Joint Chiefs Chair Gen. Mark Milley is handing the reins over to his replacement on Friday. It couldn’t come at a more precarious time, as the West show signs of running out of weapons — and out of patience — with Ukraine.

As the top military adviser to the president, Milley has weighed in on every major decision in the Ukraine conflict, from what weapons to send Kyiv to how to best train its forces. He has a longstanding relationship with Ukrainian Gen. Valerii Zaluzhnyi, commander of the Ukrainian armed forces, as well as other chiefs of defense around the world. He and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, a former four-star general, have led the charge in rallying the West to support Ukraine with modern arms and equipment.

But the war is far from over, and Milley is leaving his successor, Air Force Gen. C.Q. Brown, an array of challenges. As Ukrainian forces push for a breakthrough before winter sets in, there is a growing sense in Washington and Europe that the West may be weary of the fight. On Capitol Hill, hardline Republicans oppose sending additional aid; across the Atlantic, Poland recently said it could not send any more weapons to Ukraine in the short term, and French officials recently hinted the country would soon reach that point as well.

Brown will have to walk the same high-stakes tightrope Milley has over the course of the 19-month conflict, balancing helping Ukraine push back Russian forces without dragging the American military into a full-blown conflict — or starting a nuclear war. At the same time, he will have to continue to weigh Kyiv’s requests for ever more advanced weapons against the Defense Department’s own dwindling arsenal and America’s lumbering industrial base.

The two generals’ personalities couldn’t be more different — Milley a boisterous former hockey player and Brown a quiet tactician — throwing into question exactly how the dynamics of the war effort may shift. What’s not in doubt is the enormity of the task ahead.

The changing of the guard at the Pentagon comes at what could be “a turning point” for the conflict, said Mark Cancian, a senior adviser for the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “If the counteroffensive fails, or if the counteroffensive does not get through the Russian defensive zone in a major way, I think that fears of a forever war will get stronger.”

While Milley and Austin have been criticized for perceived delays in approving weapons, Ukrainian officials are optimistic Brown will advocate for sending more sophisticated equipment. Kyiv has a favorable impression of Brown, according to a Ukrainian government adviser, who like others quoted for this story, was granted anonymity to discuss internal matters. Brown and his second in command in the Air Force, Gen. David Allvin — since nominated to replace Brown as the air’s service’s top officer — were early and consistent advocates for sending Ukraine advanced drones and F-16 fighters, the adviser said.

It’s still an issue. While Biden approved the training of Ukrainian pilots on F-16s in August, Washington has yet to greenlight the donation of long-range Gray Eagle drones, which Kyiv has sought for surveillance and air-to-ground strike.

And as the war enters a new phase, all eyes will be on Brown to see how he handles the road ahead.

“Milley was in the enviable position of having a lot of stuff and a lot of political support so that makes it easy,” Cancian said. “Brown is in the position of having less stuff and less political support.”

Shifting red lines

The job Milley is leaving, and Brown is stepping into, requires balancing the urgent requests from Kyiv with America’s own defense needs at home.

Since Russia’s February 2022 invasion, critics inside and outside the administration say the Pentagon has been too slow to greenlight urgently needed weapons for Ukraine. They say Milley and Austin have a tendency to initially argue that requested weapons are too complex, require too much training, or could provoke Vladimir Putin, only to finally come around to approving them after weeks of unnecessary delay.

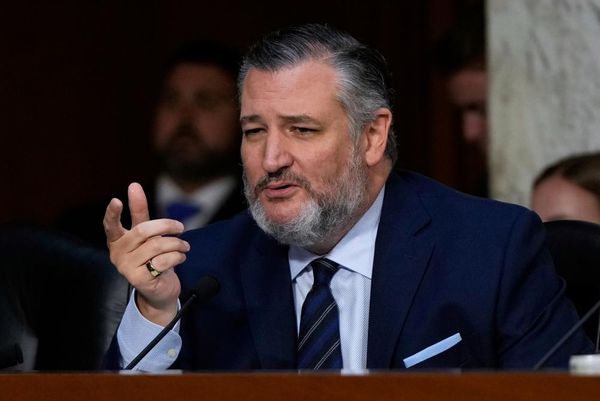

“It’s been frustrating with the administration. We'll talk about a weapons system and weeks or months later, they are delivered,” said Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), noting that at the Pentagon, “Everything was going to be World War III.”

One senior administration official noted how the State Department and the Pentagon are moving at different speeds based on different vantage points.

“State is looking at opportunities, DOD is looking at threats,” the senior administration official said. “Folks at DOD would say they need to think about the pros and cons of each weapons decision, and that responsibility falls on them.”

The long-range Army Tactical Missile System, which President Joe Bidenagreed to send to Ukraine last week after more than a year of debate, is the latest example. The Pentagon initially resisted sending the missiles because they did not have any to spare in America’s own stockpile.

