Back in May, I took part in a 100km gravel race in Scotland called the Gralloch, finishing 70th in my age group and 361st overall.

I wasn’t particularly proud, but I knew it reflected my level of preparation at the time. I'd spent the prior winter running more than cycling, so I didn't dwell on it too much and instead, I focussed on enjoying the day. How often do you get to ride for four hours off-road traffic-free?

It sparked something in me, and before I'd even got home, I wanted more. So a few days later, I set my sights on the Masters Gravel National Championships.

With a new event on the horizon, I wondered if I could transform myself from an "also-ran" into a contender. The next three months would be a test of not just my physical preparation but my mindset, discipline, and ability to execute a plan.

To plan, I set about 'reverse engineering' my problem. I wanted to understand the demands of the event to prepare myself to meet them.

I then looked to the professional peloton for guidance on optimising equipment and my training. I researched the literature relating to nutrition, undertook a specific strength training program, spent most of my summer training indoors rather than on gravel, introduced heat acclimation training to my plan, and even cut down on my caffeine.

In this article, I’ll walk you through the preparation that turned me from a mid-pack rider into a podium contender. I'll share the methods and the mindset shifts that helped me make this leap. Hopefully, it will inspire you to set your own ambitious goals and provide insights on how to prepare for them.

But before we get into it, there's a lesson that I want to get across right away, and that is that for the first time in my life, the result wasn't important.

I found an intrinsic joy in the process: creating a plan, setting goals and seeing it through. My motivation to ride hasn't been higher in years, and after a few years of dabbling with the odd race here and there, chasing long-lost fitness and praying that the stars will align for long enough that I can magically find the 50 watts I left in 2019, I realise that the missing piece of the puzzle was a big scary goal to get me excited.

There are two key things to take away from this story. The first is that you should put a goal on the horizon that will light a similar fire inside you. The second is that you don't really need to train on gravel to be fast on gravel. This is somewhat course-dependent, but indoor training is extremely efficient, and today's indoor cycling apps are excellent tools to help you achieve your goals.

Gap analysis

The first step to any plan is to understand where you need to be, and where you currently are. Just like planning a route from A to B, if you don't know where you are on a map, you'll be unable to create a plan to get to your destination.

This meant a full analysis of my current situation. I had a bike, I knew how to race, so those weren't going to be my gaps. My main shortcoming would likely come in my fitness. Most of my winter was spent training for a half marathon - running, I know! - so I had some general fitness, but it wasn't very cycling-specific, as my result at the Gralloch had proven.

Most of the cycling I'd done was indoors testing smart trainers for Cyclingnews, so my bike handling skills would probably need a tune-up too.

And at the time of starting this plan, the National Championships were set to be held in Norfolk on a course that I'd never ridden, so I would need to learn the course too.

Creating a training plan

Using the well-trodden acronym of SMART, I needed to create a goal that was Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Timely.

It's all well and good knowing you're not as fit as the competition and that you need to get fitter, but without an understanding of the size of the deficit and how much fitness I'd need to gain, the goal wasn't very specific nor measurable.

So I went to Strava and looked at some of the leading riders at the Gralloch to see how my power output compared to theirs on the day. I then found racers from the 2023 Gravel National Championships to analyse their power profile and understand the power demands of that course.

I looked at my own friends' data, who are better than me but not professionals, as well as data from pros at the front of the elite races.

