The New York Times has just run an online series by war artist Michael Fay that is exceptionally moving and thought-provoking. Over the past decade, Fay has seen action as a war artist with US troops in both Iraq and Afghanistan, but his latest journey was to a military veterans' hospital in Richmond, Virginia. In the resulting New York Times blogs, he relays his meetings with three young men severely wounded in Afghanistan. His account of their injuries and rehabilitation is gripping, but what really deepens the reporting are his drawings, reproduced alongside the articles.

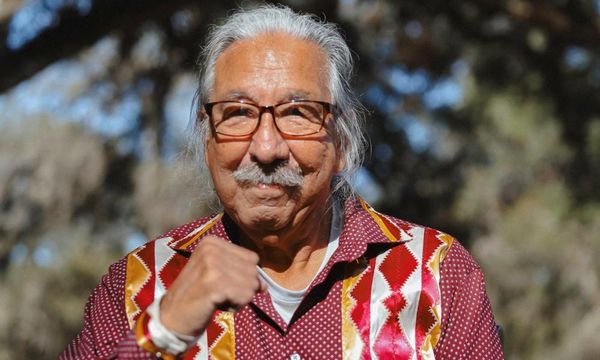

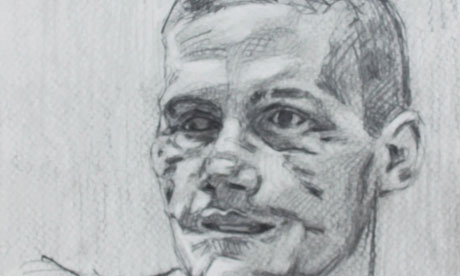

Fay is clearly sympathetic with soldiers and his affinity with them is reflected in the very style of these drawings. "Strong and sensitive" would be the simplest way to characterise his on-the-spot observations. A bold, manly line delineates damaged faces and bodies, but with a softening edge of affection. There is real feeling in the sketches, as well as a painstaking accuracy that vindicates the idea of sending artists to war. Fay's drawings have a disarming humanity that it is hard to imagine being captured by a TV camera. You feel - you hope - these drawings were therapeutic for the men themselves.

All three subjects of the drawings suffered terrible and permanent wounds in Afghanistan. The piece that caught my eye was the second in the series, Scars, in which Fay meets and sketches Lance Corporal William "Kyle" Carpenter, who took the force of a grenade explosion in his face. Carpenter underwent surgery 30 times in nine weeks and allowed - in fact, invited - the artist to portray his rebuilt face.

Text and image come together especially well in this piece, as Fay describes the touching relationship between Lance Corporal Carpenter and his girlfriend, Jordan Gleaton, who is living with him in the hospital. There is a lovely sketch of them together, as well as two superb portraits of the soldier's healing face. Black scars made by ingrained explosive, a ruined eye, a face that in one drawing looks positively noble and in another dreadfully unmade: these are compelling studies.

War is almost too easy a subject for the artist. Grisly violence is spectacular. Wounds are shocking and grotesque. Photography is the medium through which we most commonly see war and it is superb, almost too superb, at showing the colour of blood and the tragedy of injured flesh. As the cultural critic Susan Sontag argued in her book Regarding the Pain of Others, our photographic culture tends to make suffering into a horribly compelling spectacle, remote and lurid. Newspapers have become aware of this, and often end up publishing only the mildest images of war. This is not because photographers are scared to confront horrors, but because the camera is brutal. It can show a burned corpse but not the emotion the photographer felt seeing it. This is why so many news images seem to be of smoke, flame and a desert sky – that way, there is more scope for imagination. With war photography, it is either beauty or terror.

Drawing is different. A good artist who draws a damaged body records not just the scarred flesh but the emotions inherent in the act of drawing itself, and the human encounter between artist and portrait subject. Michael Fay's hospital drawings live up to this potential to be more humane, more nuanced than a mechanical or electronic eye ever can. Drawing does have its uses, and here is one of the best.