U.S. officials acknowledge that Pentagon leaders take a deliberate, process-driven approach to assessing Ukraine’s battlefield needs against the wider conflict. But Milley and other DOD leaders frequently say their first priority has always been to give Kyiv what it needs for the fight at hand.

“People get wrapped around the axle: ATACMs and jet fighters, and that kind of stuff. And I hear what people say, that it's great,” said Milley in an interview earlier this year. “But this is a real fight in real time, and [we asked], ‘what do you need the most?’”

“That's what they wanted. And that's what we gave them,” Milley said.

Shortly after the invasion, Austin and Milley began convening what became known as the Ukraine Defense Contact Group, a monthly coordination and planning meeting for the defense ministers of the nations supporting Ukraine.

The two generals — one current, one retired — cut an impressive figure at the head of the table, participants say. They are both experienced soldiers, who tend to get deep into the weeds of tactical details in discussions about the war.

Milley and Austin share an easy chemistry and implicit trust that has enabled an effective working relationship, according to those who have worked with the two. There is no perceived power struggle, so the two can disagree and move on, one former DOD official said.

“There’s so much trust there, I think, that there is not any skepticism that there’s some other agenda,” the former official said.

At the Ukraine group’s first meeting, on April 26, 2022, Milley and Austin urged their international counterparts to send all the ammunition and artillery capabilities they could spare, including, for the first time, NATO-standard artillery such as M777 Howitzers.

That discussion became the basis for the Biden administration’s eventual decision to send the U.S. M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, equipped with guided rockets, said Celeste Wallander, assistant secretary of defense for international affairs. But Austin recommended the U.S. send HIMARS only after the Pentagon completed a comprehensive assessment of what role the new weapon would play in the fight, how to train Ukrainians to use it effectively, and whether the U.S. had enough to spare from its own stocks, Wallander said.

At the time, lawmakers and administration officials were frustrated over what they perceived as a lengthy process for the Pentagon to approve sending HIMARS to Ukraine. The timeframe in sending the rocket system, and other weapons initially deemed too escalatory, to the battlefield has made the war “more devastating,” Graham said.

“This idea of not provoking Putin, and letting him bluster his way into indecision on our part, has made the war more costly,” he said.

But DOD officials push back on that, noting that military leaders deliberately chose to give Ukraine incremental capabilities, not only to ensure Kyiv’s forces could use them effectively, but also to avoid the very real prospect of a wider conflict with a nuclear-armed state.

“One thing that was and still is, on my mind every day is escalation management,” Milley said. “The fact of the matter is, Russia is a nuclear-armed state. Period, and they have the capability to destroy humanity. That's nothing to play with.”

Tough road ahead

Sending the HIMARS to Ukraine was the first of many red lines that the Biden administration eventually crossed in the conflict. In each case, U.S. officials have insisted they would not approve the weapon right up until they do so: the Patriot missile defense system in December; M1 Abrams tanks in January; F-16 fighter jets in May; and finally, the ATACMS last week.

Today, U.S. officials are still concerned with escalating the conflict, but they are increasingly focused on ensuring the Pentagon has enough weapons in its own stockpiles to protect against other contingencies.

“If there was a war on the Korean peninsula or great power war between the United States and Russia or the United States and China, the consumption rates would be off the charts,” Milley said in testimony to the House Armed Services Committee this spring. “So I’m concerned... we’ve got a ways to go to make sure our stockpiles are prepared for the real contingencies.”

Brown as chair will have to navigate the same challenges, and he is well-prepared to do so. When Russia invaded Crimea in 2014 and 2015, he oversaw strategic deterrence and nuclear integration for the Air Force at Ramstein Air Base, Germany. As Air Force chief of staff, he supported U.S. commanders in Europe working the conflict, and forged relationships with his counterparts on the continent.

“He was proactively thinking through the areas that they could support us, and that was hugely helpful to me,” said retired Lt. Gen. Jeffrey Harrigian, who commanded U.S. Air Forces in Europe and Africa from May 2020 to June 2022.

Meanwhile, his background as an F-16 pilot will come in handy as the West begins training Ukrainians to operate and maintain the fighter jets this fall, both in the U.S. and in Europe.

But Brown and Austin will still have to navigate Kyiv’s wish list of weapons at a time when political support for the war in both the U.S. and Europe may be waning due to upcoming elections, dwindling stockpiles and domestic politics.

That wish list has in many ways been filled by the U.S. and its allies, and weapons once seen as impossible — F-16s, Patriot air defense, and Leopard and Abrams tanks — have arrived or are on their way. But sending those weapons is only the first step in a more complex dance including building solid, longer-term relationships with both the Ukrainian military and its growing defense industry that Kyiv is eager to get in place.

Brown will have to navigate between the possible and the probable, weighing political realities on both sides of the Atlantic as the war continues to evolve.

“The military challenge that General Brown walks into is … how do you provide training, intelligence and military assistance to try to shift the balance in favor of Ukraine, and is that possible?” said Seth Jones, a senior vice president at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Paul McLeary and Alexander Ward contributed to this report.