In a recent study published in Instrumentation and Methods for Astrophysics, the private space company Rocket Lab outlines a plan to send its high-energy Photon spacecraft to Venus in May 2023 with the primary goal of searching for life within the Venusian atmosphere. The planet Venus has become a recent hot topic in the field of astrobiology, which makes the high-energy Photon mission that much more exciting.

Why is Rocket Lab going to Venus?

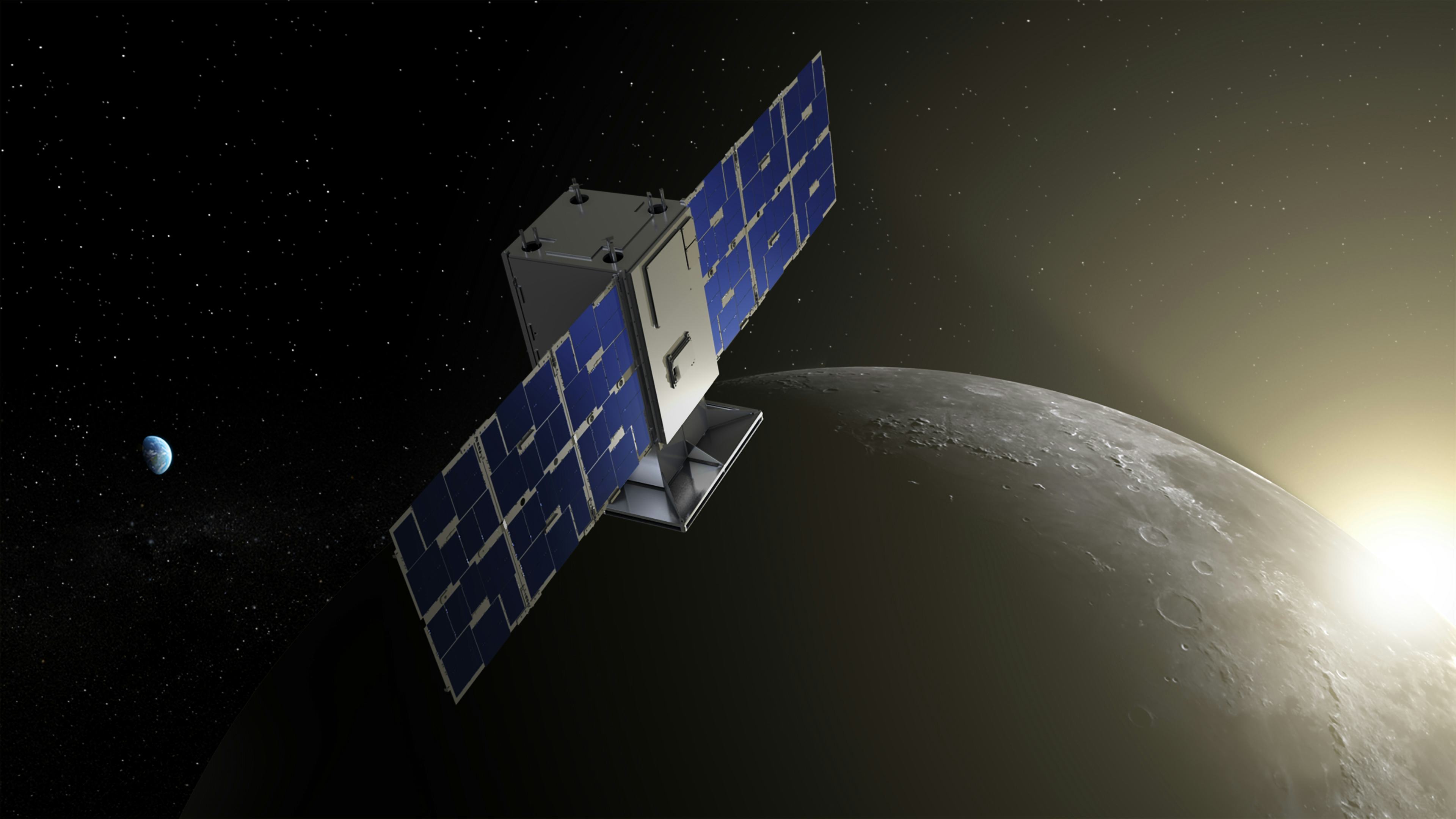

Rocket Lab hopes to build off its recent successful launch of the CAPSTONE mission using its Photon satellite bus, which consists of a CubeSat designed to study the near rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO) around the Moon and its applications for long-term missions such as Gateway.

“With the high delta-V capabilities we just demonstrated on CAPSTONE, we can now access almost every destination in the inner solar system with Photon,” said Richard French, who is the director of business development strategy for the Space Systems Division at Rocket Lab and lead author of the paper.

