On Sunday 19 March 2000 Mubarek Amin visited his son, Zahid, in Feltham young offenders’ institution. Zahid was 19 and in the final days of a 90-day sentence for stealing a packet of razor blades – it was his first criminal conviction.

Mubarek asked his son how he was coping with life behind bars. Zahid assured him he had learned his lesson. He said he wanted to change his life around and he couldn’t wait to leave Feltham behind. He also mentioned that his cell-mate, Robert Stewart, who had the letters RIP tattooed on his forehead, had been acting strangely: he would stare at Zahid for hours on end without saying a word. It was a little unnerving. Zahid was due to be released on the Tuesday and his father would be collecting him. “I’m coming out at 8am,” Zahid told his father. “Make sure you’re not late.” They were the last words his father would hear his son speak. Two days later, only hours before he was to be freed, Zahid was bludgeoned to death by Stewart.

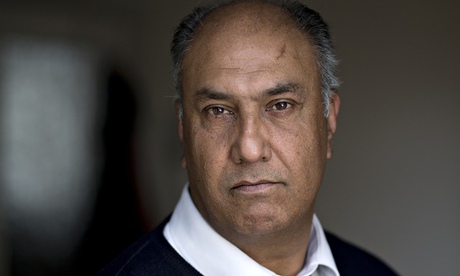

Mubarek Amin opens the door of his north-east London home and leads me into the living room. He has lived on this street in Walthamstow since he arrived from Pakistan in 1968 when he was eight. In the 15 years since Zahid’s murder, there have been reports and inquiries. Ten years ago, the killing inspired a stage play, Gladiator Games, and it is now the subject of a new British feature film, We Are Monster. This is the first time Mubarek has agreed to talk about his son. “I haven’t talked about it before because talking brings back so many memories,” he says.

On the morning Zahid was due to be released, the door bell rang at 6am.

Amin opened the door to a policeman who told him his son had been involved in an accident. He and his wife accompanied the police to Charing Cross hospital.

They arrived before the ambulance carrying Zahid, who had first been taken to a hospital that was equipped to deal with head injuries. Amin assumed that his son had been involved in a minor incident at Feltham but when the ambulance arrived and he saw Zahid lying on the trolley bed, he was confronted by his boy’s terrible injuries. “I looked at him, his head, and it was swollen, bruised, bashed,” he says. “He was unconscious. I said to the doctor, what chance does he have? The doctor said it was looking very bad.” Amin sat in the corner of a hospital waiting room and broke down.

Zahid was in hospital for a week connected to nine machines that kept him alive. The family were with him round the clock. “I was scared, I was falling to pieces,” recalls Amin. “All I wanted was for him to get better – which didn’t happen.”

After seven days, the hospital told the family they should consider turning off the machines. Amin said the family would discuss it and sleep on it. They returned home only to receive a phone call. Zahid was dead.

The family rushed to hospital. “I was bawling my eyes out,” Amin recalls. “It felt like I had lost a part of my own body – it was the worst day of my life.”

Grief later turned to anger as the details of what happened emerged. Zahid had been attacked by Stewart with whom he had shared a cell for six weeks. According to the Commission for Racial Equality (now the Equality and Human Rights Commission) report on the murder, one prisoner said of Stewart: “I called him Madman – other prisoners had names for him like ‘Sicko’.”

Stewart was a known racist who had boasted that he would commit the first murder of the millennium. “I am very angry,” Amin says. “Why was he allowed to share a cell with this guy, when it was known he was a racist and trouble-maker?”

Stewart murdered Zahid by clubbing him several times about the head with a wooden table leg. He was charged with murder.

The only time Amin has been face-to-face with Stewart was at the trial. “He walked past us one time and he turned round and just sneered at me,” says Amin. “The whole family was just in disbelief.”

Stewart was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. “He got 18 years, which was a life sentence, so he is going to be out in three years,” Amin says. How does that make him feel? There is a long pause. “It’s not good, is it?”

What would he say to him if he were to see his son’s killer? “I’m not really sure what I would say to him. But I know I would like to get my hands around his neck.”

