What if I told you that your children might live in houses made of mushrooms? Perhaps you might think I had eaten one mushroom too many. But this is no fairy tale. Mushrooms — or more specifically, the mycelium network of underground roots and fibers that feed up to the sprouted stem and cap of the mushroom fruit — will be a crucial tool for humans as we seek to create better, more sustainable, and more adaptable materials with which to build our futures.

“These materials are five times stronger than petroleum-based products, such as polystyrene; grow on agricultural waste with low carbon inputs; have a minimal environmental impact; and are fully biodegradable,” explains Tien Huynh, an associate professor in the School of Science at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Australia. Huynh has extensive experience researching fungi and mycelia and their roles inside our bodies and as part of the wider ecosystem.

Mycelium is made of microfilaments called hyphae, which take in nutrients to feed the mushroom. It is remarkably resilient, can be grown in extreme conditions, and can take on different properties to make it an ideal material for a host of applications, Huynh says. It can even solve complex routing problems and cover vast distances (the largest network spans more than 2,385 acres). But the promise of this natural wonder material comes with its own challenges, too.

“It’s a living organism,” Huynh says. “It’s prone to contamination, and a lot of experimentation is needed to perfect the final product.”

But despite the challenges, it has become increasingly clear in the last 10 years that fungal networks have the potential to shape the future of architecture, fashion, and even consumer electronics.

Still think I’m tripping? Here are three ways mushrooms are being used to push the boundaries of design and function.

3. Towers of toadstools: Mushroom architecture

Mushrooms are mighty — and sometimes huge — structures. That’s a power that we can harness. In fact, mushroom bricks are among the most promising green building materials we know of because they’re relatively cheap and easy to make, can be implemented into all kinds of construction projects, and are much more sustainable than traditional building materials.

To make a mushroom brick, you don’t need cement, expensive equipment, or vast amounts of heat. Instead, you fill a mold with some agricultural waste, a little sawdust or straw, and add mushroom spores. Mycelium acts as a natural binder, thus transforming the organic matter into a light, durable, biodegradable brick in a matter of days.

Huynh says engineers can manipulate the mycelium in the early stages of growth to give it more desirable properties.

“We have added things to either the substrate or as additives that improve fire resistance,” she says.

Some innovative projects aim to create new structures from mycelium and use old construction materials to grow them. Biocycler, for example, is a portable container that uses fungi to process waste, removes harmful substances like chemicals and varnish, and produces new mycelium bricks.

The need for new, sustainable building materials is urgent. About 39 percent of global carbon emissions comes from the energy needed to build and maintain buildings, according to the World Green Building Council. Because mycelium bricks are organic and biodegradable, they are ideal for temporary structures like art installations or shelters. Ecovative, one of the leading mycelium design companies, has even received funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to develop simple buildings made from mycelium for military or humanitarian purposes.

Where mushrooms could really make the difference is in building habitats far from home.

The theory goes that small and light samples of dormant fungi spores could easily be transported on a long journey to the Moon. Once the astronauts arrive, they could add water and nutrients to the spores and introduce them to a framework, essentially cultivating a thermally regulated, fire-resistant habitat in-situ.

A paper published by NASA also suggests that living mycelium habitats may function as “a living shell,” which sounds a little like the set for a sci-fi sequel to Jim Henson’s Labyrinth but is in reality a structure that would have the ability to regulate its own humidity and heal itself.

“Right now, traditional habitat designs for Mars are like a turtle — carrying our homes with us on our backs — a reliable plan, but with huge energy costs,” says Lynn Rothschild, the principal investigator on the myco-architecture project from NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley. “Instead, we can harness mycelia to grow these habitats ourselves when we get there.”

