Local politicians don’t always become well known outside of their own circles. But in 2016, Michael Tubbs captured national attention after winning the mayoral race in Stockton, California, about 80 miles east of San Francisco. Despite being known as the most racially diverse city in the United States, Tubbs was Stockton’s first Black mayor, and also its youngest. (He was just 26 when he won the election.)

Even if you’re not from California, it’s still possible you’re familiar with Tubbs’s political legacy. In 2019, he launched the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration, a landmark guaranteed income project. Under Tubbs’s leadership, the program randomly picked 125 people to get $500 a month for two years. The money wasn’t earmarked for any particular purpose. People could use it for whatever they needed, and there were no strings attached.

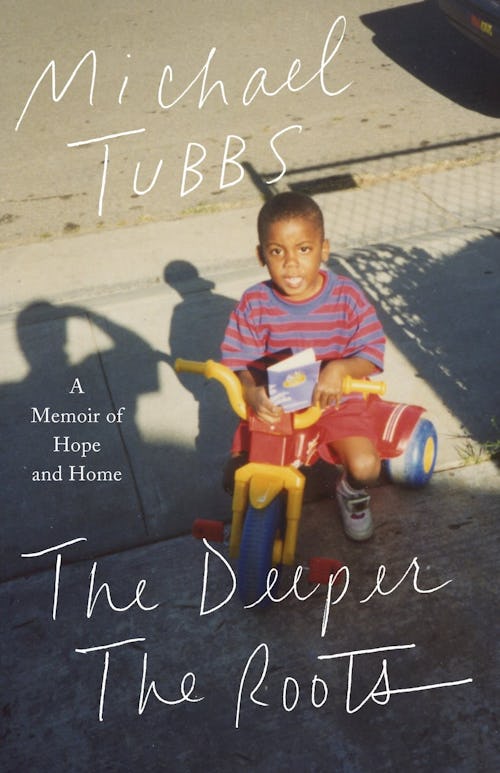

In addition to SEED, Tubbs created Stockton Scholars, a universal scholarship and mentorship program that he raised over $20 million for. Eventually, he began the Mayors for a Guaranteed Income network to advocate for similar programming nationwide. Through his anti-poverty work, Tubbs became a rising Democratic star. But now, a year after losing a re-election bid that many assumed Tubbs would have in the bag, he’s back to share his story in his own words: His new memoir, The Deeper the Roots: A Memoir of Hope and Home, drops Tuesday.

Over the phone, Tubbs tells Mic that his writing journey began in 2017 with a book deal, but it took him three years to actually complete the first draft. “[It] was difficult because it wasn’t researching some other person,” Tubbs says of the writing process. “The idea is kind of researching yourself. Thinking about all the experiences that made you who you are.”

“Luckily,” he quips, “I was only 27 years old when I started. I didn’t have a lot of things. Even still, it’s 200-plus pages.”

Poverty is a recurring theme in Tubbs’s memoir, too. The issue is so important to Tubbs because of how deeply impacted his home state is. While California is often thought of as one of the most progressive states, it still has the highest level of poverty in the U.S., and kids are especially vulnerable. Among kids ages 0 to 5 in the state, about 25% live in poverty, per the Public Policy Institute of California.

In early 2022, Tubbs will continue his anti-poverty work when he launches his new nonprofit, End Poverty in California. He describes EPIC to Mic as “an effort to elevate the issue of poverty in California to one that is politically salient.” In other words, he says, the nonprofit will not only work on public policy but also collaborate with community leaders to disrupt ongoing narratives about who is poor and why.

Throughout the years, Tubbs has been the subject of multiple interviews and documentaries, like the 2020 HBO original Stockton On My Mind. So it’s not too hard to find information about his life and background. But while Tubbs says he appreciates those other projects, his memoir is able to reach areas that they could not.