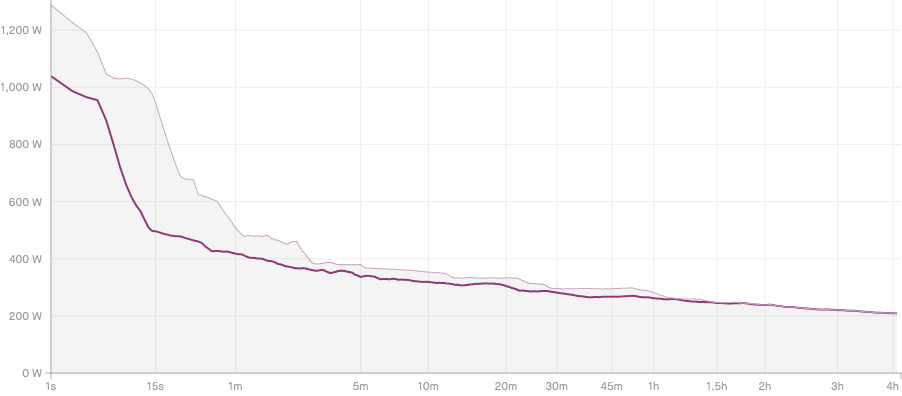

It's a safe assumption that the race demands would be harder than my friends' data, but not quite as tough as the Elite Men's race, and although not everyone uploads their power data and makes it public, enough do that I soon had a feel for how hard the Masters race would be. Comparing that with my own power curve for the year so far, I was a long way off.

It was at this point I created a spreadsheet, a clear sign that things were getting serious.

To begin with, the plan was simply to build my power curve as much as possible. I needed to be more powerful at 1 minute, 5 minutes, 10 minutes, 20 minutes, all the way up to the approximately 3 hours it would take to finish the race.

My deficit was significant, and the 'Achievable' part of the SMART acronym was being stretched – I needed to find around 48 watts over 20 minutes – but I decided to forge ahead regardless. If I could lose 3kg in the process, the target would come down to just 34 watts, and that'd be more achievable given my relatively untrained starting point.

I enlisted the help of the University of Bath's Lead Applied Sport Scientist, Jonathan Robinson, who put me through a skinfold and Vo2 Max test, allowing me to understand my body fat percentage, and at which power output my body starts to switch from its aerobic power supply to its anaerobic system.

I learned that my body fat percentage was around 9%, so while I'm far from overweight, there was a small amount I could lose safely if I wanted. More importantly though, I learned what power output I should be targeting in training in order to drive those all-important aerobic adaptations.

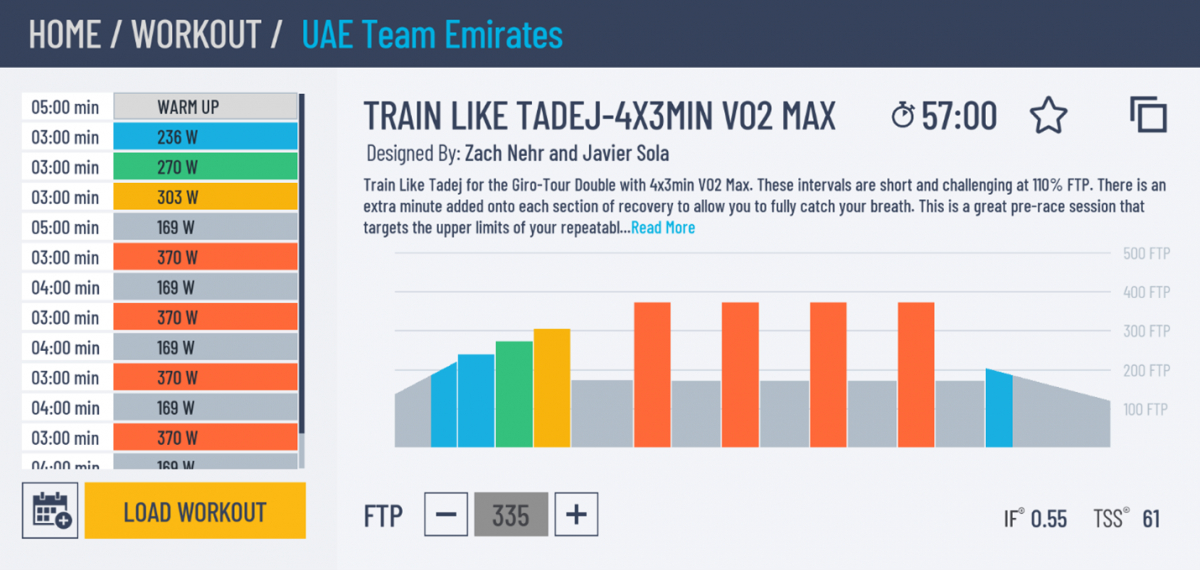

I then turned to indoor cycling apps for my training sessions, including the free app MyWhoosh – the hosting platform of the 2024 UCI eSports World Championships later this year – which enlists the help of WorldTour coaches such as Kevin Poulton and Javier Sola to design its sessions and plans.

