. When we’re doing a video, throughout the whole process I’m going, ‘I’m never doing this again. This sucks. Everyone is against me. I’m just trying to get something done.’ But as soon as we’re done, I’m like, ‘Let’s make another one!’”

I’ve always been interested in rhythm. I wrote the main riff to Aenima, but it was based on Danny showing me how to play three-on-four

What specifically influenced you while you were making this album?

“I got into studying polyrhythms and experimental math, seeing what different kinds of math worked together. If they didn’t work, I’d try to figure out why and determine what I had to throw in to make them work. I listened to a lot of classical and electronic music as well as a lot of metal, especially the heavier stuff. I tried to get into as many paths as I could.”

You can hear a lot of polyrhythms, not only within how you, Justin, and Danny played together, but also within your own playing. You can especially hear that in some of your tremolo and delay effects, where the tempos seem to change freely yet they remain in sync. How did you do that?

“I had some custom pedals made. Our engineer on this album, Joe Barresi, is a pedal god, and he knows everyone. I used a Gig-FX Chopper pedal, which has a nice tremolo. We had them work on the pedal so I could go from a clean sound to tremolo and control the tremolo speed as well. The pedal lets me slow it down and speed it up, which really lends a lot of power for creating motion when we’re going from one part to another.

“I told Joe that I wished I could do this with any pedal. He came back with this thing that looked like a wah pedal, but you plug other pedals into it; it blends between your clean sound and the pedal effect, so you can fade the effect in gradually, like a breath, instead of just clicking the pedal on.”

You also played a Talk Box solo.

“I always wanted to use a Talk Box – I love Joe Walsh [who famously used a Talk Box on his solo hit, Rocky Mountain Way] – but I never wanted to use it for the sake of using it. We wrote this song and I knew that it was the song where the Talk Box would work really well. Joe Barresi knew [Heil Talk Box inventor] Bob Heil and contacted him. He was just awesome. He gave me free stuff, told me what mics worked best, and showed me how to get the best sound.

“My friend who works for the Eagles’ booking agent talked to Joe Walsh and gave him my number. A while later I got a message from Joe on my answering machine: [imitates Walsh] ‘Adam Jones, this is the Talk Box fairy. Give me a call.’ I called him and he was totally cool and gave me a lot of advice. I think that the Talk Box on [the Eagles'] Those Shoes is really amazing, especially how the harmonies are in each speaker. I’m really happy with how the Talk Box came out on this record.”

You explored a lot more textures and tones this time. You even played a few genuine guitar solos.

“We had a little more time to experiment. We had everything written before we went into the studio. Maybe only five percent wasn’t ready, and we always have at least one song that we build in the studio. That’s been a rewarding process.

“I talk to people who are in bands and who write their whole record in the studio. They don’t know what they’re doing, and they have a producer come in to help them write songs. We didn’t have a producer this time. Joe Barresi just recorded the record and mixed it, although he did have some input in the process.”

The album features a lot of interludes in which the guitar or drums drop out entirely and the sounds get very small and intimate. Then when everything comes back in, it sounds even bigger because of the contrast.

“That’s the Melvins school of writing music. You learn very quickly that discipline plays a huge part in your writing. You learn that not playing can be just as powerful as playing. You need to let things breathe. I could fill up every little space with feedback or something, but why? That silence just makes the times that I do play have much more impact.”

Sometimes you play your guitar more like a percussion instrument.

“I’ve always been interested in rhythm. I wrote the main riff to Aenima, but it was based on Danny showing me how to play three-on-four. One hand is doing three and the other is doing four. And he taught me this rhythm that goes ‘Pass the goddamn butter.’ That made me wonder what other rhythms I could explore.

“My nephew Joe was in this Arizona drum corps, and his teacher really liked our music and Danny’s drumming. They played Tool arrangements. Joe sent me a tape of it, and we loved it.

“When we played in their town, we had them open for us. I hit up Joe to show me some rhythms, and he showed me weird beats you can play with one hand while you play straight four with the other hand. That really comes in handy. It’s like playing a Chapman Stick or a Warr guitar [both instruments are played via two-handed tapping]. I’m nowhere near that level, but I really enjoy that mode of thinking.”

