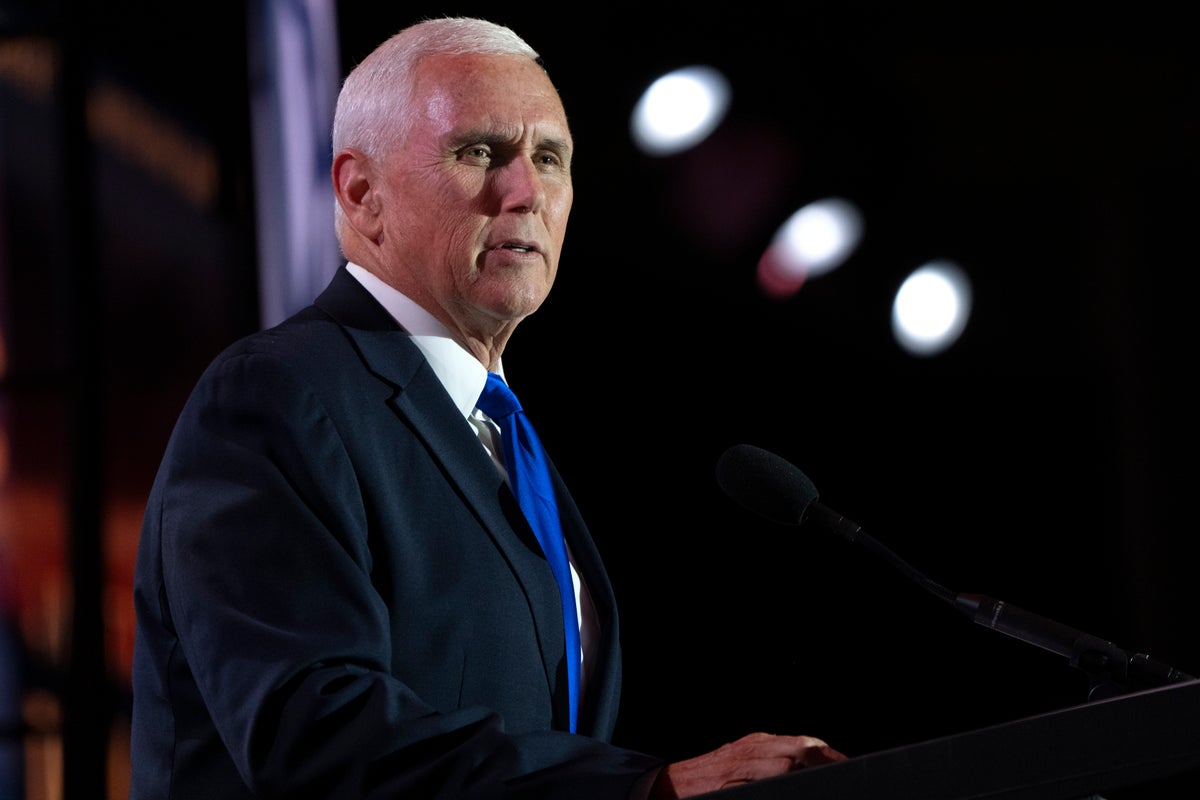

Mike Pence has never been popular, his career marked by a series of uphill battles.

The Indiana Republican lost the first two congressional elections he vied for; then after he was elected into the House of Representatives, he punctured the bubble of GOP support for prominent policies backed by the president.

At the end of his congressional term, he was elected governor of Indiana — by the lowest percentage of votes ever seen in the history of the state’s gubernatorial races.

At the end of his last term as governor, just before he joined the 2016 presidential ticket alongside Donald Trump, his approval rating was the 15th lowest among all governors across the nation.

After his stint in the White House came to an end in 2020, Mr Pence set his sights on another uphill battle: to take the Oval Office. On Saturday (28 October), he acknowledged the terrain was too steep, suspending his campaign with polling at a measly 3.8 per cent.

Mr Pence had built his campaign around conviction — painting himself as the voice of GOP stability in a chaotic primary field led by his former White House boss.

“Will we be the party of conservatism, or will we follow the siren song of populism unmoored to conservative principles?” he asked the crowd at a September speech in New Hampshire. “The future of this movement and this party belongs to one or the other — not both. That is because the fundamental divide between these two factions is unbridgeable.”