Both Poulton and Solar are among the coaching staff at MyWhoosh-sponsored UAE Team Emirates, home of Tadej Pogačar, and Sola is the personal coach to the Slovenian superstar. If their sessions are good enough for the best team in the WorldTour, they're surely good enough for me.

The Tour de France and a venue change

Allow me to jump ahead for a moment. After around five weeks of training, I had a week-long trip to Florence in the diary to cover the Grand Départ of the Tour de France. Sadly this meant no riding, and although I had grand intentions to keep the legs moving with a daily morning run, the long days and busy schedule put paid to this plan. I managed just two 5km runs all week.

While there, I received an email from the organisers to say my race was being moved away from Norfolk, and that it would be held in Gatehouse of Fleet, the home of the Gralloch race which started this whole process. It would also be two weeks earlier than originally planned.

Mixed feelings ensued. It cut my preparation time down by a fortnight, which was concerning given I hadn't ridden a bike in a week at the time. It also meant it would be raced on a significantly hillier course, which doesn't suit my skillset at all.

But it at least meant I had a better idea of the terrain. I had first-hand experience riding it, so I knew that I could disregard bike handling as an issue. I also had a better idea of the ideal tyre choice for the day.

Importantly though, it changed my training plan from being as fit as possible across the entire power curve to a single, highly-specific target.

The course would follow most of the Gralloch's route, which goes straight off the start line, around a corner and up an 18-minute climb, before a 3-minute descent and another 8-minute climb. I am not the most aerobic of riders, I'm definitely more of a sprinter than a time triallist, and at 76kg, not the most adept climber. It was going to be tough, but if I couldn't get over the first climb with the front group, my race would be over, so my new goal was clear.

If I could do that, and then dig deep to get over the second climb, the shorter subsequent climbs later in the day should also be achievable. In a three-hour race, my first finish line would come after just 20 minutes.

I revisited the gap analysis to break down the climb from the Gralloch earlier in the year and worked out that I'd need to hold somewhere between 345 and 360 watts for 18 minutes.

Very quickly, my focus was laserlike and my motivation was high.

However, any professional will read that and tell you that my goal, while highly SMART per the acronym's definition, wasn't actually very smart.

It's what's known as an outcome goal, and it's not entirely in my control. For example, if I got sick prior to the race, I wouldn't be able to hold the power needed. Or if someone turned up on the day and rode at 430 watts for the first climb, no amount of training would get me to that level.

Instead, I needed process goals.

The training

Although I initially planned to seek the help of a coach, I realised I could structure my week appropriately in a spreadsheet and build my workouts in the MyWhoosh app.

My wife and I are great at enabling the other to find time to exercise, and we quickly settled on a routine that would allow me to work this training in without affecting our other commitments.

I planned one long endurance ride a week on Sundays, three hard interval sessions on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, two gym sessions on Monday and Friday, a zone two ride on Wednesday, and as much extra volume as I could squeeze in around, such as commuting to the office or tacking on 20 minutes to the end of hard interval sessions. Adhering to the schedule was my process goal and it was totally in my control.

My hard workouts were selected a day in advance. I find it's better to choose a hard workout when you don't have to do it right away, or I tend to choose a slightly easier one. It also motivates me to eat correctly in advance, knowing how input can affect output. I chose most of the workouts from MyWhoosh's 'Vo2 Max' list, but found myself leaning on the 'Train Like Tadej' workouts too.

The first five weeks of training - prior to my trip to the Tour de France - were spent primarily focussing on building the routine, the volume, and riding in the correct zone to tax my aerobic system. Then upon returning from the Tour, with the new venue, a new end date, a refined plan in place and just eight weeks to go, I ramped up the intensity as much as possible, focussing on Vo2 Max intervals of 350-370 watts (around the upper limit of my target).

I didn't have free rein to repeatedly test my Vo2 Max to measure improvement, so used heart rate and RPE to gauge how difficult each week's training was, then extended the duration per interval, shortened the rest periods between them, or increased the power target after successful sessions.

