MOST Baby Boomers would remember the words to Joni Mitchell's tune, Big Yellow Taxi.

One of its key lyrics goes: 'Don't it always seem to go. That you don't know what you've got, till it's gone . . . They paved paradise and put up a parking lot.'

That's progress for you. For suburban Mayfield (once part of Platt's Estate), some 200 years ago was regarded as a paradise by the Awabakal people. They lived in what was then an Eden of plenty, according to local author Cath Chegwidden, who has turned her attention once more to this fascinating area of Lower Hunter history.

The district's first European settler was John Laurio Platt who acquired his grant in 1821 to build his first home here. His land today is recognised as Mayfield West, modern Warabrook, and the site where the future BHP steel giant opened in 1915.

Lower, near the Hunter River, it was largely swampy. But, slightly higher, it turned into paddocks, small farms, vineyards and, finally, grand Victorian mansions and villas were built by wealthy businessmen.

At first, Mayfield residents thought little of the new BHP plant idea. After all, who would build a major steel mill in a pond, as much ground was under water at high tide? Few then suspected that wetland would be filled in, the nearby harbour channel deepened and Mayfield (at Port Waratah) would become the centre of manufacturing industry. BHP became the region's major employer where more than 10,000 workers at its peak toiled day and night on 300 hectares of heavy industrial land.

Even Newcastle MP Sharon Claydon's father worked at BHP as a rigger and she remembers being mesmerised by the massive worksite, still recalling the gaudy spectacle of BHP's dazzling lights after dark while driving across Kooragang Island, itself also a huge (later) reclamation project.

For 84 years, until September 1999, BHP was the industrial hub of Newcastle and the nation with thousands of employees (and their families) dependent on it. Producing up to two million tons of steel each year, in the 1950s the Mayfield site was the largest integrated iron and steel works in the British Commonwealth.