You’ve got to try new things, but we didn’t want to go into the studio and turn on every plug-in and try every new pedal

The polyrhythms, arpeggiated patterns, and mathematical aspects suggest the influence of King Crimson.

“There’s a little bit of that. [Robert] Fripp showed me some stuff. So did [King Crimson/Mr. Mister drummer] Pat Mastelotto, and [King Crimson multi-instrumentalist] Trey Gunn. Those guys are giants, and it was great to learn from them.

“I’ve also learned a lot from Meshuggah. They’re not so much about polyrhythms as they are about trying different things together and seeing where they meet. They may play in three, then in five, then in four, in one progression of riffs; if the drummer is playing over that in four, they’ll see where the rhythms meet up. It’s so exciting. Meshuggah are modern prog-rock as far as I’m concerned. That influence is also on this record.”

Some of your guitar tones are very focused in the midrange and sound small, almost like they’re coming from a radio, whereas you previously went for a wall of sound. Did you experiment with a lot of effects or amps?

“When I play I’m constantly using my volume control. That’s why I use tube amps instead of solid-state amps. When you pick softly it’s clean, and when you pick hard it’s distorted. I’ve started using a volume pedal so that I can manipulate the attack by swelling the sound. It’s something I learned from Robert Fripp. And a couple of times I used a weird tiny speaker that Joe had.

“My second favorite lead on the record was recorded using something called a ‘pipe-bomb mic,’ which someone built for Joe. It’s a footlong piece of round brass pipe that’s maybe an inch and a half in diameter and sealed on both ends. An old guitar pickup is mounted off-center inside of it, and it’s hot-wired, so it works as a mic.

“Joe put it out there with the rest of the mics and the gear that I was using, and it got this beautiful radio-like distortion. We ended up pulling out everything else and leaving in just that mic.

Every guitar, every tube amp, is entirely different, even if it’s the same make and model. Each has a different character

“We had a good time. I’ve always admired the guys in King Crimson because they always pulled new technology into their sound, but they were so tasteful with it. They were intrigued by it and used it artistically.

“I’ve seen a lot of other bands use new technology, and I often wondered what they were thinking. I don’t want to rag on Todd Rundgren – I like him – but I thought he was working too hard on the modern stuff. I saw him in 2000 and I was really disappointed.

“You’ve got to try new things, but we didn’t want to go into the studio and turn on every plug-in and try every new pedal. It was a matter of figuring out what the song needed.

“It’s also about experimentation. That’s the process with us. People ask us to explain what we do, and I can’t. The only thing I can explain is that it’s completely experimental and based on the most concentrated aspects of what we like. After it’s done, we connect the dots; that’s what we’re doing right now. We’re putting the songs in sequence for the album; we’re connecting the dots. It’s not like we wrote a song knowing that it’s going to be the last song on the album.”