Speaking about the 2024 race shortly after that speech, a Pence adviser told The Independent, “This isn’t a new position for Pence to be marching to a different beat than where the party is at.”

Weeks later, Mr Pence has acknowledged that America isn’t keen on his sound this time around. Here, we look back at the road that brought Mr Pence to this moment.

‘Marching to a different beat’

Mike Pence, 64, didn’t begin his political journey as a conservative.

His mother was a Democrat, he explained in his memoir So Help Me God, and he started out his political career as a Youth Coordinator for the Democratic Party in Bartholomew County, Indiana. Mr Pence even admitted he voted for Jimmy Carter in 1980 — not the election that Mr Carter won.

Moved by leaders like President John F Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr, he dreamed of a life of public service, and became interested in public speaking. He was good at it, earning awards throughout his adolescence.

But it wasn’t until college that faith really stuck with him. Much to his Catholic parents’ chagrin, by the end of his freshman year of college, “I was Born Again,” he wrote in his memoir. He grew enchanted with Ronald Reagan and said in his memoir that he couldn’t be “part of the Party of Abortion,” shifting him to conservatism. (His brother, Greg Pence, who is now an Indiana Congressman, is still a practising Catholic; his office did not reply to a request for comment.)

He worked as Hanover College’s admissions officer for two years, before deciding to pursue a career in public service after all; he attended Indiana University School of Law. During his stint in law school, he met Karen Whitaker. He first spotted her — “the beautiful brunette with the guitar” — sitting in the pews of a Catholic church during a Sunday Mass, he recalled in his memoir.

She would later say in a “Pence4Indiana” campaign ad: “When I first met Mike Pence, it was love at first sight.” A year and a half later, in June 1985, the pair were married, Ms Pence reflected. (Nearly 40 years down the line, the couple now have three adult children.)

After earning his law degree in 1986, he started working at a law firm in Indiana, which is now known as Doninger Tuohy & Bailey; name partner Brian Tuohy described Mr Pence as “a very polite, pleasant, nice gentleman.”

In 1987, Mr Pence was approached by a Republican activist to run for a Democrat-held congressional seat in Mr Pence’s hometown of Columbus, Indiana, according to his memoir. He lost, but was undeterred to try again in 1990.

This election in particular was remarkable. Not because Mr Pence lost by a whopping 19 percentage points, but because the output from the Pence campaign was incredibly negative in terms of personal attacks against his Democratic rival, incumbent Phil Sharp.

The press obliterated Mr Pence so profusely that it inspired him to pen an essay: “Confessions of a Negative Campaigner.” In this essay, he apologised for his campaign and vowed to avoid negative ads moving forward—a promise he has largely kept (with notable exceptions, like calling 2016 presidential candidate Hillary Clinton “the most dishonest candidate for President of the United States since Richard Nixon”).

After the 1990 race, the Indiana lawyer took a break from politics, and instead delved into radio talk shows, with his self-described “Irish gift of the gab,” according to his memoir. Others close to him have described him as “quick-witted” and “funnier than you’d expect” — qualities which were in part attributed to his time hosting radio shows.

But by 2000, he had the itch to run again. This time, Mr Pence was elected to Congress, winning by 12 points. And once he had a spot at the table, he was not shy about sharing his views.

The socially conservative congressman

In his memoir, Mr Pence discussed the friendships he made while serving in the House — in part due to the freshly-popped popcorn he put outside of his office, which apparently enticed then-Illinois Democrat Rep Rahm Emanuel to visit.

But he also made alliances with fellow Republicans, describing them in his memoir as a group of “like-minded conservatives” who were committed to “limited government, offering free-market, fiscally responsible alternatives to President Bush’s compassionate conservative” agenda.

He specifically named then Reps John Shadegg, Pat Toomey, Jeff Flake, Jim DeMint, Jeb Hensarling—who Mr Pence called his “closest friend in Congress.” Mr Hensarling, a former Texas congressman, serves as co-chair for Mr Pence’s super PAC: “Committed to America.”

Mr Shaddeg, Mr Toomey, Mr Flake, Mr DeMint and Mr Hensarling did not reply to The Independent’s requests for comment.

He also homed in on his friendship with Jeff Flake, which he said reminded him of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. “Not the actual historical figures,” the Indiana Republican clarified in his memoir, “but Paul Newsman’s and Robert Redford’s interpretations of them in the 1969 film, with me, as I often said, the less physically attractive but more cunning of the two.”

