The republication of caricatures depicting the Prophet Muhammad by French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in September 2020 led to protests in several Muslim-majority countries. It also resulted in disturbing acts of violence: In the weeks that followed, two people were stabbed near the former headquarters of the magazine and a teacher was beheaded after he showed the cartoons during a classroom lesson.

Visual depiction of Muhammad is a sensitive issue for a number of reasons: Islam’s early stance against idolatry led to a general disapproval for images of living beings throughout Islamic history. Muslims seldom produced or circulated images of Muhammad or other notable early Muslims. The recent caricatures have offended many Muslims around the world.

This focus on the reactions to the images of Muhammad drowns out an important question: How did Muslims imagine him for centuries in the near total absence of icons and images?

Picturing Muhammad without images

In my courses on early Islam and the life of Muhammad, I teach to the amazement of my students that there are few pre-modern historical figures that we know more about than we do about Muhammad.

The respect and devotion that the first generations of Muslims accorded to him led to an abundance of textual materials that provided rich details about every aspect of his life.

The prophet’s earliest surviving biography, written a century after his death, runs into hundreds of pages in English. His final 10 years are so well-documented that some episodes of his life during this period can be tracked day by day.

Even more detailed are books from the early Islamic period dedicated specifically to the description of Muhammad’s body, character and manners. From a very popular ninth-century book on the subject titled “Shama'il al-Muhammadiyya” or The Sublime Qualities of Muhammad, Muslims learned everything from Muhammad’s height and body hair to his sleep habits, clothing preferences and favorite food.

No single piece of information was seen too mundane or irrelevant when it concerned the prophet. The way he walked and sat is recorded in this book alongside the approximate amount of white hair on his temples in old age.

These meticulous textual descriptions have functioned for Muslims throughout centuries as an alternative for visual representations.

Most Muslims pictured Muhammad as described by his cousin and son-in-law Ali in a famous passage contained in the Shama'il al-Muhammadiyya: a broad-shouldered man of medium height, with black, wavy hair and a rosy complexion, walking with a slight downward lean. The second half of the description focused on his character: a humble man that inspired awe and respect in everyone that met him.

Textual portraits of Muhammad

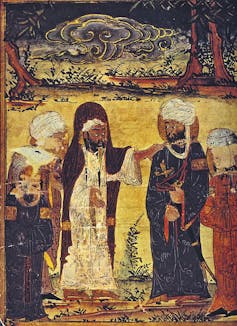

That said, figurative portrayals of Muhammad were not entirely unheard of in the Islamic world. In fact, manuscripts from the 13th century onward did contain scenes from the prophet’s life, showing him in full figure initially and with a veiled face later on.

The majority of Muslims, however, would not have access to the manuscripts that contained these images of the prophet. For those who wanted to visualize Muhammad, there were nonpictorial, textual alternatives.

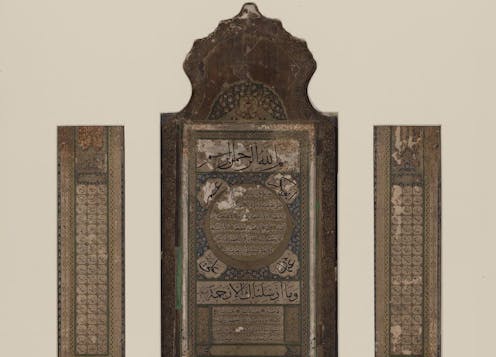

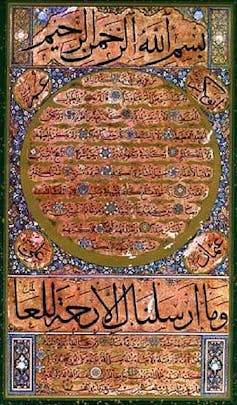

There was an artistic tradition that was particularly popular among Turkish- and Persian-speaking Muslims.

Ornamented and gilded edgings on a single page were filled with a masterfully calligraphed text of Muhammad’s description by Ali in the Shama'il. The center of the page featured a famous verse from the Quran: “We only sent you (Muhammad) as a mercy to the worlds.”

These textual portraits, called “hilya” in Arabic, were the closest that one would get to an “image” of Muhammad in most of the Muslim world. Some hilyas were strictly without any figural representation, while others contained a drawing of the Kaaba, the holy shrine in Mecca, or a rose that symbolized the beauty of the prophet.

Framed hilyas graced mosques and private houses well into the 20th century. Smaller specimens were carried in bottles or the pockets of those who believed in the spiritual power of the prophet’s description for good health and against evil. Hilyas kept the memory of Muhammad fresh for those who wanted to imagine him from mere words.

Different interpretations

The Islamic legal basis for banning images, including Muhammad’s, is less than straightforward and there are variations across denominations and legal schools.

It appears, for instance, that Shiite communities have been more accepting of visual representations for devotional purposes than Sunni ones. Pictures of Muhammad, Ali and other family members of the prophet have some circulation in the popular religious culture of Shiite-majority countries, such as Iran. Sunni Islam, on the other hand, has largely shunned religious iconography.

Outside the Islamic world, Muhammad was regularly fictionalized in literature and was depicted in images in medieval and early modern Christendom. But this was often in less than sympathetic forms. Dante’s “Inferno,” most famously, had the prophet and Ali suffering in hell, and the scene inspired many drawings.

These depictions, however, hardly ever received any attention from the Muslim world, as they were produced for and consumed within the Christian world.

Offensive caricatures and colonial past

Providing historical precedents for the visual depictions of Muhammad adds much-needed nuance to a complex and potentially incendiary issue, but it helps explain only part of the picture.

Equally important for understanding the reactions to the images of Muhammad are developments from more recent history. Europe now has a large Muslim minority, and fictionalized depictions of Muhammad, visual or otherwise, do not go unnoticed.

With advances in mass communication and social media, the spread of the images is swift, and so is the mobilization for reactions to them.

Most importantly, many Muslims find the caricatures offensive for its Islamophobic content. Some of the caricatures draw a coarse equation of Islam with violence or debauchery through Muhammad’s image, a pervasive theme in the colonial European scholarship on Muhammad.

Anthropologist Saba Mahmood has argued that such depictions can cause “moral injury” for Muslims, an emotional pain due to the special relation that they have with the prophet. Political scientist Andrew March sees the caricatures as “a political act” that could cause harm to the efforts of creating a “public space where Muslims feel safe, valued, and equal.”

Even without images, Muslims have cultivated a vivid mental picture of Muhammad, not just of his appearance but of his entire persona. The crudeness of some of the caricatures of Muhammad is worth a moment of thought.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation’s email newsletter.]

Suleyman Dost does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.