On the morning of December 12, 1910, a young socialite named Dorothy Harriet Camille Arnold left her home in the Upper East Side, New York City, after telling her mother she intended to go shopping by herself for her younger sister’s debutante ball.

However, the 25-year-old had told one of her friends a different version of the story: that she would go shopping with her mother to find a gown for the special occasion.

After Dorothy walked out the door, her family never saw her again.

Almost 115 years later, her disappearance remains the oldest missing person’s case in New York City.

The daughter of Francis Rose Arnold, a perfume importer, Dorothy was born and raised in Manhattan. She attended Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, where she majored in literature and language, and she returned to her family home after graduating in 1905.

New York socialite Dorothy Harriet Camille Arnold vanished over 100 years ago after leaving her home to shop for a dress for her sister’s upcoming debutante ball

Image credits: LOC

Her career aspiration was to become a writer, which amused her friends and family.

When the two short stories she submitted to McClure’s Magazine were rejected, they teased her and tried to dissuade her from pursuing a career in the arts. Still, she remained firm in her decision, using her allowance for a private post office box.

The morning of her disappearance, the heiress walked from her mansion at 108 East 79th Street with $25–30 cash in her possession (the equivalent of almost $1,000 in today’s money).

She stopped at the Park & Tilford store to buy a half-pound box of chocolates and then headed south toward Brentano’s bookstore, where she purchased a book of humorous essays by Emily Calvin Blake titled Engaged Girl Sketches.

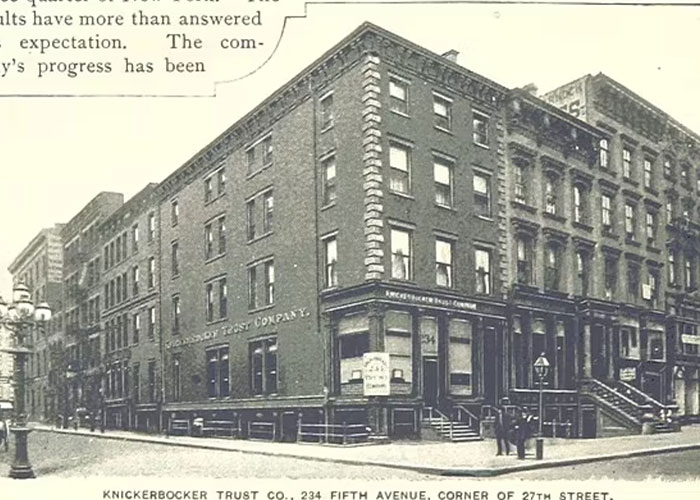

Outside the bookstore, located at the corner of 27th Street and Fifth Avenue, Dorothy bumped into Gladys King, one of her friends. During their conversation—Gladys would later declare that her chum seemed to be in good spirits—Dorothy mentioned she wanted to stroll home through Central Park.

Dorothy’s disappearance remains the oldest missing person’s case in New York City

The Arnolds began suspecting something had happened to Dorothy when she didn’t return home that night. They called some friends to inquire about her whereabouts, but nobody was able to provide an answer.

The following morning, the family decided to hire a team of private investigators.

Calling the police would have meant more resources employed in the search. But it also would have meant leaking the news to the media and potentially staining their social status, which is why Dorothy’s loved ones contacted the Pinkerton Agency.

However, the detectives were unable to locate Dorothy, leading patriarch Francis Rose Arnold to reluctantly contact the New York Police Department for help.

The police held a press conference on January 25, 1911. They reportedly described the missing woman as “5 foot 4, 140 pounds, pretty and stylish in an ankle-length navy dress and velvet hat atop her ‘full pompadour,'” as per National Geographic.

The reward for any information about the case was $1,000 (about $33,000 today).

Her case was closely followed by the media at the time, becoming a source of public speculation

As soon as the news was out, people took great interest in Dorothy’s story and began suggesting different theories about her disappearance.