The pair stood out as defiant opponents of George W Bush’s — and many other Republicans’ — policies on domestic issues.

They voted against notable Bush-backed measures, like No Child Left Behind, the expansion of the Medicare prescription drug benefit, and the 2008 Wall Street bailout.

Despite his opposition to many mainstream GOP views at the time, during his tenure, Mr Pence served as chairman of the Republican Study Committee, a conservative House caucus, from 2005 to 2006. Years later, in 2009, he was elected chairman of the House Republican Conference.

The White House summarised Mr Pence’s congressional tenure as “a champion of limited government, fiscal responsibility, economic development, educational opportunity, and the U.S. Constitution.”

However, one notable aspect of his six congressional terms went unmentioned: Mr Pence’s pro-life stance. His anti-abortion position has long been a fixture of his career; so much so that, according to Planned Parenthood Votes spokesperson Shwetika Baijal, Mr Pence “voted for over a dozen” anti-abortion measures throughout his congressional stint.

In 2009, he sponsored the Title X Abortion Provider Prohibition Act which sought to “prohibit the Secretary of Health and Human Service from providing any federal family planning assistance to an entity unless…the entity will not perform, and will not provide any funds to any other entity that performs, an abortion.”

Similarly in 2011, he cosponsored the Protect Life Act which sought to prevent federal funds from being used “to cover any part of the costs of any health plan that includes coverage of abortion services.” The same year, he co-sponsored the Life at Conception Act which attempted to “implement equal protection for the right to life” for every human person “including the moment of fertilization.”

Mr Pence also cosponsored 2012 legislation that aimed to prohibit transporting minors across state lines to get an abortion — a measure that is still trying to be passed today.

In the same vein, it’s nearly impossible to discuss Mike Pence without mentioning Planned Parenthood. Ms Baijal described Mr Pence as “disastrous for sexual and reproductive rights and care,” adding that while in Congress, he was “obsessed with defunding Planned Parenthood.”

He proposed the “Pence amendment” to the 2007 Appropriations Act; he expressed opposition to putting Title X funds toward Planned Parenthood. He said on the House floor, “Millions of pro-life Americans should not be asked to fund the leading abortion provider in the United States.” He added that while Title X funds “may not be used for abortion,” his amendment aimed to prevent “appropriated funds from reaching an organisation that profits from the abortion trade.”

The amendment didn’t pass the House.

On 21 January 2009, as the anniversary of Roe v Wade approached, then-congressman Pence gave a speech on the House floor, saying that using the term “anniversary” made him “bristle” when describing the “the worst Supreme Court decision since Dred Scott.”

His commitment to the cause was so fierce that in 2011, Politico called him a “one-man crusade” against the organisation.

“If Planned Parenthood wants to be involved in providing counselling services and HIV testing, they ought not be in the business of providing abortions,” Mr Pence told Politico at the time. “As long as they aspire to do that, I’ll be after them.” Two days after the outlet’s comment, the Pence amendment finally passed the House.

Mr Pence has also been a vocal opponent of LGBTQ+ rights.

His anti-LGBTQ+ policies throughout his career were so extreme that in 2020, the Human Rights campaign dubbed Mr Pence “the worst vice president for LGBTQ people in modern history.”

Speaking in support of the Marriage Protection Amendment — which sought to “concretely define” marriage as the union of a man and a woman — Mr Pence said in 2006, “in the wake of ominous decisions by activist courts across the land, I come to the well today to defend that institution that forms the backbone of our society: traditional marriage.”

Congressman Pence also voted against the 2007 Employment Non-Discrimination Act — a law that aimed to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation in the workplace — and three years later, in 2010, he voted against the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

According to the New York Times, Mr Pence introduced 90 bills and resolutions during his congressional career — but none ever became a law.

“If the party leaders in DC didn’t always understand my votes and principles, the folks back home did,” Mr Pence reflected in his memoir on his 12 years in Congress. He said by the time he entered his sixth term, “I had a growing sense that my time in Congress was coming to an end, that my work was done.”

Governor Pence

By 2013, the Flake-Pence duo had gone their separate ways: Mr Flake headed for the Senate while Mr Pence headed for Indianapolis, as the newly elected governor. Mr Pence won with 49.6 per cent of the vote, which according to Politico, made him the first Indiana governor to be elected with less than 50 per cent of the vote.

