How Graham Reynolds became Texas’ top composer.

by Rose Cahalan

October 14, 2019

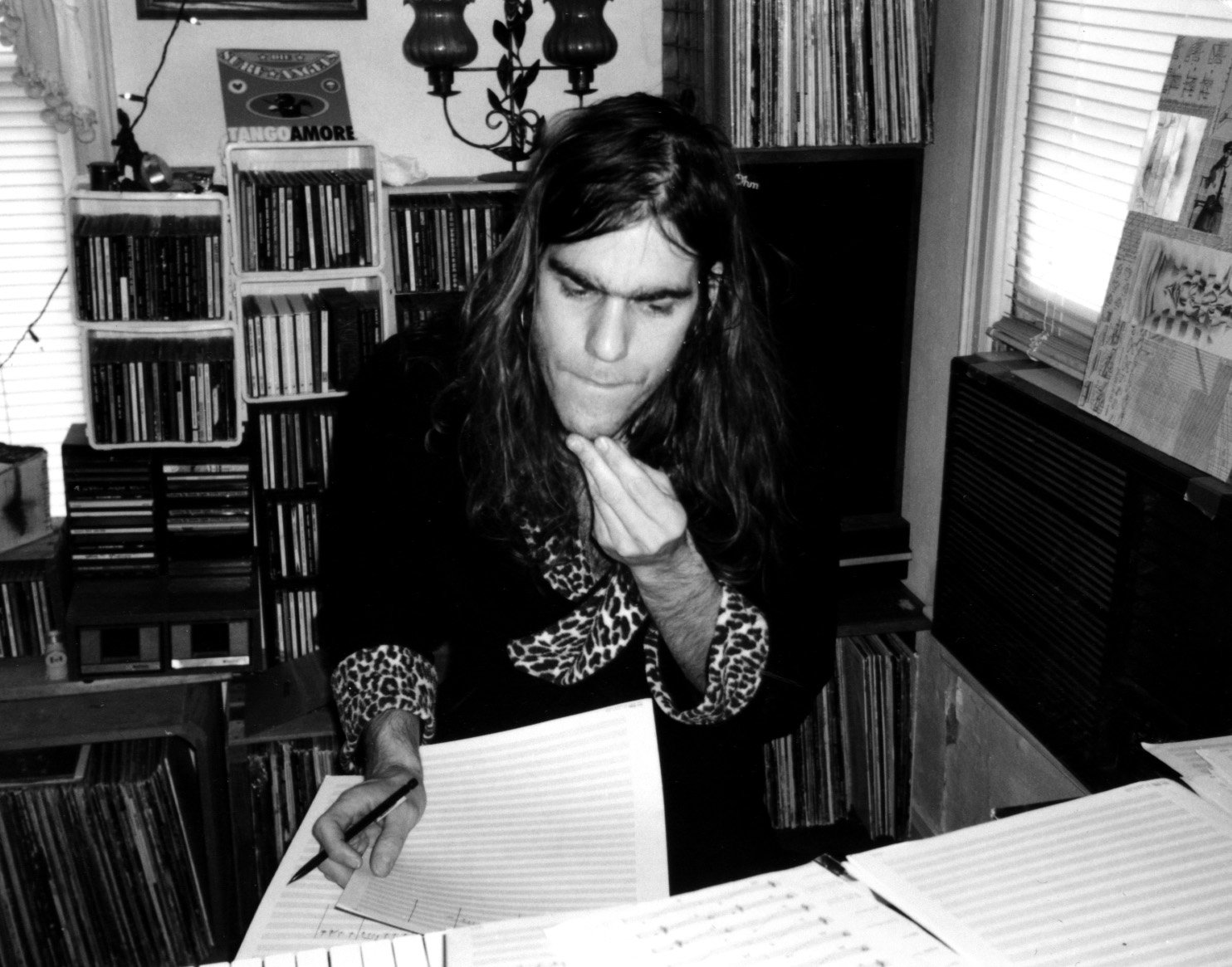

Walk into composer Graham Reynolds’ East Austin studio, and the first thing you’ll notice, perhaps surprisingly, is the books. There are two whole walls of them: floor-to-ceiling shelves filled with hundreds of music books, naturally, but also cookbooks and novels, comics and zines, science fiction and history. On the stifling July afternoon when I visited, a coffee table was crowded with the work of Maria Sibylla Merian, a German entomologist and illustrator who lived during the late 1600s. Merian, one of the first scientists to directly observe and document butterfly metamorphosis, was a pioneer in an era when insects were commonly described as “beasts of the devil.” Reynolds is reading everything he can find about her, he says, as part of his research for a potential new project, something he’s calling “an insect opera.”