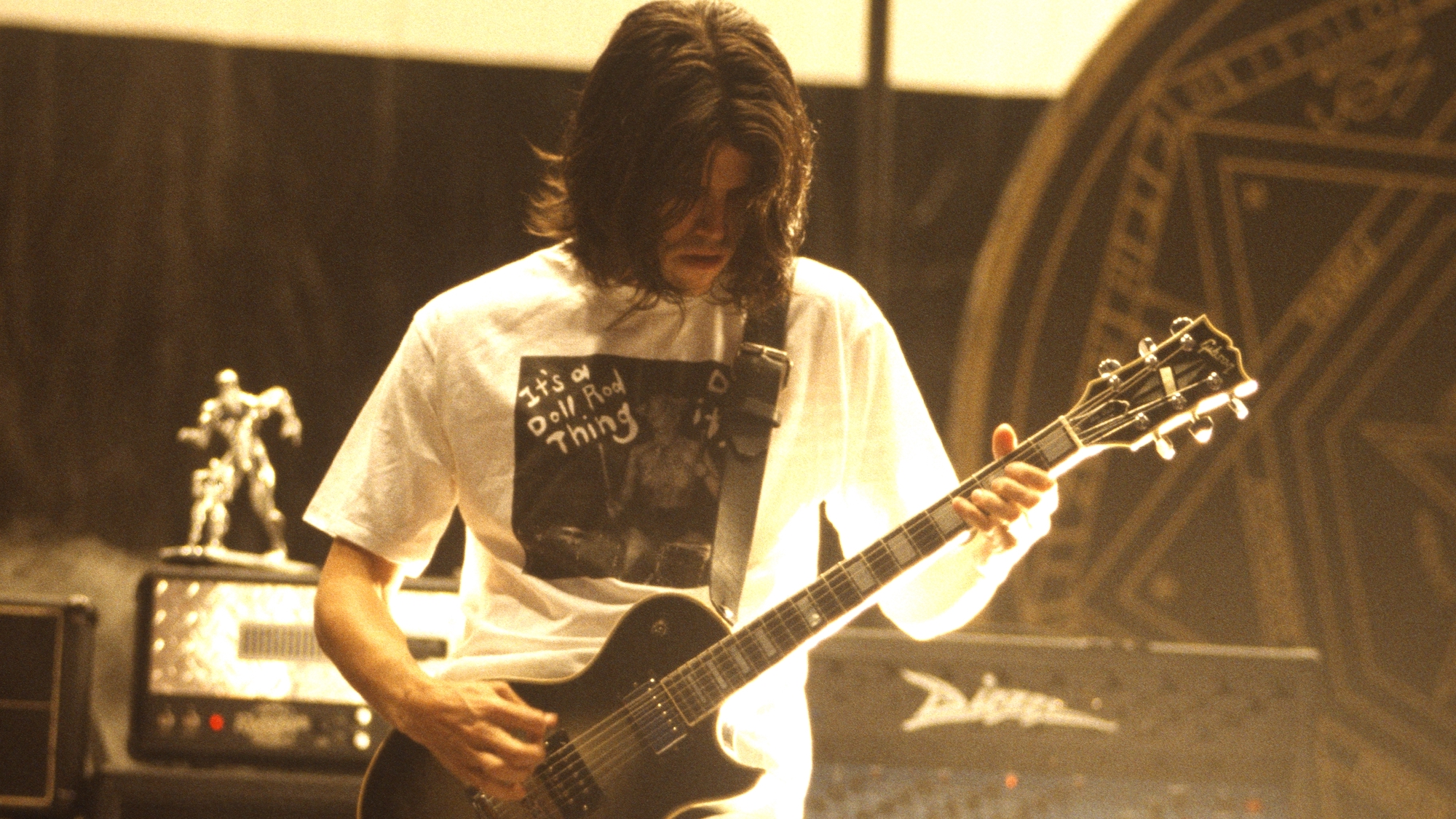

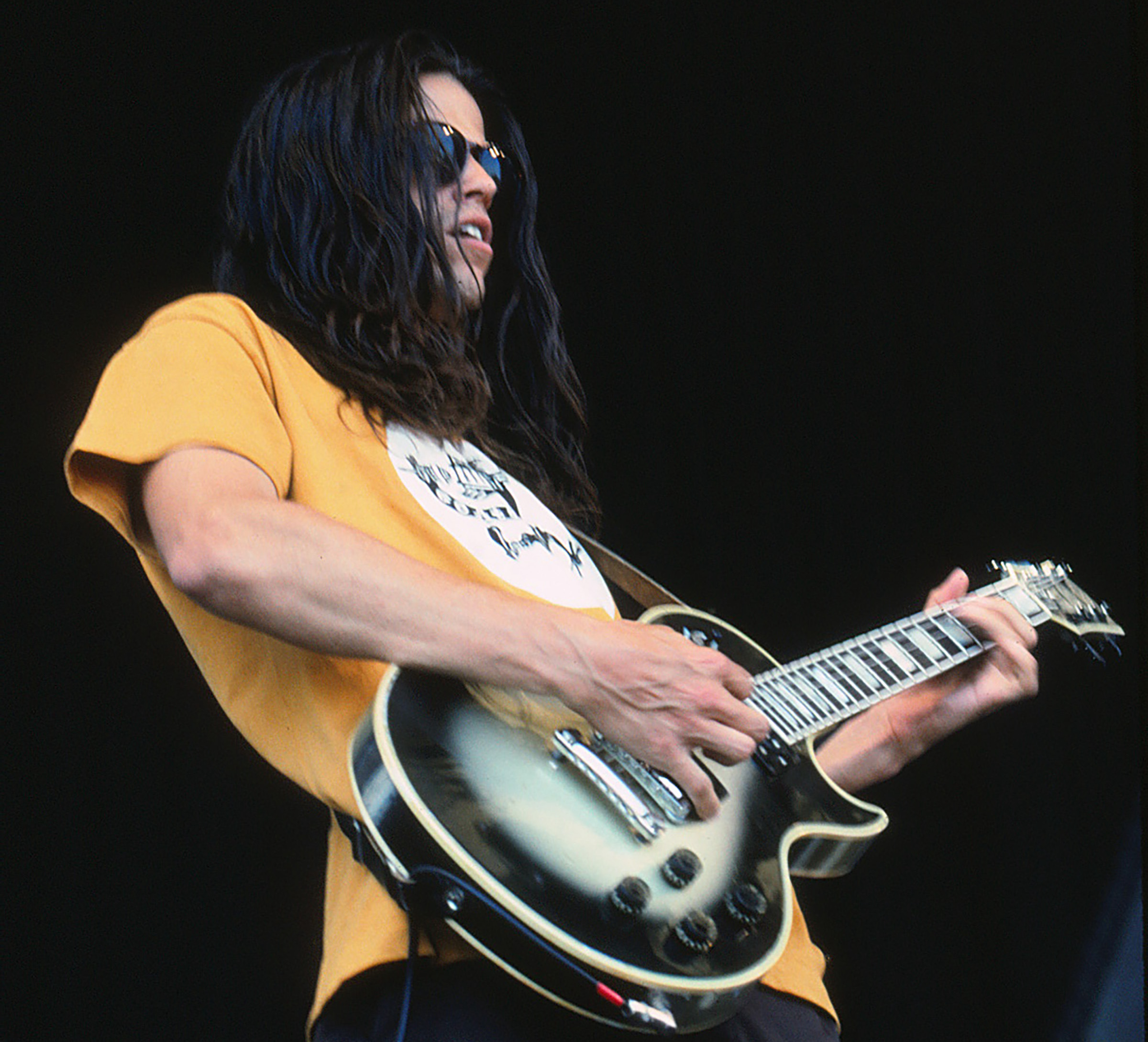

Are you still using your Marshall and Diezel amps? Have you made any significant changes to your equipment rig?

“I don’t know yet. After hooking up with Joe Barresi, I became really impressed with Bogner amps. I was also impressed with this Rivera amp and a Peavey amp that Joe had. I would never think to play a Peavey amp, but it’s awesome. Joe calls it his ‘Mississippi Marshall,’ but if I was to play live right now I would play my Marshall and two Diezels through my Mesa/Boogie cabinets, which are amazing. There’s nothing like them. They really put out that low end.”

Did you play any guitars other than your Les Paul?

“I might have used different guitars for really quiet parts. Every guitar, every tube amp, is entirely different, even if it’s the same make and model. Each has a different character. Sometimes something would sound good, but it wouldn’t be exactly what we needed. We would experiment.

“Joe has so much equipment, you wouldn’t believe it. We both have a shitload of guitars, and we would just go through them and try different stuff. It’s all a blur to me now. I couldn’t tell you what I used on any particular part because I tried so many different things.

“We had at least four different amp setups with different cabinets ready to go at any given time. It was usually a combination of three amps. If that wasn’t working we’d pull something out and put something else in.

“I learned a lot from Joe. He always listens to the note and the character of that note. He really studies it. A lot of people do that, but they don’t take it farther than their conscious thought. If you really pay attention, you can hear what it’s missing, what you like about it and what you like about something else so you can combine those sounds.”

It sounds like you’re playing an E-Bow on one song…

“Please don’t say that I play an E-Bow. They say on their web site that I use one, but I don’t. If I used one, I’d say it, but I don’t. I asked Robert Fripp what is the best way to get sustain – meaning what equipment should I use, what strings, what kind of amp. He said, ‘Attitude.’ And he’s right. If you play that note and you want sustain out of it, you’ll get sustain.