Despite the narrow victory, he had more success passing pro-life measures as governor. Mr Pence reportedly signed every anti-abortion bill that came across his desk while in office.

One measure, Enrolled House Bill 1337, aimed to ban abortions sought due to a foetus having a genetic abnormality. Mr Pence called the act at the time “a comprehensive pro-life measure that affirms the value of all human life, which is why I signed it into law.”

However, its reception was abysmal; the measure was so severe that it even prompted fellow Republicans to blast it.

“The bill does nothing to save innocent lives. There’s no education, there’s no funding. It’s just penalties,” said Indiana state Rep Sharon Negele toldThe Chicago Tribune in 2016.

“Today is a perfect example of a bunch of middle-aged guys sitting in this room making decisions about what we think is best for women,” fellow state Rep Sean Eberhart told the outlet. “We need to quit pretending we know what’s best for women and their health care needs.”

The law made national headlines, and even sparked a lawsuit, which ended in a federal district court in 2022 deciding that the law was unconstitutional. That decision was later affirmed by an appeals court in 2018.

Another headline-making measure that Mr Pence signed into law was the Religious Freedoms Restoration Act. The 2015 law “prohibits a governmental entity from substantially burdening a person’s exercise of religion, even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability.”

Criticism poured in across the board, from Apple CEO Tim Cook to the NCAA to the Disciples of Christ, fearing that the measure would elicit discriminatory practices against those who identify as LGBTQ+. The harsh criticism prompted Mr Pence to approve an amendment to the law.

The then-governor said at the time: “Over the past week this law has become a subject of great misunderstanding and controversy across our state and nation. However we got here, we are where we are, and it is important that our state take action to address the concerns that have been raised and move forward.”

Still, his ratings took a hit. According to contemporaneous polling, Mr Pence’s approval rating plummeted by 15 points from the year prior after the RFRA — and the amendment to lessen the blow — were enacted.

He ended his governorship on a low note, but the plummeting polls didn’t prevent him from being tapped by the presumptive Republican nominee in 2016.

With 2016 came the whirlwind that is Donald Trump. Mr Trump asked the Indiana Governor to be his vice president, just months before the election that would shape the Republican party for years to come.

The misperceived Veep

“I’m a Christian, a conservative and a Republican, in that order,” Mr Pence said when accepting the nomination to be Mr Trump’s running mate.

Although Mr Pence may have made some opponents while in Congress, he likely didn’t expect one of his close friends to turn on him. Mr Pence’s cinematic friendship with Mr Flake famously fizzled following Mr Pence’s decision to join Mr Trump’s ticket.

Mr Flake was a vocal critic of Mr Trump since before he was even elected. Sen Flake, making a statement, refused to attend the Republican National Convention, where his close pal Mr Pence would be formally nominated.

Two years later, in 2018, Mr Flake told Politico about his separation from his old ally: “We’ve taken different paths, but I’m not trying to suggest that mine is a more virtuous path than his. He’s in a position with considerably more power than I have, and there’s something to be said for that.” He added, “If he can influence the president in a positive direction, then maybe that was a wise choice.”

As vice president, Mr Pence was often viewed as Mr Trump’s oh-so-loyal sidekick.

The Pence adviser gave some insight into Mr Pence’s role as vice president. He thought the ex-Indiana governor “had a unique lane as kind of the person who sold the Trump presidency and was intimately involved in it, especially in staffing it.” He had a “reputation for getting a lot of really stalwart pro-life personnel for staff at HHS, State Department, other places,” the adviser said.

Some may have viewed the former vice president as a meek contrast to Trump’s flamboyant persona. He was once described as “cartoonishly loyal as Trump’s vice president” and allegedly once praised Mr Trump every 12 seconds for three minutes straight during a 2017 Cabinet meeting.

Perhaps a contributing factor to this perceived deferential persona is Mr Pence’s reluctance to partake in negative campaigning. This decision comes in sharp contrast to the former president’s seemingly knee-jerk name-calling — and serves as one arena in which Mr Pence unquestionably stands at a distance from Mr Trump in the 2024 race.

This public perception was not without evidence, though.