2. Moda Mycelia: Fungi fashion

Leather alternatives are not new. But unless you love the squeaky, clingy, sweaty feel of pleather enough to not care about the fact that it is also environmentally damaging to produce and not biodegradable, then you might want to consider mycelium leather instead. As soft and supple as the real thing, mycelium leather has made it into a pair of Adidas sneakers in the form of Mylo, a product of Bolt Threads. In case you can’t tell, Mylo was used to make the outer upper, heel tab overlay, and Adidas branding on the shoes.

The process Bolt Threads uses to grow Mylo is similar to brick-making. Mycelium is seeded onto a base layer, forming a 3D mat — a big, foamy doormat, if you will. The strain of mycelium Bolt Threads uses to make Mylo forms a particularly dense network, which is good for durability. After the material forms, it is purified and dried to be sent to a processing plant to create the look and feel of leather.

Mylo has been used by various fashion brands: Lululemon made a yoga mat and bags out of it, while Stella McCartney has made clothing and accessories, including the Frayme Mylo bag. Another company, MycoWorks, created a mycelium leather bag for Hermès in 2021, called Silvania. Car maker Kia also teamed up with South Korean startup Mycel to develop mycelium-based materials to replace traditional leather for the interiors of its cars.

Opting for the mycelium leather seats over regular cowhide leather makes business sense: It doesn’t decay as fast as animal leather, doesn’t require much energy or space as a cow to produce, “feeds” on waste, requires no toxic chemical processing to look good, and (depending on the kind) can biodegrade in your garden once you’re done with it.

According to the Boston University School of Public Health, every year people in the United States throw away more than 34 billion pounds of clothes — roughly 100 pounds per person. For context, a winter coat might weigh 5 pounds, so that is equivalent to 50 winter coats going to the garbage every year. We really love fast — disposable — fashion.

Huantian Cao, a professor and co-director of the Sustainable Apparel Initiative at the University of Delaware, believes mycelium is a solution to at least one of those characteristics.

“If mycelium composites are used as shoe soles, for example, consumers can just throw the shoe soles into their backyard after using them, and they will be biodegraded,” he explains. Unfortunately, Cao says, the fast part is less easy to fix: Mycelium takes a while to grow in the quantity needed to produce a bag, never mind an entire Macy’s store worth of bags.

A 2021 study in the journal Resources, Conservation, and Recycling even proposes combining two waste problems in one: Make fungal sheets from bread waste and you can make mycelium leather.

