Energy secretary Ed Miliband only consulted fossil fuel companies, including oil giants BP, Eni and Equinor, between the general election and the government’s announcement to pump almost £22bn into controversial carbon capture and storage programmes, documents show.

The details of meetings released to The Independent under freedom of information rules show that Mr Miliband only met with broader industry members like academics and clean energy advocates after the 4 October commitment, sparking criticism the policy surrounding the contentious technology was being driven by oil and gas firms.

Green Party co-leader Carla Denyer said that while there was a role for carbon capture in getting to net zero, she warned against it being used “as a fig leaf to continue burning fossil fuels”.

“My concern with the number of these meetings that have been with fossil fuel companies is that the government is listening to lobbyists who are telling them that they should be allowed to continue burning gas with carbon capture and storage attached,” she said.

A government spokesperson said ministers had a duty to meet with a range of stakeholders and have held meetings with representatives from right across the energy industry since July.

“Carbon capture, usage and storage is vital for decarbonisation while boosting our energy independence, and the Climate Change Committee describes it as a necessity not an option for reaching our climate goals,” the spokesperson said.

“The £21.7bn announced last year represents a major success story for British industry and will support thousands of jobs, deliver clean power, and accelerate the UK towards net zero.”

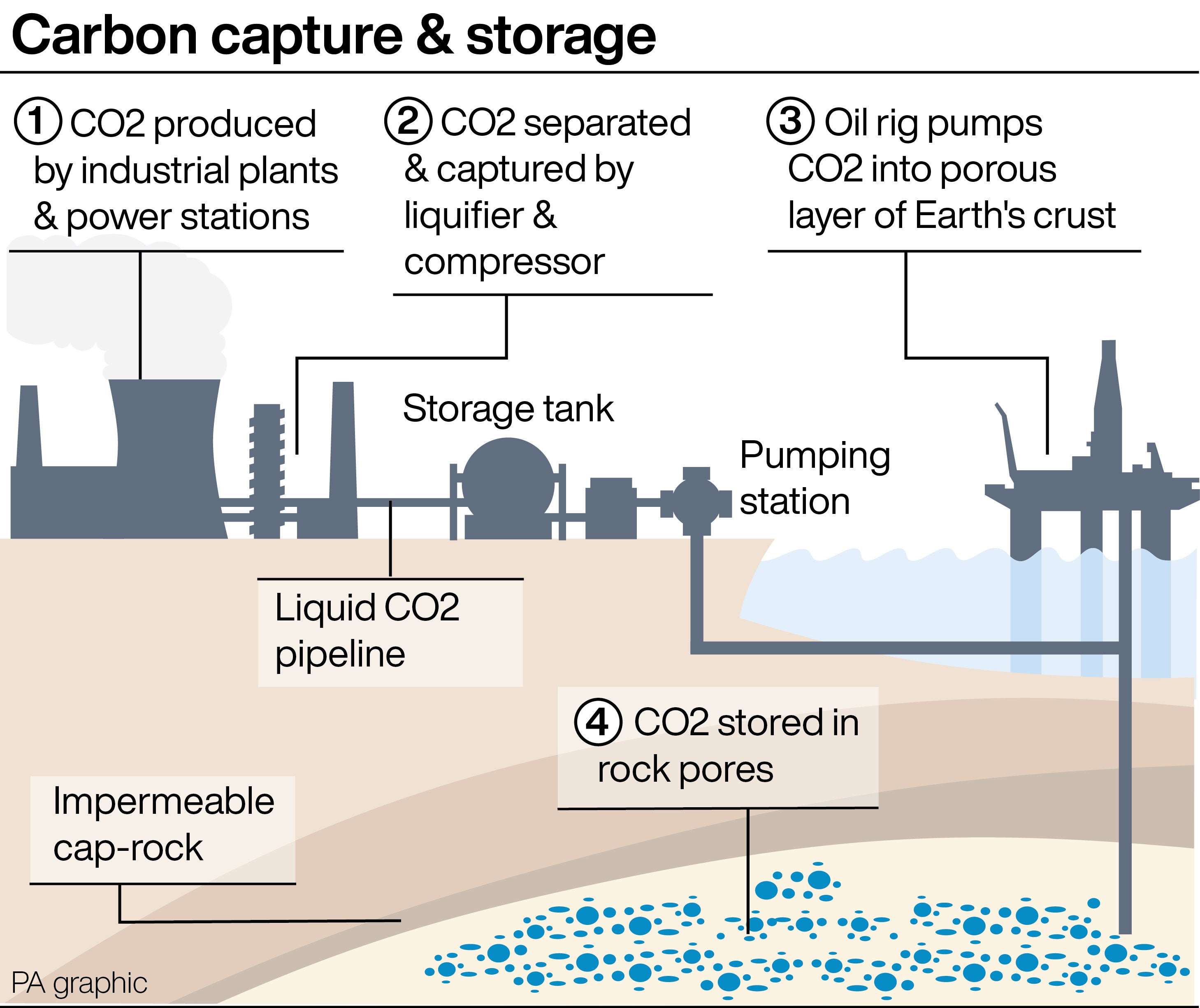

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology aims to take carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas linked to climate change, and pump it below the ground, trapping it and neutralising its effect on the atmosphere. To work, the gas must be trapped there indefinitely. If it leaks, or isn’t captured in the first place, its effect is neutered.

The technology has been used since the 1970s to repressurise old oil wells to get more oil from them. Some scientists now say it can be used to quickly decarbonise industries that would otherwise take years to clean up.

But campaigners say it is being used as a way to prolong the life of the oil and gas industry.

Rachel Kennerley, who campaigns against public investment in CCS through the Center for International Environmental Law, said one of the main problems with CCS was that “it is used to justify the expansion, the production, [and] the use of fossil fuels”.

“The renewables are right there. There are more proven ways to reduce our emissions from energy and electricity than CCS,” she said.

