In an interview with The Paris Review, novelist Don DeLillo said, “I’m completely willing to let language press meaning upon me”. That’s not to say the sound of a sentence should be given priority over its meaning, but that meaning finds its full expression – is discovered – in the aesthetically elegant or stylistically forceful sentence.

This is the feeling one gets reading Robert Dessaix, the 81-year-old Australian novelist, essayist, journalist and memoirist. In his latest book Chameleon, a memoir, Dessaix’s dexterous use of language moves him to insight, self-reflection and remembering.

Review: Chameleon: A Memoir of Art, Travel, Ideas and Love – Robert Dessaix (Text Publishing)

Dessaix writes in the book about his youth, his homosexuality, his adoption, sex, love, travel, art, literature, language, death and faith. There is an approximate chronology, but the book is largely arranged by a mind at play. Dessaix makes use of the strange plasticity of recollection and the flexible possibilities of essayistic writing to happily tolerate ambiguity and contradiction.

Chameleon unspools as memory does: as an ongoing negotiation with the self. It is easy to analogise memory to the process of watching a home video or leafing through a book of photographs (or perhaps, now, scrolling through a digital archive of images and videos). But Dessaix understands memory as a kind of swooping, erratic reverie. He draws connections across decades, tracing the people and places who recur or recede. Their significance is allocated in retrospect.

As a life takes shape, becoming describable and narrativised, the past shimmers and reshapes itself as we try to lock it down. Dessaix accounts for this perpetual uncertainty by parcelling himself out and staging a series of internal conversations.

Reflecting on the long-ago breakdown of his marriage, he writes: “I never had any mates, although I had a few male friends. (Didn’t I? Didn’t you? We must have.)” This is typical of Chameleon’s style: a statement about the past interrupted by a pause for self-reflection that makes space for a vibrant, meaningful hesitancy.

The “you” is Thomas Robert Jones, Dessaix’s much younger self, to whom the book is more or less addressed (“Jones” is the surname of his adoptive parents; “Dessaix” is his birth name). Dessaix describes his addressee as “my long ago Jones self, the self I was given when I was adopted, poised, one delicate foot in front of the other”.

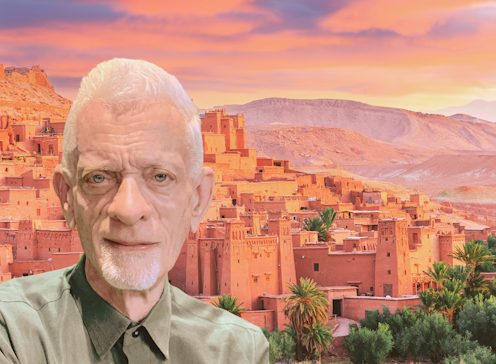

He writes with sensitivity about this past self, adopting the kind of gentle, loving gaze a therapist might encourage in a patient who needs to be more generous to himself. Dessaix explains with care, for example, the kinds of revelations that arrive only as we age: “We needed Morocco to make us innocent, Thomas Robert.” Sometimes he apologises: “Sorry to harp on Stephen Dedalus, especially when you were impervious to Joyce at the time.”

He marvels at how the world can transform over the course of a lifetime: “You’d be astounded how heavily policed our public utterances are today, sixty years later, in the West. As I remember, you hoped for something better.” Dessaix’s point of comparison is the Soviet Union, where he spent time during his twenties.

A narrative foil

There is a third character in Chameleon, a foil for the narrator and his younger self, who helps give shape to memories and arguments. This figure is Dessaix’s friend Niall, whom he describes to Thomas Robert:

You never met Niall, he came a lot later. Just turned up on a garden tour I went on and we clicked. Niall went to one of those expensive Melbourne schools on the bay that smell of boys and rugger but aren’t quite top of the range. I like Niall a lot, by the way. He’s a lot younger than I am, but I like that too. I suspect he was wounded in his youth, well before I met him, but who wasn’t?