What does that even sound like? Reynolds wonders the same thing, but an eclectic project like this would be perfectly in character for the 48-year-old. Though he’s a vegan, his musical appetite might best be described as omnivorous. Reynolds makes music with dance companies, symphonies, filmmakers, actors, artists, and scientists in genres including but not limited to classical, jazz, electronic, punk, and noise. He’s scored compositions for a vast array of projects, from the movie Bernie to a dance performed in Kyoto by members of the Japan Women’s Baseball League. His latest score is for the film adaptation of the novel Where’d You Go, Bernadette. He has twice destroyed a piano with a sledgehammer in front of an audience.

“Graham can do everything,” says Stephen Mills, artistic director of Ballet Austin and a frequent collaborator. “His music can be as romantic and heartbreaking as anything you’ve ever heard, and on the other end of the spectrum, it can be so abstract and dark. … Good art only comes out of curiosity, and he is an exceedingly curious person.”

Paola Prestini, a composer in New York City who’s worked with Reynolds, says he’s one of only a handful of classical composers who have found success in numerous media. “There’s just not a lot of people working fluidly across all these fields,” she says. “He certainly falls in the top echelon of great artists right now.”

Reynolds’ quirky, multidisciplinary career also offers a compelling example of what it means to be a nationally recognized professional composer in 2019. The conventional story involves training at a top conservatory, then moving to New York City or another coastal metropolis, often compromising one’s own idiosyncratic taste in favor of what will sell. Reynolds has done none of these things over his 26-year career. Yet he’s become not just an in-demand collaborator, but also a thriving entrepreneur who employs four people and founded a nonprofit meant to equip young composers with resources that didn’t exist when he was starting out. He’s living proof that sometimes, choosing to stay weird—and stay in Texas—does pay off.

Reynolds grew up amid noise. His mother ran a day care out of their home in Bethany, Connecticut, and he describes the environment as a kind of barely controlled chaos. “There’d be a marching band down the hall, with kids banging on instruments while you’re trying to sleep,” he says. “I had a crib in my room and changed more diapers than anybody.” When his mom, Dona, started taking piano lessons and practicing at home, 5-year-old Reynolds and his younger brother, Keith, asked for lessons, too. Reynolds’ father made a modest salary as a high school history teacher, and the family couldn’t afford three sets of lessons, so Dona quit and the boys kept going. Though they’d both end up in artistic jobs—Keith went on to write musicals—neither was a prodigy, and their interest waxed and waned. “The rule was, we had to practice 15 minutes a day,” Reynolds recalls, “which was smart on my parents’ part. There were some years where you’re like, ‘Eh, I don’t want to play piano anymore.’ But 15 minutes in the morning before school was easy. And by the end of that 15 minutes, I’d usually be playing my own stuff.”

Reynolds credits his choice of career to a string of outstanding music teachers. “That was the bottom line,” he says, “because if I’d had an amazing series of science teachers, I probably would’ve become a scientist. I was always most interested in whatever the best teacher that year was teaching.” An elementary school teacher named Mr. Diamond passed out handmade guitars, keyboards, and congas to each member of the class; he also hosted a piano club in which the kids learned to read chord symbols. Learning chords and basic music theory “opened up the world,” Reynolds says. “And that led to improvisation and composition.”

He started hanging around the local record store, spending his allowance on obscure albums from the $1 bin. A high school jazz teacher, Mr. Hickerson, encouraged him to write his own songs, including for a series of school concerts that featured students’ original music.

By the time Reynolds started college in 1989, he was fascinated by classical, rock, jazz, and punk, as well as global sounds like Indonesian gamelan and African drumming. Though he was already set on a music career, he majored in Latin American history at Connecticut College. “I didn’t like the music department there,” he says. “I didn’t really like the music department anywhere. There was not an obvious place to go to learn to make the kind of music I wanted to make.” The punk scene, with its DIY, anything-goes aesthetic, felt the most welcoming. Reynolds played drums in “a million bands” and frequented punk clubs, especially the Anthrax in Norwalk, Connecticut—all while just scraping by in his Spanish classes.