Mr Pence supported some of Mr Trump’s most controversial moves, like his handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. Also, while he said he could not “defend” or “condone” the former president’s offensive remarks made in the Access Hollywood tape, Mr Pence also didn’t condemn them; instead, he said he would “pray” for Mr Trump.

To many Americans, their first encounter with the fiery side of Mr Pence was on January 6. Mr Pence did not succumb to pressure from his boss to prevent the certification of Joe Biden’s 2020 election victory—in the face of a mob chanting for him to be hanged, no less.

Since January 6, Mr Pence has repeatedly and steadfastly defended his efforts on that turbulent day. He wrote a letter to Congress: “I do not believe that the founders of our country intended to invest the vice president with unilateral authority to decide which electoral votes should be counted during the joint session of Congress, and no vice president in American history has ever asserted such authority.”

In February 2022, he doubled down on his stance, telling the Federalist Society: “I had no right to overturn the election. The presidency belongs to the American people and the American people alone. And frankly, there is no idea more un-American than the notion that any one person could choose the American president.”

He continued to defend his actions on January 6 throughout his 2024 campaign.

Days after the Capitol riot, Mr Flake spoke out about his old friend, telling The New York Times, “There were many points where I wished he would have separated, spoke out, but I’m glad he did it when he did. I wish he would have done it earlier, but I’m sure grateful he did it now. And I knew he would.”

The principled politician

Like Mr Flake, others close to Mr Pence, however, have known long before that turbulent 2021 day that the former vice president could “turn up the heat” when he wanted to.

The Indiana Republican’s record has displayed a fearlessness to voice his opposition to the mainstream — in the form of a vote against a sitting president in his own party or telling his Catholic parents that he had become an evangelical Christian.

His performance on the debate stage in August provided another exhibit of his combative side.

Mike Ricci, communications strategist for Pence’s Committed to America super PAC, told The Independent that he thought debate viewers “were somewhere on the spectrum from surprised or shocked by how aggressive he was” during the event, but, he added, “no one in the field has a longer record of fighting for conservative ideas” than Mr Pence.

“I think people were really surprised to see him be able to be as aggressive as he was on the debate stage,” the adviser to Mr Pence said, adding that people “forget his respectfulness and his gentleness is by choice.” He can be the “bristly porcupine when he needs to be,” he said.

The adviser added, that when he feels the need to “defend his record, or get Vivek [Ramaswamy] clear on what did or did not happen on September 11,” Mr Pence is “more than happy to turn up the heat.”

One word came up a lot when those close to Mr Pence described him: “conviction.”

Mr Pence “is very well grounded on a personal level, in his faith in his core convictions and his marriage and family. He’s an impressive guy,” the Faith and Freedom Coalition founder and chairman Ralph Reed said.

Mr Ricci said, “What has always drawn people to Mike Pence is that he is a conviction politician.” He added, “I’ve always had a great respect for his principled approach, his experience, and that he is always obviously cool under pressure.”

Although coming from a different angle, Ms Baijal said Mr Pence was principled in that he has been “very consistent in his stance on banning abortion.” Mr Pence is the only GOP presidential candidate who supports a federal abortion ban at six weeks — a period before many women know they’re pregnant.

The Pence adviser said that while his stance on abortion may be the biggest “differentiator” from other GOP candidates, that was Mr Pence’s “number one issue.” Instead, the adviser argued, Mr Pence is “in many ways still one of the only more kind of classic conservatives” when it comes to promoting free trade or expressing “concern about overreaching executive power” — à la January 6.

He also possesses the image of a traditional “statesman,” the adviser added.

Pence for president?

Sticking to his principles rather than yielding to popular opinion may be considered noble, and many have long thought that this tendency would not yield him a path back to the White House.

Gunner Ramer, the political director of the anti-Trump Republican Accountability Project, described Mr Pence to The Independent as “a relic of the pre-Donald Trump Republican Party.”

Mr Ramer said the now-dead Pence campaign harkened back to the 2008 or 2012 elections, and “represents a deep misunderstanding of where the base is and what the base wants.” He said that Mr Pence is viewed as “part of the establishment, which is the exact opposite of what Republican primary voters want.”

The former vice president is in a bind, Mr Ramer explained, as he doesn’t fit within the “always Trump” voters, the unwavering supporters of the former president—especially after January 6, which has sparked Mr Trump fans to call Mr Pence a “traitor” —but he also doesn’t really fit with “never Trump” voters, since he was part of the Trump administration.