An article published in the New York Times on January 26, 1911, read, “There is no trace of insanity in the family, and the young woman had never shown signs of a troubled mind, although she was devoted to books and spoke several languages.”

The news also mentioned that the police investigated the theory that Dorothy had run away with a man but discarded it after following up “every man with whom Miss Arnold was known to have been upon friendly terms.

“Neither had she ever had a serious attachment for any man, accounting to members of her family. They all scout the idea of suicide,” the article continued.

While Dorothy was never engaged, she did have clandestine encounters with a 40-year-old unemployed man named George Griscom Jr., whom she had known since her college days in Pennsylvania.

The young heiress left her home with $25–30 cash in her possession (the equivalent of almost $1,000 in today’s money)

Two months before she went missing, the socialite had told her family she would visit a former classmate in Cambridge. Instead, she stayed with George in Boston’s Hotel Essex with the money she obtained by pawning her jewelry.

Friends of the family claimed that the Arnolds were well aware of Dorothy’s relationship with George and strongly disapproved of their union, leading the heiress to see him behind their backs.

It was later revealed that Dorothy’s mother, Mary Martha Parks, and one of her older brothers, John, had traveled to Europe to forcibly interrogate the bachelor in the weeks between Dorothy’s trip to Boston and her disappearance.

While the Arnolds denied all these claims, the father did say during the police press conference that he “would have been glad to see her associate more with young men than she did, especially some young men of brains and position” and that he didn’t “approve of young men who have nothing to do.”

As for George, he stated that he didn’t know where Dorothy was and expressed his intentions to marry her once he saw her again. He also reportedly paid for ads in New York newspapers, signing them “Junior” and asking his forbidden lover to contact him.

Some believe that Dorothy ran away with a man her family disapproved of, while others speculate she died due to a botched abortion procedure

Image credits: New York Tribune

A resurfaced letter that Dorothy had written to George following her frustrating experience with McClure’s Magazine read, “McClure’s has turned me down. Failure stares me in the face. All I see ahead is a long road with no turning. Mother will always think an accident has happened.”

A newspaper article published at the time noted, “To this day, nobody ever has been able to explain what that ominous paragraph meant.”

In 1914, people began speculating that Dorothy had died due to a botched abortion procedure after a Pittsburgh “maternity hospital” known as the “House of Mystery” was raided by police.

Dr. C. C. Meredith, a physician working at the clandestine abortion clinic, alleged that Dorothy had been one of many women who had died on his table from complications during the procedure. He also claimed that the young woman was cremated in the cellar. Dorothy’s father reportedly described this theory as “ridiculous and absolutely untrue.”

Two years later, a convicted felon named Edward Glennoris claimed that he was paid $250 to bury Dorothy’s body in the cellar of a suburban New York residence in December 1910. A man who went by “Doc” allegedly told him that the woman had died at a home in West Point during an operation. Police excavated many homes in the area but didn’t find any human remains.

“A hundred years later, I don’t expect any kind of resolution,” said Jane Vollmer, Dorothy’s great-niece

Over the years, the family received numerous letters from women claiming to be the missing heiress. There have also been supposed “sightings” of Dorothy from all over the country. However, authorities confirmed that both the letters and the sightings were false.

“A hundred years later, I don’t expect any kind of resolution,” Jane Vollmer, Dorothy’s great-niece, told National Geographic.

Jane found out about the young woman’s case after reading about it in the newspaper when she was 30 years old.

“The sensationalism was so hurtful to the family, even today,” said Martha LaFata, another Vollmer sibling. “The best thing I can do for the family is not engage in speculation and respect the fact that these people are gone.”

Jane’s mother, Rebecca, inherited Dorothy’s letters following the death of another relative but chose to destroy them all.

Mark Vollmer, another of Rebecca’s children, said, “If there was a family secret, my mother might have never known. And if she did, it went to the grave with her.”

Missing Heiress Dorothy Arnold – The 115-Year-Old Cold Case That Baffles New York Bored Panda