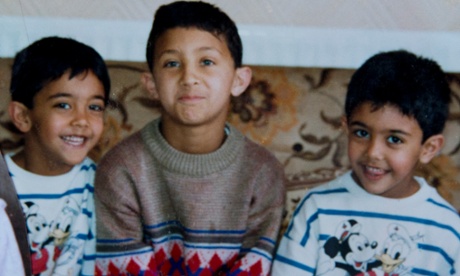

Zahid did not look like a typical Pakistani boy. His hair was brown not black, his skin was fair and his eyes were green. Those differences, inherited from his mother, seemed innocent as a child but once he started school, they brought him unwanted attention. The other Pakistani boys would mock and bully him, and he often got into fights. Amin thought that was the full extent of it, but the inquiry into Zahid’s murder would suggest that by his teens, he had started to dabble in petty crime. The inquiry heard that he had a number of brushes with the law – possessing an imitation firearm with intent to cause fear of violence, shoplifting and interfering with a motor vehicle in an attempt to remove audio equipment.

Zahid kept his troubles – including alleged drug addiction – secret. “We found out later that when he got into trouble with the police he would give the address of a friend so the letters would not arrive at my house,” says Amin. “Or he would get up first thing in the morning and get the letters before us – when boys get into trouble, the last thing they want to do is tell their dad.”

On 17 January 2000, Zahid was sent to Feltham after being found guilty of stealing razors and interfering with a motor vehicle. Rather than being angry, Amin was at first shocked but then rather relieved his son was going to prison. “I thought he was hanging out with the wrong crowd and that the 90 days would do him good,” he says. “It would wake him up – I imagined prisons as places where you have classrooms with teachers showing you how to face up to the way you have behaved.”

Each weekend, Amin visited his son and when they talked, it sounded as if prison was doing its job. “He would say, ‘this is not the place I want to be,’” Amin says. “He told me, ‘I want to get out of here and sort my life out.’”

Zahid talked about joining the army. When he mentioned that his cell-mate was behaving strangely, his father told him: “Just keep your head down and ignore him, you’ll be out of here soon.”

We Are Monster recreates the last days of Zahid Mubarek’s life. The film-makers approached the family about the idea. Amin says the family have often been approached with ideas for dramas that came to nothing. There was no reason to believe this time would be different, but writer Leeshon Alexander, who also plays Stewart, and director Antony Petrou surprised them by securing the funding and making the film. The family were invited to a screening. “I was in the cinema, but I didn’t watch most of the film,” Amin says.

“It brought back too many memories, so I had my head turned away from the screen.”

He’s not sorry that the film was made, because it is a way to ensure that the errors that led to Zahid’s death are recalled and it also helps bring attention to the Zahid Mubarek Trust, a charity set up by his family to campaign for reforms and challenge discrimination within the criminal justice system.

“The film is good for the campaign,” Amin says, “but it’s not good for the family.” An official inquiry into the death of Zahid Mubarek was published in 2006 and it found 186 failings that led to his death. It also found there was a casual disregard towards racism at Feltham. Stewart had severe personality problems but he was never inspected by a doctor at Feltham. He attacked Zahid with part of a table leg that he had broken away from furniture in their shared cell. The fact that this was not spotted by officers was part of a widespread problem of poor inspections and management of dangerous prisoners. The chief inspector of prisons claimed last year that a murder like that of Zahid could happen again because since his murder the drive for reform has been weakened or forgotten.

“The last 15 years have gone by slowly,” says Zahid’s father. “People say things get better over time, but for us it is like all this happened yesterday.”

Zahid is not forgotten but Amin does not like to dwell on the past. Is he frightened that by thinking about the past the pain will overwhelm him? He nods. “It is a coping mechanism,” he says. “I don’t want to deal with it because it is so painful.” The only thing that helps to alleviate the loss and the pain is his faith. “I am a Muslim so I do think I will see him again in the next life,” he says. “It helps to believe that one day I will see my son again. Inshallah.”

• For more information on the Zahid Mubarek Trust visit thezmt.org. We Are Monster is in cinemas now and released on DVD on 11 May