The government wants to focus on four industrial areas in the UK and capture and store 20-30 million tonnes of carbon dioxide a year by 2030. It announced in October it will spend £21.7bn over 25 years on carbon capture, usage and storage (CCUS) and hydrogen projects.

The Independent requested a list of meetings ministers had with companies, organisations and individuals associated with carbon capture since the election.

The meeting records show Mr Miliband had 30-minute phone calls with both the UK’s BP and Norway’s Equinor on 7 July, three days after the general election, with Italy’s Eni on 31 July, and then met Eni in person at Downing Street on 9 September.

On 28 October, he attended a carbon capture, utilisation and storage council meeting, which included representatives from universities and green groups.

In the month after the election, Sarah Jones, minister of state at the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, met with the UK’s Carbon Capture and Storage Association lobby group and attended a CCSA event in parliament in July.

She then visited the HyNet project in Merseyside in July, which aims to make hydrogen, a clean-burning gas, from natural gas by storing the carbon dioxide byproduct. Merseyside and Teeside are named as areas of focus for the funding.

She then met with Harbour Energy on 2 October. Harbour and BP’s joint venture Viking CCS aims to operate a pipeline for CO2 to inject it under the North Sea.

The deal came amid increasing fears from campaigners such as the Center for International Environmental Law that proven technologies which reduce carbon output, such as wind and solar farms, will be squeezed out by unproven attempts to prolong the lives of the oil and gas industries.

Campaigners say this is where the money ought to be spent, on proven technology like windfarms, whereas large-scale carbon capture is some way off.

The Offshore Renewable Catapult, the UK’s research centre for offshore renewable energy, said wind farm capacity costs about £2.5-3m per megawatt of installed capacity. According to analysis by The Independent, it means the government’s plan to spend £21.7bn on carbon capture would buy a wind farm capable of generating up to 8.7 gigawatts of power catering to up to 29 per cent of average UK electricity demand of 30.1 gigawatts.

But Chris Rayner, professor of organic chemistry at the University of Leeds, said the UK Climate Change Committee found carbon capture will be needed for the UK to hit its 2050 carbon targets, and said that the technology should be considered as part of the mix to get carbon output reduced quickly.

He said his company C-Capture designed a chemical process using a solvent to capture carbon dioxide.