“I have overdrive pedals, a wah, and my amp. I have one of those blue Coloursound fuzz pedals and a Foxx Tone Machine, which they just reissued. Those are great for sustaining notes. I’ve really tried to get a note to hold as long as it can and make it sing or make it bend on its own. The pickup’s polarity will hold the note’s vibration and can cause it to feedback so it keeps going and sounds like an E-Bow.”

It takes a lot of discipline to play that way. Most guitarists want to play as many notes as they can instead of wrenching every possible texture out of a long, sustaining note.

“I grew up with that. In Seventies rock there were leads in every song. I used to like Frank Zappa, but I thought that when he played a lead he would go on for way too long. In the Eighties everyone had a gimmick. Michael Angelo [Batio] had four necks, so the other guy would have to have six necks. Tom Morello is a friend of mine, and he comes from that school where it’s got to have a crazy sound and he’ll do wacky things. He really gets off on that. But I was always bored with three-hour solos.

“I think Joe Satriani is amazing, but after three songs he puts me to sleep. I used to play no solos. I’ve come out of my shell a little bit. If it’s tasteful and it’s what the song needs, it’s okay. There’s a big difference between talent and gimmick.

“A lot of fellow up-and-coming guitarists will ask me if I think they should go to Guitar Institute of Technology or just join a band. I ask them what they want to do: ‘Do you want to learn technique? Do you want to learn how to play scales? If so, you should go to GIT. But if you just want to play music, you should start jamming with your friends and start a band.’”

There’s something to be said for forming your own identity and not caring about everything else that’s going on around you. That’s kind of what you guys did when you formed Tool back in 1990. You were here in L.A. during the tail end of shred mania, but you found your own niche, and eventually the music world caught up with you.

“That wasn’t really a conscious choice, though. Maynard and I had read this review where we were compared to one type of music and the review bagged on us. That happens a lot.

“When we started out, metal was moving away from glam and getting harder, thanks to bands like Corrosion of Conformity. Critics compared us to that. Then Nirvana hit and we started getting compared to grunge. Then Nine Inch Nails got big, and suddenly critics thought we were an industrial band. Whatever group we were being compared to, that group would go, ‘Fuck Tool. They’re not like that.’ Maynard put it perfectly. He said, ‘We fell in the cracks.’ That’s what we are: we’re the band that fell in the cracks.”

A lot of critics feel the need to pigeonhole and classify groups. The problem is that a lot of musicians have very diverse influences, and as a result their music defies categorization.

“I’m glad you say that. I’ve done interviews where I was asked, ‘Don’t you think music is worse than it’s ever been?’ It’s exactly the same. When I was a kid, there was always pop shit being played on the radio; there was always American Idol kind of shit going on. But there was also always something that was against the mainstream, and it was kind of popular and underground. If anything is different today, it’s that corporations are involved in the business; there are no handshake deals any more.”

Tool’s music can be so incredibly powerful and violent that it causes audiences to react to it in a violent way as well. Yet it’s obvious from Maynard’s lyrics and even the band’s attitude that you care about people. How does it feel to be onstage and seeing people in the crowd pummeling the shit out of each other?

“You can’t tell people what to do. It’s like kids. I don’t have any kids, but I used to work with kids, and my friends, brother, and sister have kids. One thing I always see is that you need to let your kids be themselves; then you try to guide them through that instead of trying to make them be like you. The relationship with an audience is almost like a sexual one. It’s not sex; there’s no nudity; but it’s this intimate thing where you have to let these people be what they are.

“Our last record was very healing, very ‘think for yourself.’ The attitude on this record is more about putting people in their place, but without controlling them. We’re saying, ‘You have an opinion on this, but this person who went through that whole thing may have a different perspective. You should think about that before you say something. You’re not bad for thinking what you thought, but you need to consider the perspectives.’ There’s a lot of that on this record.”

Maynard’s line, “Who are you to wave your finger?,” really stands out in that respect.

“Yes. That’s the pot calling the kettle black. Maynard writes all his lyrics and he’ll pull in subject matter from our mutual ideas. It might be something that happened to him, but it’s always something that we can all relate to, like telling a friend to back up for a second and try to see things from a different perspective. Maynard can explain these things better, but suffice to say, it’s all positive. At the end of the day, there’s a lot of love from our band. I’m not kidding.”

This interview first appeared in the June 2006 issue of Guitar World.