Nutrition and recovery

Trying to lose weight is a difficult balance to strike when you're also increasing your training volume, intensity, and also trying to recover before each session. So instead, I decided I would allow my body to adapt naturally, rather than actively restrict calories. If the increased training meant I lost a bit of fat, then great, but I wasn't going to chase it.

In fact, knowing I was working much harder, I actually increased the amount of food I ate, but perhaps the most important thing I did was improve the quality of the food going in.

I'm not a performance nutritionist, but I believed I could stack the odds in my favour by focusing on healthy whole foods as much as possible. While being less calorie-dense than junk food, I figured this would also give my body the nutrients to help it recover more quickly and fight off any illnesses that might otherwise come my way.

I also adopted a 'fuel the work' approach, where quite simply, if I had a big training ride coming up in the next 24 hours, I would eat carbohydrate-rich meals, and if I didn't, I would cut back and focus on additional protein to aid recovery.

Recovery became an important factor, and having listened to various podcasts on performance improvement, I realised that consistent sleep and wake time could be another area I could improve. I banned caffeine after 3pm, switching my regular evening cup of tea to decaf, and gave myself a new process goal of going to bed at 10pm.

The optimisations

Here's where things get nerdy, because as a tech journalist for a cycling website, I have a deep interest in the things that help a rider go faster. It's the reason we spend time in wind tunnels testing superbikes.

Around six weeks before race day, I introduced heat training by riding on the indoor trainer with my winter kit on and the fans turned off.

I introduced creatine and beta-alanine to try and eke out a little bit of performance from those hard Vo2 Max sessions, and I added hydration tabs to my bottles following a few weeks of using a Nix Biosensor to work out my sweat rate and sodium loss.

Perhaps most importantly, though, I increased total carbohydrate intake and focussed on building my on-bike fuel intake so that my gut could handle 120g per hour in the race.

On the equipment side, I procured a new aero gravel bike with 34cm wide handlebars, the new SRAM Red AXS XPLR groupset and the accompanying Zipp 303 XPLR wheels with their 32mm internal rim width. I upgraded the bottom bracket to a CeramicSpeed version, and added a pre-treated UFO chain from the same brand.

I wore a time trial skinsuit, complete with number pockets for added aero gains. I paired this with our fastest aero helmet from our wind tunnel helmet test, the S-Works Evade III, and a pair of Spatz aero overshoes on top of my S-Works Recon Lace gravel shoes.

Knowing I'd need more water than I could carry in two bottles, I wore a hydration pack inside my skinsuit to ensure I was as aero as possible.

My tyre choice was the 40mm Schwalbe G-One R - I was unable to get a wider version in time for the race, and would have preferred to go with 45mm, but I had to make do with what was available. I experienced quite regular rim strikes on the 45mm Goodyear Inter tyres at the recommended pressures, and have ridden and raced the G-One R multiple times before with success, so made the decision to switch.

The race

I'm happy to report my training was successful. As expected, the race blew apart on that first climb, with the eventual winner and one other putting in a big effort to string the race out.

I was slightly distanced towards the top of the climb, but as the pace eased over the top, another rider and I were able to bridge back up to the leading duo to form a four-man break. That quickly swelled to five as someone else bridged the gap, but went back to four almost as fast when that same rider punctured.

The four of us rode well together at the front of the race, and I soon realised my first goal had been achieved. I was at the front of the race, rolling turns with the fast boys just three months after my disappointing 70th place. Sure, it wasn't the elite race – maybe that's next year's goal – but in that moment, I felt immensely proud of how far I'd come.

Punctures stopped two of the others, and for a long time, it looked as though I'd secured a 2nd place. Unfortunately, a puncture of my own with just 3km to go put paid to that, and as I stood trailside plugging my tyre, I watched as three others rode past. I eventually finished 5th – 4th in my category (19-34m) – a single spot off the podium.

I came away with a great sense of pride, rather than disappointment at missing the podium.

However, the job isn't done. I have another race next week, and then I'll be setting my sights on 2025. If I can achieve that trajectory in just three months, I wonder how far I can go in a year.