MLB issued a memo to its clubs Friday outlining a further crackdown on sticky substances, a tacit admission that pitchers began cheating again late last season as they learned workarounds to the routine checks by umpires.

Beginning in spring training games this weekend and throughout the season, umpires will inspect a pitcher’s hand, top and bottom, when conducting random between-innings inspections. Umpires can still examine a pitcher’s hat, belt and glove, as was done last season starting in June.

Eric Hartline/USA TODAY Sports

In the memo to clubs obtained by Sports Illustrated, senior vice president of baseball operations Mike Hill wrote, “If an umpire’s inspection reveals that the pitcher’s hand is unquestionably sticky or shows unmistakable signs of the presence of a foreign substance, the umpire will conclude that the pitcher was applying a foreign substance to the baseball for the purpose of gaining an unfair competitive advantage.” In such a case the pitcher is ejected and suspended automatically.

Hill continued in the memo, “If an umpire observes a pitcher attempt to wipe off his hands prior to an inspection he may be subject to immediate ejection.”

Catchers and position players, who could harbor source material, are subject to the same rules. Starting pitchers “should continue to expect more than one mandatory check per game,” according to the memo. Each relief pitcher will be checked at least once.

MLB is reacting to data that suggests pitchers learned to circumvent the checks. If they did not store a supply of sticky substance on their hat, belt or glove they could avoid detection. The new protocols assume no matter the method, a pitcher who uses a sticky substance eventually will have it on his hand or fingers, thus the additional level of inspection by MLB.

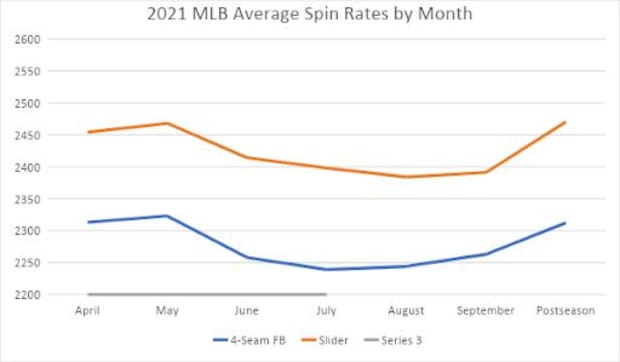

Monthly data on the spin rates of four-seam fastballs and sliders last season show a steep drop in RPMs once the crackdown began in June, but then a climb late in the season:

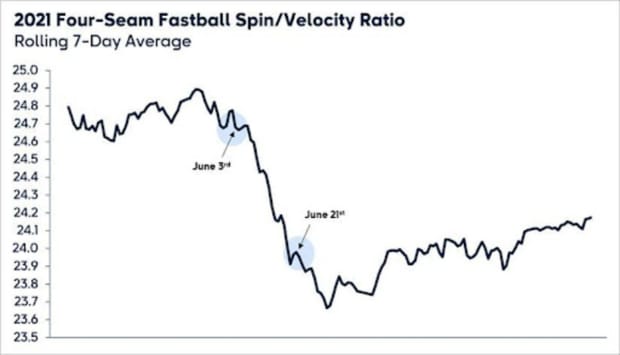

Another way to measure how pitchers worked around the inspections is to examine the ratio between velocity and spin rate. MLB last season began the crackdown with inspections on June 21, but put pitchers on notice of the change on June 3. The fastball spin/velocity ratio dropped immediately, but began creeping up late in the season:

The crackdown began as a response to climbing spin rates and lower batting averages. Pitchers for years had been using substances, such as mixing sunscreen with rosin, to get a better grip on the baseball. New baseballs are rubbed with mud long before the game to remove the sheen, but by game time the mud has dried and can leave a slick residue.

But as devices to measure spin rates and spin axis became commonplace, pitchers turned to much stickier substances not just for grip but as a performance enhancer—specifically to chase better pitch quality metrics than they otherwise were capable of. Among the more popular substances was Spider Tack, which competitors in strongman competitions use to lift Atlas stones that weigh about 100 pounds. As one recently retired pitcher told SI’s Stephanie Apstein and Alex Prewitt for their investigation into sticky stuff from last June, as many as 80% to 90% of pitchers were using some form of illegal substances before the initial crackdown.

From 2017 to the first two months of last season, the average four-seam spin rate increased every year. After the crackdown began, the four-seam spin rate dropped to its lowest level since 2015 (2,252 rpm).

Why do pitchers chase spin? Simple fact: The faster a fastball spins, the harder it is to hit. Every 100 rpms a pitcher adds reduces batting average between four and 18 points:

Batting Average vs. Four-Seam Fastball by Spin Rate, 2021 (RPMs)

* MLB average after crackdown

+ MLB average before crackdown

The effect on offense was immediate once the crackdown began:

Wrote Hill in the memo, “We now have extensive data, including testing by third-party researchers, which shows how the use of foreign substances on baseballs has a material effect on performance. Specifically, foreign substances significantly increase spin rate and movement of the baseball, providing pitchers with an unfair advantage over hitters that our Playing Rules were expressly designed to prohibit.

“We also learned about the dangerous side to foreign substances—that foreign substance use appears to be contributing to an overall decline in control because it enables a style of pitching in which pitchers sacrifice control in favor of spin and velocity.”

The three highest rates of hit by pitches per game since 1901 have occurred in 2019, ’20 and ’21.

Many pitchers had been pitching so long with sticky substances they endured an awkward transition after the crackdown. One of those pitchers, Garrett Richards of the Red Sox, told The Athletic, “It kind of opened my eyes now. Do I feel a little bit like, ‘Damn, we were doing something wrong the whole time?’ Yeah, I do feel that way. But in all fairness, I don’t think we knew we were doing something wrong. So we’re just a product of an era, just like any other era. There was the steroid era. Now we’re the sticky era. So we’re working through it.”

Hitters noticed the difference, especially on elevated, high-spin fastballs. In just the first two months of last season, pitchers threw 1,939 fastballs at least three feet off the ground and that spun at least 2,600 rpms. In the four months after the crackdown, they threw 1,153 such heaters—70% less often. The overall batting average on those super-spin high fastballs was .152.

Outfielder Tommy Pham said to USA Today last year, “It was a joke the way pitchers were cheating. Guys were coming back to the dugout all the time saying, ‘That’s the best slider I’ve ever seen.’ I mean, before crowds came back you could actually hear the Spider Tack [traction] off guys’ fingers. I could tell you who was cheating on every team I faced.

“I don’t think people really understand the benefits of it, but we as baseball players do. If your ball is moving more and it’s sharper, that makes it harder to square up. We were playing Wiffle Ball out there.”