In his memoir, he reflected positively on his term as vice president: “In four short years, we rebuilt our military, secured our border, revived our economy, unleashed American energy, and, most important of all, gave the American people a new beginning for life.” He then pointed out that three of the five Supreme Court justices who joined the opinion to overturn Roe v. Wade were appointed during the Trump-Pence administration, and in turn, “righted a historic wrong.”

This balance of distancing himself from his former running mate on some issues while promoting the Trump administration’s record in regard to other issues was likely confusing to some voters.

Speaking to The Independent last month, Mr Ricci said the jury was still out on that confusion, asserting that Mr Pence would be able to explain the perceived incongruity.

“I think he’s going to continue to tout that he was a part of and helped drive some of the major successes of the Trump-Pence administration,” he said, Mr Pence would also underscore areas where the two have “diverged.” He gave examples of the former running mates’ differences: January 6 and the war in Ukraine.

In regards to the ongoing war, Mr Pence said at a CNN town hall: “Frankly, when Vladimir Putin rolled into Ukraine, the former President called him a genius. I know the difference between a genius and a war criminal. And I know who needs to win in the war in Ukraine.”

Mr Ricci compared the former vice president to candidates like Mr Trump or Mr Ramaswamy who might generate more headlines due to their more “outrageous” or “bold” comments, while Mr Pence is all about nuance — which is admittedly confusing for some.

Those “nuances get lost,” the adviser said, as most policy questions can’t truly be answered by a raise of hands, like on the debate stage. Mr Pence is an example of a “statesmen-like candidate” who is trying to “give reality its due as far as the things being more complicated than ‘yes/no’” questions, the adviser added.

Mr Pence was “starting in a really difficult spot” because unlike other candidates, who aren’t as well known, his story was already out there, Mr Ramer explained last month. Most people have an opinion of Mr Pence, he said: “his favourables and unfavourables are already built up so much.”

All of this meant “there is a lack of constituency out there for someone like Mike Pence,” Mr Ramer said.

Mr Ricci disagreed, saying there is a “persuadable constituency for Vice President Pence,” especially among longtime, habitual Republican voters.

Although Mr Reed and the Faith and Freedom Coalition are officially neutral in the Republican primary, the founder voiced support for Mr Pence’s record.

He is “really the gold standard for an elected official, representing our values and beliefs. And he was arguably the most pro-life vice president in American history,” Mr Reed added last month. “I think very highly of him. And I think evangelical voters think very highly of him.”

One thing Mr Pence had going for him is his authenticity, allies noted.

Mr Ricci said that at a time when both artificial intelligence and phoney politicians run rampant, “people just want authenticity and that’s who he is.”

Mr Reed called the former vice president a “dear friend.” He recalled a time when they were both at the same speaking event. Somehow, Mr Reed said, Mr Pence had discovered that Mr Reed’s father had passed away recently. Mr Pence came up to him backstage and shared his own experience of losing his father, who had died in 1988. “There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t think of him,” Mr Reed recalled Mr Pence saying. The former vice president also asked Mr Reed a little about who his father was; Mr Reed said he was touched.

To illustrate the Indiana Republican’s character, the adviser to Pence pointed to his unchanging staff. Unlike the Trump campaign, which a Pence adviser described as having “no loyalty” or “sense of respect” with quick turnover, the Pence campaign had “people that have been working for him since the early 2000s, who still want to be around him who could be could be elsewhere but are wanting to work for Pence.”

The Pence adviser added that the reason for that is “he’s a nice guy.” He said that if someone on his staff is in the hospital, he will personally call the staff member and their spouse to check in.

Perhaps one exchange between Mr Pence and his former boss at the end of their term sums up the Indiana Republican best.

“[I’m] never gonna stop praying for you,” Mr Pence told Mr Trump, according to his memoir. The former president replied, “That’s right — don’t ever change.”

If what’s past is prologue, Mike Pence won’t change.

When he suspended his campaign on 28 October at the Republican Jewish Conference, he once again underscored his commitment to his principles: “I’m leaving this campaign but let me promise you: I will never leave the fight for conservative values and I will never stop fighting to elect principled Republican leaders to every office in the land. So help me God.”