Born in 1946 in Harrow, Middlesex, Michael Rosen is one of Britain’s most celebrated poets and the creator of classics such as We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, Little Rabbit Foo Foo and Michael Rosen’s Sad Book. The children’s laureate from 2007 to 2009, he has continued his success in the digital era with his YouTube channel, Kids’ Poems and Stories With Michael Rosen, a collaboration with his son Joe, a film-maker. In March 2020, Rosen spent more than 40 days in intensive care with Covid, and later released Many Different Kinds of Love: A Story of Life, Death and the NHS, about dealing with the illness and his recovery. Rosen’s new book, Goldilocks and the Three Crocodiles, illustrated by David Melling, is published by HarperCollins.

Michael

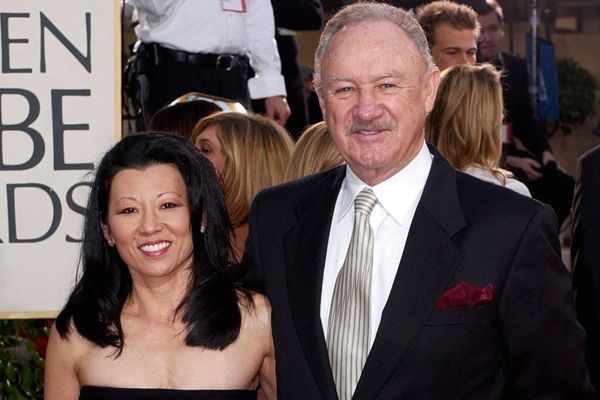

This photograph was taken in 1987 by my friend Chris, who had a boat on the Welsh Harp, a reservoir in London. You can see that I am gooning about, mucking around. I’ve got energy and I’m eating crisps. But this photo is tinged with a tremendous sense of sadness that I’d lost 12 years of my life to my underactive thyroid.

I didn’t know at the time, but when Joe was born, I was deep into a condition called Hashimoto’s disease, where your thyroid is under attack. One of the effects is a kind of indifference to the world and to danger or any extreme emotion. Your feelings are flattened out and you sit there nodding like a wise buddha. But you’re not wise, you just have something wrong with you that renders you slightly idiotic. My mum died in 1976 and it’s a matter of bother to me that I didn’t feel it. The same thing happened with Joe’s birth. I was neutralised to huge life events. By the time he was five, I was taking medicine for my thyroid which revolutionised the way I lived. It was as if I’d just woken up from near death. I became very noisy, and that was disconcerting for everyone around me – I possibly got a bit sparky with Joe as a result.

Even though I’m known for writing poety for children, I wouldn’t say I had any exceptional skill for being around them – I never considered myself any better than any other parent. In fact, when I was younger, I didn’t believe I was the kind of person who would have children. In the mid-1970s, I was walking around in plimsolls and a T-shirt, trying to sell a poem or two, living frugally with no car and no job. I figured that any fatherly feelings I had I would work out with my brother’s kids. That’s no reflection on whoever I was with, it was just what felt responsible. But by the time Joe arrived, I was amazed. He was such a person from the moment he was born. I used to carry him around in a pouch and it was absolutely wonderful.

I never expected Joe to become a poet, and would certainly never stand over him and go: “Write, you little bastard!” My parents were so worried that I would end up in the state of poverty that they had come from that they showed all sorts of anxieties towards me and my brother’s education. If we didn’t do our homework, they would say: “You don’t want to end up like the Mikaelsons.” I’d never even heard of the Mikaelsons! But they came to represent these invisible people from the Jewish East End in the 1930s. I was keen to be less stressed with Joey.

In the end, Joe finished school at 16. When he left I asked him why he didn’t enjoy it and he replied: “It wasn’t funny.” I said: “Well, it’s not meant to be funny, Joey, the teachers are not comedians.” And he said: “The first bit at home with you was funny, you were doing jokes. Then I went to school and it wasn’t funny.” I feel both proud to have made him happy, but sad that school was a disappointment. That I made some of his life good and at the same time a bit sad.

My son Eddie, Joe’s younger brother, died in 1999 [aged 18, of meningitis]. Together, we functioned as a threesome. When we lost him, someone at the heart of the family, everything changed. The dynamic of how we all were shifted. We weren’t three together ever again. Eddie was a loud person who took up a lot of space, physically, emotionally and verbally, and I remember Joe being quite quiet by comparison. Maybe in the many years since I’ve got to know Joe better, in a way.

These days Joe is the boss. It’s been wonderful to work with him on our YouTube channel. Now we’ve between 300m and 400m views, very nearly 700,000 subscribers. A clip from one of the videos has even made me into a meme. I am now world famous for saying the word “nice”. And that’s all thanks to Joe.

Joe

I was definitely happy in this photo as there was a picnic and I got to go in a little dinghy in a reservoir. It was a hot day and we had a lot of fun.

As a child, normality is normality. You don’t have the perspective to compare, so I don’t remember Mick being vacant or ill, even though I now know that he was. In my memories he is very fun, the type of dad who constantly looked for the games in things. Holidays always ended up with a catchphrase, or he’d start it off by saying: “Hey! This week we are reading this!” We’d say: “What book is that?” He’d reply: “Well, I’ve just written it.” It was great.

Mick got incrementally more famous as I got older. When I was very young he was often performing in schools and trying to become a writer in residence. Success has been a journey over time. I really noticed it with Bear Hunt. It was just before I became a cynical teenager and I thought: “Wow, everyone loves it! I wonder if that will stick?” Forty years later and the book is still around.

I always knew Mick did something different from my friends’ parents. When we had “take your kid to work day”, I’d ask: “What are we doing?” And he’d say: “We’re going to a film studio!” One year I ended up with a small part on a television programme called Everybody Here, for Channel 4. I got to have all sorts of fun opportunities, and often I’d be his sidekick on stage. While it didn’t mean I was immediately the coolest person in the playground, I was known as “that guy whose dad came to our school and made us laugh”.

I learned quickly to be self-contained – that if there were 100 people queueing up for an autograph, it probably wasn’t the right time to be discussing what I wanted for dinner.

When Mick was ill in 2020, the days were blazing hot and I’d walk to the park with my little daughter. It was idyllic, but Mick being in the ICU was like a cloud hanging over us. Our mood would be governed by the reports that would come in the evening. How his kidney or heart was doing. We couldn’t see him, which had a surreal nature to it, so I just had to take someone else’s word for it. When I could finally see him, I felt a lot of trepidation: is he going to be all there? He’d just come out of a coma, and couldn’t walk.

Since then, he’s lost some of his sight and hearing, but he’s worked so hard to get back to fitness and is buoyed up by work, as ever.

In fact, I’ve never seen anyone as good as Mick at reading Autocue. Some people stumble, but he does it brilliantly, the first take every time. Even when he was very ill with the thyroid condition, work kept him going, and probably always will.