He moved to Austin in 1993, having heard it was cheap and had a lively music scene. Paying $230 per month for a bedroom in South Austin, Reynolds took a job cleaning houses and with a few friends formed a band in which he played keyboard and drums. They were a staple at small clubs like Hole in the Wall, Flamingo Cantina, and, most frequently, Emo’s. Though the band was named Golden Arm Trio, it was a trio only in the loosest sense: “Our very first gig at Emo’s was three people, but the saxophone stormed off at the end of the night and then we were two for a while,” he says. Golden Arm Trio still performs, with Reynolds as the only permanent member among a rotating cast. He now uses the band as a vehicle to experiment with new music; a song first heard at a Golden Arm Trio show may later end up in a film or dance performance.

Listen to Reynolds’ music as you read.

Peter Stopschinski, a friend and fellow composer, remembers Reynolds as meticulous and ambitious even in those early years. “He was always willing to do extra things,” Stopschinski says. “Most musicians just want to fuck with the music. Graham and I, we wanted to write a symphony, then draw the poster and choose the font.”

Imagining himself more as a performer than a songwriter, Reynolds says he stumbled into composing: “Friends started asking me to score their things, whether it was a puppet show or an experimental film, and I just kept saying yes.” Over about 10 years, he was able to slowly cut back at his housecleaning job, working five days a week, then four, then three, then none. “I didn’t really have a backup plan,” he says. “I never questioned whether I could make music my living.”

In Austin today, where the cost of living continues to rise faster than in almost any other U.S. city, most young artists don’t have that privilege—a change that Reynolds says pains him. “There are large parts of the arts and music community that you see either threatened or dying or both,” he says. “And there are others that I see thriving … but we need more resources, especially for emerging musicians.” Reynolds teaches at the Austin Chamber Music Center’s Young Artists Academy. His nonprofit, Golden Hornet, also hosts an annual young composers’ concert and the String Quartet Smackdown, a bracket-style tournament for new composers. Fellow musician Prestini, who runs a similar, larger venture called National Sawdust, says that opportunities like these are sorely needed: “Especially as a woman, starting out as a composer, there was very little out there for me.”

A single violin plays a slow, sad melody in a minor key, dripping with vibrato. Then distorted electronic sounds join in, as well as a skittering, creepy metallic noise that suggests swarming cicadas. “Seven years from now—Anaheim, California,” reads flickering yellow text on a black background. Cut to a man furiously scratching his hair as tiny green bugs crawl over him. When he steps into the shower to try to wash them away, a deeply unnerving yet downright funky electric bass line begins. With the uncanny music as a cue, it’s clear that these bugs aren’t real, but rather a hallucination. You can’t look away; you’re also fearful of what’s to come. The opening credits of A Scanner Darkly haven’t even finished, and already Reynolds’ music has viewers hooked.

This 2006 movie, directed by Richard Linklater and adapted from a novel by Philip K. Dick, was a modest indie success—and it was also Reynolds’ big break. The movie stars Keanu Reeves as an undercover cop whose job is to catch dealers of Substance D, a highly addictive hallucinogenic drug that’s sweeping the country. Reeves’ character soon gets hooked himself and is entangled in a web of lies and paranoia. It’s dark stuff, to be sure, but the cult classic is leavened with Linklater’s trademark ingredient: dialogue that’s long, meandering, funny, and engrossing. Scanner was one of the first feature films made using rotoscoping, in which animators trace over live-action footage to produce a surreal, shaky visual style. Reynolds cleverly echoed that technique in his score, layering distorted electronics on top of piano and strings. Cinema Retro magazine named it “Best Soundtrack of the Decade.”

After Scanner, Reynolds says, “a lot more doors opened.” His partnership with Linklater spans genres from romance (Before Midnight, 2013) to drama (Last Flag Flying, 2017) to dark comedy (Bernie, 2011, and Where’d You Go, Bernadette, 2019). Each score requires hundreds of hours of work, from reading the screenplay and other source material to endlessly exchanging edits with the production team. Scenes often get left on the cutting-room floor, which means writing new songs on short notice or letting go of beloved ones that no longer fit. Flexibility and a lack of ego are key.