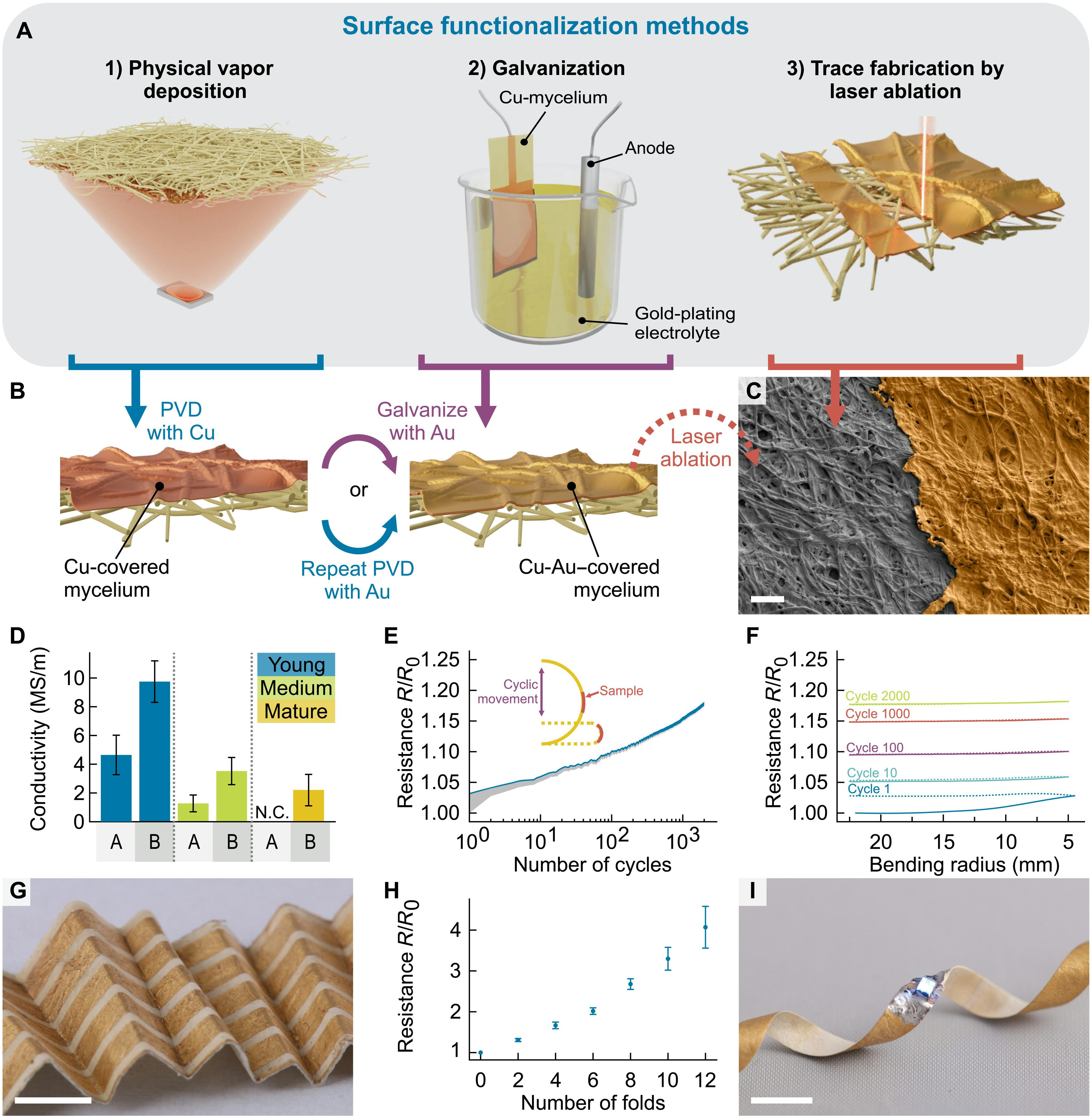

1. Mycelium motherboard: Electronic technology

OK, so you can’t switch a computer for a mushroom brick. But “soft” electronics — the kind woven into wearables, for example — may be made better by using biodegradable, heat-resistant, flexible, endlessly customizable mycelium.

A 2022 paper introduces a range of myceliotronic concepts that all work by creating a kind of mycelium skin, which is engineered into devices. To make this fine film of fungus, the researchers put Ganoderma lucidum spores (that’s reishi) into wood. They controlled the conditions so the fungus could grow but not produce mushrooms, so it was incredibly smooth. They then harvested a thin outer layer of the mycelium and dried it.

Once dry, these skins can withstand temperatures up to 482 Fahrenheit and 2000 “bending cycles” (another way of saying they’re incredibly flexible) and replace standard circuit boards and even battery parts, which are usually made from nonrecyclable materials or plastics.

Another paper suggests that mycelium could also be used to produce sustainable textiles that act as wearable sensors, like smart clothing. The research team colonized fabric with fungus spores that reacted to light, temperature and moisture, as well as environmental chemicals. This suggests that these fabrics may have the potential to act as simple sensors.

Tired: Fitbit. Wired: FungusBit.

Cao believes that mycelium’s true potential is in creating luxurious and highly desirable devices, clothes, and homes. But if The Devil Wears Prada taught us anything, it is that today’s fashion week runway look is next year’s bargain bin outfit. Mushroom-made bricks and textiles might be as luxurious and expensive as a white truffle, but we’re willing to take the bet that within the next 10 years, mycelia will help build our futures — on and off Earth.