“We need them all, and if wind and solar get all the money, then we have a major problem,” he said, adding he was concerned that the technology was being “demonised” unfairly.

“There are a lot of people who are anti-CCS, of course, but it is something we need, and we will need public support for this,” he said.

Benjamin Sovacool, professor of energy policy at the University of Sussex, and an expert on energy policy, said industries such as cement making will be enormously difficult to decarbonise since it wasn’t the energy generation part which emitted the carbon, but the chemical process of making cement itself.

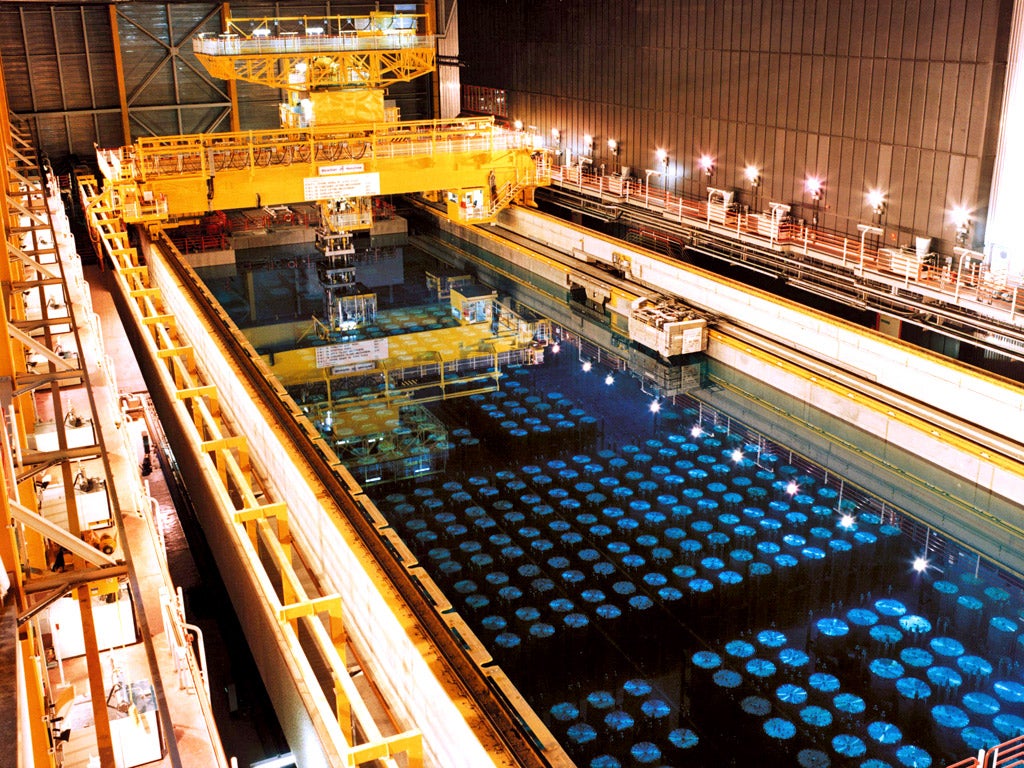

Professor Sovacool said the challenge was making CCS work over the enormous timescales needed to neutralise the danger of the carbon dioxide being released again.

“Once we deploy CCS at even moderate scale, we will need to pursue it in perpetuity, in a similar duration to nuclear waste storage sites. Alvin Weinberg, the physicist, right before he died, wrote a famous article that called CCS the same Faustian bargain that nuclear power was because of the long-lived nature of this infrastructure once you deploy it,” he said.

Even if the public buys into this pact, there can be leaks, he said.

“You can’t ever have a system that’s 100 per cent safe,” Prof Sovacool said. “CCS is one of the backbones of the current government strategy, and it has a lot of risks.”

Ms Kennerley said the big question was then who would pay for these leaks and how would they be solved.

“In 50 years, what happens if there’s a major issue, and all that liability is then on the government to sort out?” she said. “CO2 is a toxic industrial waste product, so the best thing to do with it is not produce any more.”

BP, Equinor, Eni, Harbour Energy and the CCUS Council were approached for comment.