Niall appears throughout as a conversational duelling partner, remotely via text or Zoom, to disagree with or poke at Dessaix, to mock or encourage him. His most substantial function is to skewer anything that might be interpreted as a flight of fancy or self-indulgence on Dessaix’s part.

In Rabat for the first time, unable to find the address of Ahmed – the friend he is to meet – Dessaix approaches a man on the street, shows him the address and asks whether he knows it. The man, it turns out, is Ahmed’s uncle. Dessaix experiences this encounter not as an accident but as “a cosmic oneness coming all at once into view”. Niall receives this tale of astonishing serendipity with arched-eyebrow cynicism: “Why would the universe care about you?”

In an interview, Dessaix casually admitted that Niall is fictitious:

He is an aspect of me. He is my bossier aspect, and I have a bossy side to me and sort of finger-wagging side. But he’s made up.

The division of Dessaix’s personae appears, in part, to be a strategy to avoid a pitfall of autobiography: the stable representation of its subject, the neat encapsulation of a soul. In Dessaix’s view, we are far too multifarious for that.

A recurring theme in Chameleon is the trying out of various metaphors and models that resist the notion of the body as a shell for an essential self. Dessaix is a “node in an infinite web”, a performer in a “shadow play”. Perhaps most extravagantly, he writes about the importance of his arrival in Morocco at only 22 years old:

It dawned on me, as I wrote in my diary later, that Morocco stood for ‘my ideal other side – masculine, handsome, exotic, intimate’. Not better or more deeply rooted, but ideal. Skin me and that is what you’ll see: Morocco.

The metaphor of skinning is suggestive in its melodramatic incoherence (there is a sharp dissonance in describing the self under the skin as an “other side”). Despite the effort Dessaix puts into avoiding easy metaphors that rely on a cleanly distinguishable self transcending our physical form, he finds his essence in Morocco.

Irreconcilable images

“How attached we humans are,” Dessaix writes, “to a second, lookalike, spectral self, transcending the brute facts of our bodily existence. How attached I have been to it, against my better judgement, for most of my life.”

These contradictions, these irreconcilable images, these inevitably clumsy commitments to metaphysical structures of surface and depth, permit Dessaix to capture the riotous panoply of existence: “in the details of any human being’s life there are thousands of contradictions, surely”. These contradictions exist not as obstacles to self-understanding, but rather prompts to look “beyond the visible”.

When Dessaix declares that he has “no concept of the sacred at all”, I take him to mean that he does not find it useful to distinguish between the sacred and the secular. Experience and being are best understood, in general, as possessing a “spiritual richness” – if one can only muster the right kind of attention. This kind of attention Dessaix believes to be increasingly rare these days. “Are we left with Gwyneth Paltrow?” he sighs.

The book’s title indicates these struggles with questions of essence and identity. A chameleon’s transformations respond to its environment, but they are surface transformations. Are these creatures’ shifting colours a disguise, concealing the authentic interior, or are they simply evidence of one aspect of the self, soon to make way for one of many other incongruous aspects?

There is no definitive answer, only the conflicts and inconsistencies in which Dessaix invites us to revel.

Chameleon is not a collection of essays, as such, but it is essayistic. The conversations with Niall and Thomas Robert remind me of Michel de Montaigne, the inventor of the modern essay form. Montaigne’s essays are exercises in self-reflection, written in the voice one might use to regale a friend, a voice of lively conversation.

Such writing allows for backtracking, self-flagellation, challenges, paradoxes and grand declarations cheekily inviting riposte. Rather than trying to make sense of a life as a coherent series of events, Chameleon conveys the complex formation of a human voice, a literary voice. As readers, we have the pleasure of engaging with that voice, while learning to consider the nature of our own.

In the interview mentioned earlier, Dessaix revealed that the book’s working title was The Balancing Act. His balancing instrument, as he wobbles across the sea of his many curious selves, is the well-wrought sentence, a sentence that can accommodate all sorts of incongruities if it is only beautiful. Dessaix’s is a life resolved in language.

Dan Dixon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.