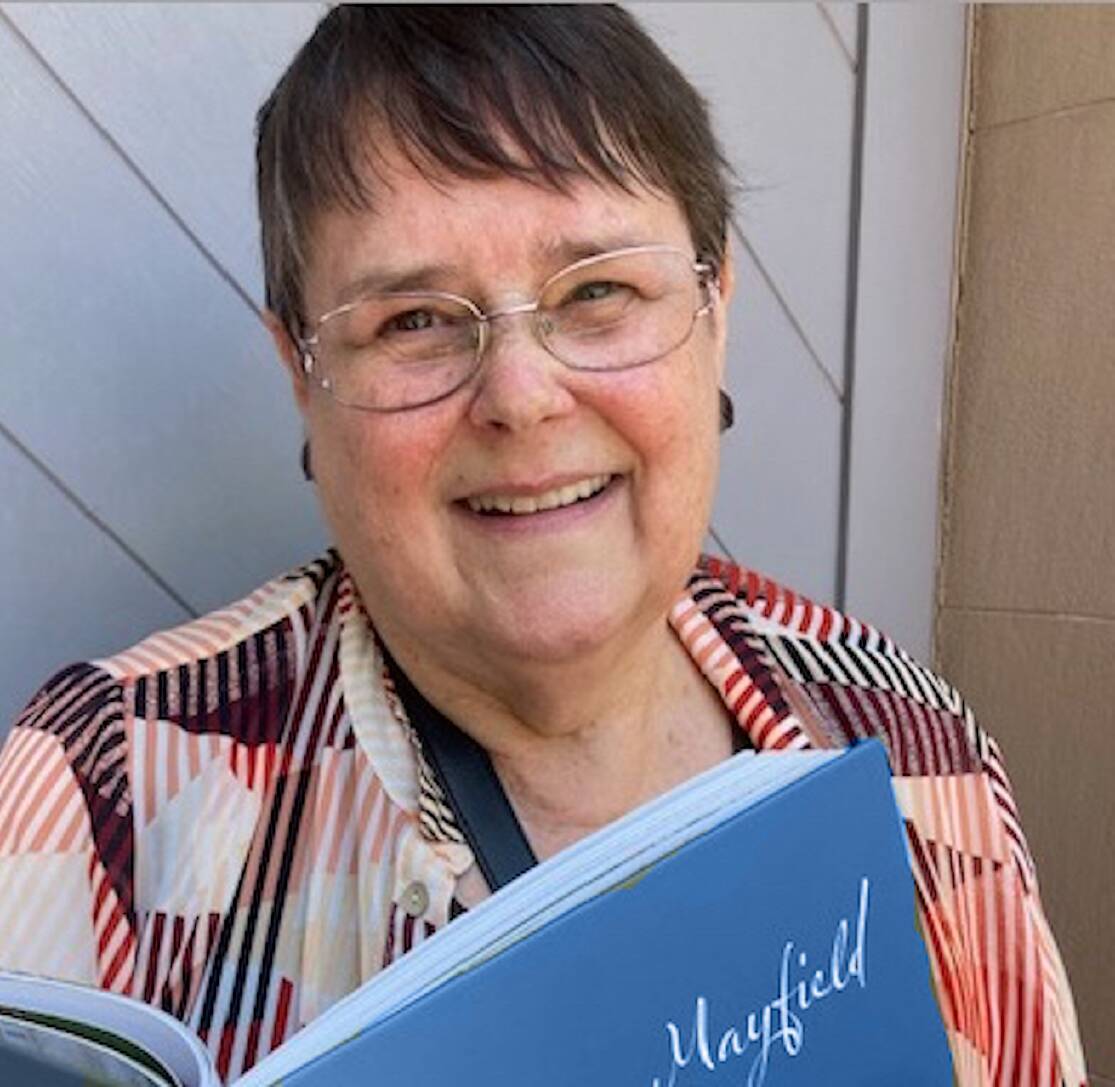

The steel plant vanished almost 24 years ago. Modern city visitors mightn't realise such an employment-generating, but polluting monster ever existed. To revive memories, Cath Chegwidden has just published Mighty Mayfield Then and Now, Book 2: Industry and Change.

Chegwidden's impressive new ode to the suburb is 311 pages and a personal triumph of research. Retailing for $50, the book will probably tell you much more than you ever knew about Mayfield's vibrant past.

But the book's far more than a mere outline of BHP's giant industrial footprint in Newcastle. It covers everything from how migrants shaped the suburb and how new industries were linked to the former BHP, to Great Depression woes, to clubs and sport, including the boxing saga of the 'fighting Sands' brothers to notable personalities, including the beloved district chemist, Colin Glass, and famous aircraft crashes.

I was fascinated initially about the early days before BHP's arrival. 'Pommy Town' resident William Claridge told of how pristine Platt's Channel once was, with plentiful fish and oysters to feast upon.

"Ingall Street ran to the river (at Platt's Channel, now filled in). Sometimes we would catch fish even from the gutters beside the road."

A dairy paddock north of Bull Street was mostly swamp and, when big tides occurred, the mullet ran.

"They would fill the swamp in countless numbers until they were one thrashing mess," Claridge said.

"I've had two books published on Mayfield now," author Chegwidden told Weekender. "I hope it's worth the five years I've put into the project.

"If we don't write the (district) stories down now, who will remember them in 10 to 20 years' time? I was encouraged after the first book came out that people ordered this second one in advance because they wanted to know more about Mayfield.

"I also had to include the story of Mayfield's famous pharmacist Colin Glass (1910-1996). He was without parallel in the community. He worked from 8am to 10pm seven days a week, with almost no holidays.

"But did you know he was a twin? I sometimes wonder if his twin stepped in for him occasionally," she joked.

There is also a remarkable story about the author's late father, Walter Chegwidden, and a little-known naval tragedy in February 1945. It happened onboard the destroyer HMAS Nazim when it was smashed by a rogue wave at night off WA. The ship rolled sharply, tipping the whole of her port side in the ocean. Ten ratings were swept overboard. None of the men's bodies were ever recovered, but one man freakishly survived. That was her father.

"It was our largest loss of life in wartime without being in combat, I believe," she said.

Then there's the extraordinary story of a Sabre jet crashing into a house in Sunnyside Street, Mayfield, on November 12, 1963. It was one of eight Sabre jet fighters on exercise from Williamtown RAAF on a Wednesday afternoon.

By some miracle, no one was killed. The jet slammed into the house as its resident, Edith Tillitzki, 65, was walking out her front door to check for mail. Her house exploded in flames behind her.

Pilot Ron Slater came down near a park with his parachute dangerously tangled in power lines. Two men soon came with a ladder to help him. During research for this new book, Cath Chegwidden was given a tip by a woman in a retirement home that she would never be able to find the names of the electricians who untangled the pilot.

"One was my husband. He didn't like a lot of fuss," the woman told the author.

Three years later, in August 1966, another Sabre jet crashed again in suburbia, this time at The Junction. The pilot did not survive.

After Mayfield's 1963 air crash, the RAAF offered to build Mrs Tillitzki a replacement home in Sunnyside Street. Fearing lightning might strike twice, she declined. She chose a new and safe home at Merewether.

In the 1966 crash, aircraft debris plummeted into a Junction backyard off Kenrick Street, crushing a garage and laundry and burying a car. By a bizarre coincidence, only four doors away from the fatal crash scene, Mrs Tillitzki was living in her new home.

WHAT DO YOU THINK? Join the discussion in the comment section below.

Find out how to register or become a subscriber here.