“[Other projects] were always through somebody else’s gaze, through somebody else’s interpreting. This is really me as the narrator, curator, and producer,” Tubbs says. With that, Tubbs is able to not only reflect more deeply on his childhood, but also on the people by whom he was surrounded and loved.

“I didn’t feel the need to project an image that everything will be fine and we just keep climbing. No, this is hard. This is difficult. This is scary.”

In particular, Tubbs’s memoir is an ode to Black women. “Every chapter is like a new Black woman who’s helping me, nurturing me, and supporting me,” he says. “What often gets missed in translation when people talk about me is I am the product of the love, prayer, support, mentorship, and holding accountable by this amazing chorus of Black women who I’ve been lucky to have in my corner.”

He tells Mic, “This memoir is really about how I feel. That’s what makes it different. I didn’t feel the need to project an image that everything will be fine and we just keep climbing. No, this is hard. This is difficult. This is scary. I think that’s what people will learn from. It’s not in the win — it’s how you feel getting to the win.”

Of course, one topic the memoir must also address is losses, and that includes Tubbs’s 2020 re-election bid. When Tubbs conceded the race to Republican challenger Kevin Lincoln, it came as a surprise. People scrambled to figure out just what went wrong. And while there are certainly multiple factors to consider (like anti-Black racism), most of them were exemplified by a blog called 209 Times, named for a local Stockton area code.

In 2021, it’s hard to imagine a time where people weren’t thinking about the internet and social media’s impact on politics. Tubbs says, “Being so young, you would think I would be the most current on social media. But I started politics in 2012. So, Facebook was never really a key part of my political communication strategy. I had no idea how much people were getting their news, information, and perceptions from Facebook.”

It was on social media platforms like Facebook that campaigns against Tubbs first took hold. Launched by Motecuzoma Patrick Sanchez, who ran against Tubbs in the 2020 primary, 209 Times spent Tubbs’s entire term railing against the mayor. As Politico reported, the blog gained a following of nearly 120,000 people and 100,000 on Facebook, and its posts were widely shared within city circles on both platforms. (The whole city of Stockton has a population just over 300,000.)

Posts included memes that specifically drew on anti-Black tropes. Politico reported that one meme showed Tubbs as a crack addict with the text, “Got any more of that taxpayer money?” Another showed him holding a martini with the words, “When you’re too busy living your best life to notice your city’s on fire.” It also included false accusations that Tubbs stole money from the city.

“It’s so hilarious because I was good at raising money for the city ... and that became a negative. ‘Oh, more money for Tubbs to pocket,’” Tubbs tells Mic. “But if your worldview is that Black people are inherently criminal, particularly Black people in power ... They really prey on people’s biases.”

The disinformation campaign’s success, Tubbs says, was heartbreaking. But he also understood why it worked, pointing to Stockton’s low literacy rates. Plus, as Politico reported, Stockton is basically a “media desert”; the local newspaper, The Record, only listed five reporters on its website in 2020. As former California state Sen. Michael Machado told the outlet, when you don’t have local media, “there’s no fact-check there, and [209 Times] got a big following because they talk red meat.”

Overall, 209 Times captured how white supremacy operates in the country. As Tubbs tells Mic, “For every progress there’s backlash. For every [Barack] Obama, you get Donald Trump. In the history of this country, signs of racial progress [are] oftentimes met with white supremacist backlash.”

“It really taught me the importance of naming racism [and] white supremacy,” Tubbs continues. “My strategy as mayor was that, ‘I’m above this. No one’s going to believe this. If they go low, we go high.”

But by exploiting people’s biases, the disinformation campaign “slow[ed] down progress and undermine[d] my ability to govern,” Tubbs writes in his memoir.

Looking back, Tubbs says, “You don’t have to go low, but you have to go direct. You have to address what’s being said. And be more explicit from the beginning about why this is dangerous, about who is funding this. About why this isn’t news.”

“But,” he notes, “it’s hard to do all that and be mayor.”