Composing for Hollywood is lucrative, and Reynolds could have easily decamped to Los Angeles and focused only on film. Instead, he’s continued to juggle a variety of Texas-focused projects. Among these is Grimm Tales, a Gothic retelling of classic fairy tales performed this spring by Ballet Austin. (This is not a Disney-fied version of storybook tales. In one piece, “The Juniper Tree,” an evil stepmother beheads her stepson, bakes him in a pie, and serves it to his father; the boy is reborn as a bird and drops a millstone on the stepmother’s head, killing her.) Reynolds’ catchy, creepy score veers wildly between gentle strings and bombastic noise, and as the dancers perform in front of artist Natalie Frank’s twisted paintings, the ballet expands into a true multimedia experience. “I think of everything I’ve done, Grimm got the closest to synthesizing all my skills,” Reynolds says. “It was a 20-piece live ensemble, but with a lot of electronic stuff, prerecorded stuff, and loops. Really, really fun.” The show received rave reviews.

Reynolds also stayed close to home for last year’s Pancho Villa From a Safe Distance, a bilingual cross-border opera about the legendary Mexican general. First performed in Marfa, the opera is now touring nationally.

Nick Montopoli, a violinist and member of Reynolds’ production team, admires that his boss and friend has chosen to stick around. “You’d think of those as two separate paths—big-time film composer and staple of the local community—but he’s managed to do both,” Montopoli says. “That’s rare.”

As night settles over Givens Park in East Austin, gleaming cars with swangas—those shiny metal rims that protrude from the wheel—cruise through the parking lot, drivers and passengers talking through rolled-down windows. A game of pickup basketball has just ended, and a vendor at a tent advertising “chicken wangs for sale” is packing up. But the party at Givens Pool is only getting started.

It’s the debut of “Givens Swims,” an unusual dance performance starring lifeguards, pool regulars, and maintenance workers. Twenty minutes before the show, the bleachers overlooking the pool are packed, people chatting as Earth, Wind & Fire’s “September” plays over the speakers. At the front desk, a teenage lifeguard uses his flotation device as an air saxophone. Reynolds, who will play keyboard and lead an eight-piece band in performing his score, is holding court by the shallow end, talking to crew members and wearing a suit jacket despite the 90-degree heat. He’s written the music for almost every project by Forklift Danceworks, director Allison Orr’s nonprofit, which creates dances by and for working-class people. Forklift dances have featured sanitation workers, college cafeteria chefs and electric linemen. The conclusion of a three-year series, “Givens Swims” aims to draw attention to Austin’s underfunded, aging, leaky city pools, the most dilapidated of which are in majority-black and Latinx neighborhoods. Givens was only the second public pool for East Austin’s black community when it opened in 1958; the city’s pools remained segregated until 1963.

Orr finds poetry in daily work. You wouldn’t think a simple pH test could be dramatic, but when performed in unison by five maintenance men, who are dramatically lit as they lie next to the pool, fill beakers with water, and hold them up to the light, it’s oddly moving. Later, a propulsive, urgent trombone line is paired with a recording of a worker explaining what poor shape the 61-year-old pool is in: “It’s a struggle every day … it’s at the end.”

The evening’s highlight, though, is a dance starring former winners of the Miss East Austin beauty pageant, part of which took place at Givens Pool. Now in their 60s and 70s, the women are resplendent in gowns and sparkling tiaras, waving atop floating loungers paraded around the pool by manservants. Their million-watt smiles and a jazzy trumpet solo have the crowd cheering. On the surface, it’s a joyful, catchy number; consider it more deeply, and the piece is about history, race, and gender, honoring Givens Pool as a longtime gathering place for Austin’s black community. To match the nostalgic mood, Reynolds’ composition pays homage to jump blues, a 1940s genre somewhere between blues, jazz, and swing. I’m reminded of something he said earlier. “What I like about Beethoven or Duke Ellington or others who kept exploring,” Reynolds says, “is that they made music that was so rich a person can spend their lifetime studying it, but there almost always was a top layer that was inviting. I try to make something that invites a wide range of people in, and the hope is that there’s a rich layer underneath.”

For now, Reynolds’ white cowboy hat bobs up and down as he nods in time to the music, a curtain of long hair hiding his face.

All the Observer's culture stories, straight to your inbox. Sign up for the culture newsletter:

Read more from the Observer:

-

Who Is John Cornyn Serving?: The senior senator from Texas has mastered the art of political subservience, making him very powerful—and perhaps vulnerable.

-

The Clothes that Make the Man: Jose Villalobos’ art redresses the macho traditions of norteño culture.

-

‘Seadrift’ Dredges Up a Little-Known—and Deeply Disturbing—Texas Story: An electrifying new documentary captures a forgotten conflict in the sleepy coastal community of Seadrift.