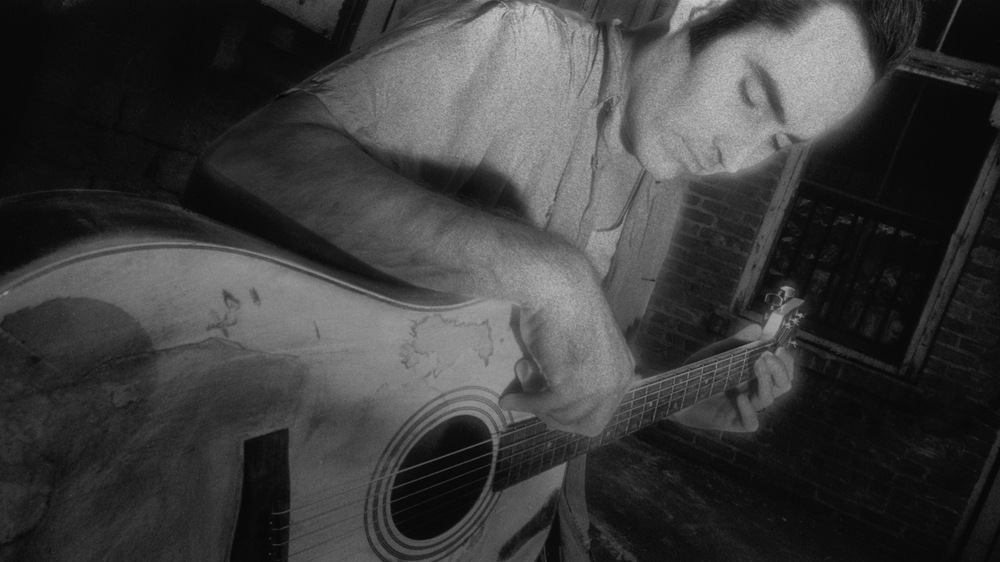

An entire industry wouldn't exist without him, yet few know his name. Michael Knott, a brash and brilliant pioneer of the alternative Christian rock scene who challenged the faithful to examine their faults and hypocrisies, died Tuesday. Knott's cause of death is currently unknown. He was 61.

"To me, Michael Knott was larger than life," wrote Stormie Fraser, his daughter, in a statement. "He was a kind, empathetic father and a creative genius. There is so much more to say about him, so much more to write, but in this time of shock and profound grief, I cannot list all that he did and all that he meant to us. I can only say I love him so much that it hurts. It is difficult to accept that someone with so much of my heart has left this earth."

Born Dec. 22, 1962, Knott came out of Southern California's Christian punk scene of the early 1980s, at first joining the ministry-oriented band The Lifesavors before essentially taking over and renaming the project by the decade's end. Like much of the music coming out of Los Angeles and its surrounding beach towns, his L.S. Underground wrote groove-heavy, funk-tinged, flange-ful alternative rock — think Jane's Addiction and Red Hot Chili Peppers — with a gothic flair and a charismatic frontman who fancied himself a punk Elvis.

The band's 1987 album, Shaded Pain, was a haunting and often hopeless meditation on mortality, abusive church leaders and sins of the flesh. "Our time has come / Let's kiss the cleaver," Knott threatens on "Our Time Is Come," calling out false idols: "Your god is dead / Our God will never leave us." Christian bookstores — then one of few places where Christian records could be bought — banned Shaded Pain. Churches, too, banned Knott from performing following the album's release, foreshadowing many such clashes to come.

Still, those setbacks didn't deter Knott from bum-rushing Christian Contemporary Music once again. CCM is a catch-all term for faith-based music in popular formats beyond gospel and hymns; back then, anything fringe — like punk and electronic music — was still new ground for this traditionalist industry. Knott founded his own label, Blonde Vinyl, and in 1991 made a wild gambit, releasing 10 albums at once with the aim of purposely oversaturating the market. "The only requirement for a band to get signed to Blonde Vinyl is that they had to be musically off the grid," Knott shared in the liner notes for a recent reissue of L.S. Underground's The Grape Prophet. "Breakfast With Amy has go-go dancers at their live shows? Perfect! I'll sign those guys! If there was a band out there — I didn't care if it was techno, I didn't care if it was punk — and they were musically off the grid, I was interested."

His gamble worked. Christian teens and 20-somethings suddenly had a trusted source for music that was cool, weird and heavy ... and that their parents would approve. Through Blonde Vinyl, Knott gave himself and others permission to be real about faith and art, confronting both while entangled in the messy business of mixing them with commerce. The label went bust just a few years later when its distributor went bankrupt. Still, if not for Blonde Vinyl, there would be no Tooth & Nail Records, the game-changing label that was originally conceived as a joint venture between Knott and the company's leader to this day, Brandon Ebel. Tooth & Nail altered the course of the Christian rock industry by launching and legitimizing the careers of MxPx, The O.C. Supertones and Underoath. Ultimately, Knott bowed out of the collaboration, but he did release one album of his own on Tooth & Nail, 1995's Strip Cycle, a surrealist acoustic punk album indebted to the Violent Femmes.

Knott had his brushes with the mainstream. He signed to Elektra Records with his band Aunt Bettys, and much later, auditioned to front the band that would become The Velvet Revolver, a 2000s supergroup spun off from Guns N' Roses. But from the '90s on, he mostly released albums under his own name — recordings that confronted his demons with both bombast and a quietly fervent spirit. He was known to be confrontational, burning bridges with labels faster than his prolific songwriting could keep up with. He publicly struggled with alcoholism, unflinchingly documented on "Double."

"A man after God's own heart is not welcome in the Christian industry," he said, laughing, in a 1998 interview. "I think that the fault belongs to American Christianity — it is cultural. Everyone runs away from drinking and smoking, experiencing and living life, and they end up being extremely disturbed and they lose all their faith and have no hope in the end."

On 2001's Life of David, Knott took on a well-known Bible character. In the Old Testament psalmist, Knott found a tortured and tangled portrait of grace ... and perhaps saw himself. On that album's devastating "Chameleon," he sings:

I am the adulteress

And the penitent man

I'm the cunning culprit

And the little lamb

And I love all God's children

All but one

This chameleon

In the eyes of those who loved his work, Michael Knott understood better than most that grace isn't for the beloved, but the broken.