“What makes Venus compelling to us is that until recently, it hadn’t gotten a lot of attention in terms of missions targeting Venus and, in particular, planning in-situ measurements. With VERITAS and DAVINCI now in implementation by NASA, there is more focus, but with those missions going no earlier than the late 2020s, we hope to increase the rate of discovery by going much sooner.”

VERITAS and DAVINCI+ are two recently approved missions by NASA meant to study Venus more in-depth, including its atmospheric composition and geologic history.

Mission details: Dates, specs

The timeline — Currently, a high-energy Photon appears to be on schedule for a May 2023 launch.

“The development is proceeding as quickly as possible, with an eye towards taking advantage of next May’s launch opportunity,” explains French.

“If we can’t make it, then we have a backup in January 2025. Either way, we are committed to moving as quickly as we can. We are benefiting from a strong partnership with our science team delivering the flight instrument late this summer and a bunch of flight spare hardware from the CAPSTONE mission.”

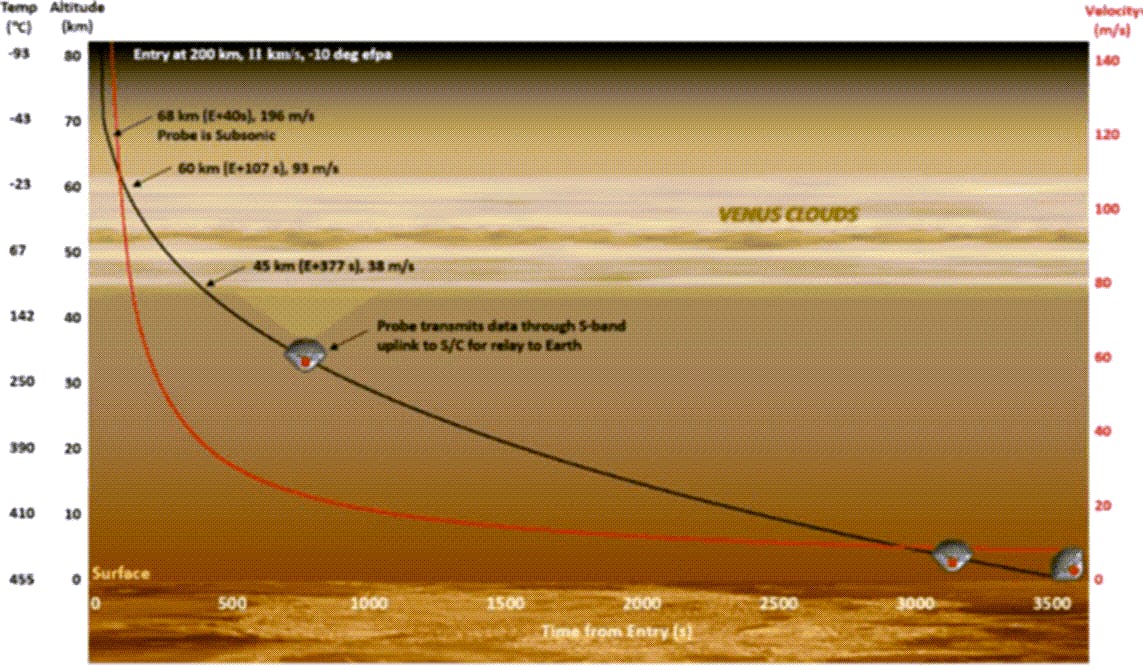

The mission — High-energy Photon will launch onboard Rocket Lab’s Electron launch vehicle while ferrying a small probe with a single ~1-kilogram (2.2-pound) science instrument known as the autofluorescing nephelometer (AFN), which is designed to shine a laser onto cloud particles within Venus’ atmosphere in hopes of causing organic molecules to fluoresce, or light up. One such organic molecule, the amino acid tryptophan, is known to possess fluorescent properties.

The probe is scheduled to spend approximately five minutes in the Venus atmosphere at 48 to 60 kilometers (30 to 37 miles) above the surface, collecting an assortment of data to search for evidence of life.

Since scientific planetary missions have been in the purview of government organizations throughout the Space Age, the high-energy Photon mission to Venus could potentially expand scientific planetary missions from the private sector.

“The ability to send a small payload of one or two instruments at a time enables focused science on rapid timescales and is a game changer for science,” said Sara Seager, a professor of planetary science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the mission’s principal investigator, and a co-author on the paper.

“Missions otherwise typically take years to a decade to plan and implement, making it hard to jump on answering new and exciting science questions.”

The probe will only spend approximately five minutes collecting data within the Venusian atmosphere. Despite this small window, this mission is considered a “first step in a campaign of small missions to better understand Venus,” as noted by the paper.

“We envision two follow-on missions,” explains Seager. “One with a larger Probe with a parachute that can spend an hour in the Venus atmospheric cloud layers. The next is a small balloon mission to last a week or more, inspired by the Russian Vega balloons sent in the 1980s.”

This article was originally published on Universe Today by Laurence Tognetti. Read the original article here.