It's truly said that sometimes life is stranger than fiction, and the one such incident is that of Indrani Mukerjea's-- the media baron who was accused of killing her daughter Sheena Bora. It was August 25, 2015, when Indrani Mukerjea's life changed forever. On a day when she was looking forward to a birthday celebration in her family, she was taken to the Police on the charge of murdering her daughter. What followed next was Indrani Mukerjea's trial by the media, which made her a household name.

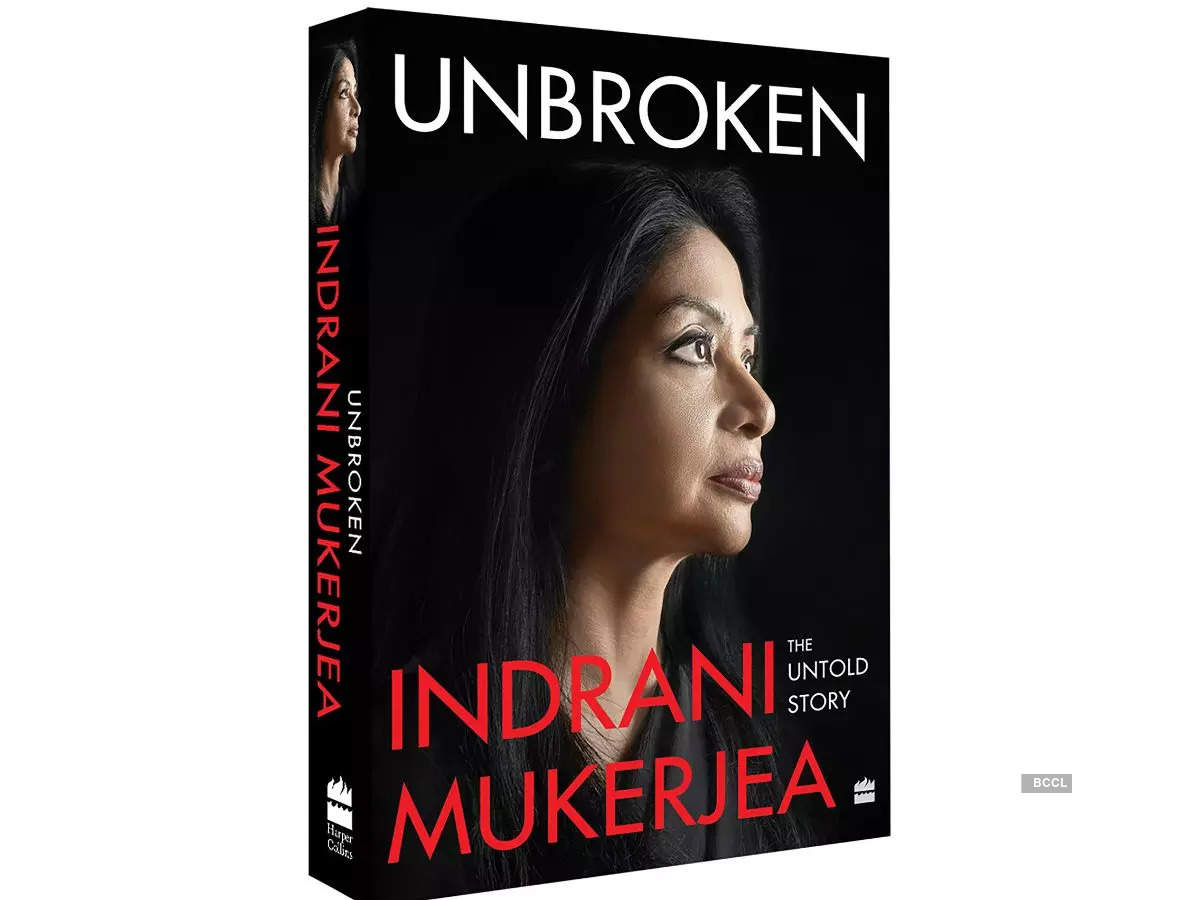

Now, eight years later and out on bail, Indrani Mukerjea tells her story in her own words in a new autobiography 'Unbroken: The Untold Story'. From spending her childhood days in Guwahati, to her rise as a media baron in Mumbai, to spending 2460 days in Byculla jail as prisoner number 1468— Indrani Mukerjea writes about it in her autobiography, which was published on July 30, 2023.

Here's an excerpt from 'Unbroken: The Untold Story' by Indrani Mukerjea, published with permission from HarperCollins India.

In the days leading up to my going to prison, I was in a daze. Things were happening around me and I had no idea how to make any sense of it. It was my lawyer Gunjan who first mentioned the possibility of me having to do some prison time. She said it would last a week, at most.

‘We are doing everything possible to make sure this doesn’t happen. But it looks inevitable,’ she said. I heard the words, yet to understand completely what was going on.

On 7 September, I was handed over to judicial custody. After court, I was taken for the mandatory medical check-up. But, in reality, there are no check-ups—the accused are only made to sign a form when they are taken for a routine check every twenty-four hours to a government hospital. I could have been genuinely sick but no one bothered to check at all.

That evening, I was taken to Byculla Undertrial Jail. The white jeep that used to take me to court was no longer my transport from this day onwards. A blue truck with mesh on the windows was brought out to take me to prison. The cops from Khar police station were seated with me in the truck. It was late in the evening, after the prison bandi (lockdown) that happened at 6 p.m. every day. There were TV channel vehicles and photographers, scrambling to capture every tiny detail of my entry into prison. I was dressed in a pista-green salwar kameez with a dupatta.

My first memory of prison is the small door that takes you in. My head was covered with the dupatta as I entered. Prisoners have to always stoop when they walk in through that door—in a way, you have to bow your head to the supreme law of the land when you walk into jail. There was a bevy of cops inside. Perhaps, the cops accompanying me noticed how I had stiffened; a constable next to me reassuringly said, ‘Dariye matt, kuch nahi hoga (Don’t worry, nothing will happen).’

I was taken straight to the office to sign documents. And from there, I was taken to the jharti (frisking) room. It was probably the most traumatizing part of being in prison.

‘Take off your pants,’ said the officer.

I took off my pants. ‘Your knickers, too,’ she said.

The first time you are taken to prison, you are stripped completely naked. The Police Inspector—PI—from Khar station was there, along with a jailer and female constable. I was in the company of an all-women team. And still, this felt like I was being stripped of my dignity, one piece of clothing at a time. It was scary.

They thoroughly checked my entire body for bruise marks. It was done to ensure that I wasn’t assaulted at the police station. If there was an injury, they wouldn’t have accepted me in the prison, as later this could become a legal issue for the prison authorities. The Khar cop was made to step out before they asked me, ‘Did they hit you in prison?’

They hadn’t. And I said so truthfully.

I was taken inside the frisking room again. During the second round of checking, they again pulled down my salwar to check for cash, drugs, or any other items. I had been told prior to coming to the station that I couldn’t carry cash. Prisoners habitually bring in titbits of personal belongings hidden in their salwar. Frankly, the prison has everything—from kajal to hair dye, so one does not need to bring anything from outside. In the years to come, my hair dye would become a special topic of discussion.

Thankfully, over the years, I regained my sense of humour and would even laugh with my lawyer about it. ‘Very soon, it would be in the supplementary chargesheet,’ I’d tell her.

After all, my chargesheet did have the accusation that I was an ambitious woman. Why should my jet-black hair and some hair dye product lose out on its moment of fame?

READ MORE: