The gallery is dark as a church at dusk. The sepulchral gloom is lifted only by a series of small windows pierced into the walls, behind each of which hangs a spotlit painting. At a distance, these look like tiny icons, or medieval panels, and sure enough the figures depicted might be monks or penitents in their black robes and hoods. But come closer and you get a shock.

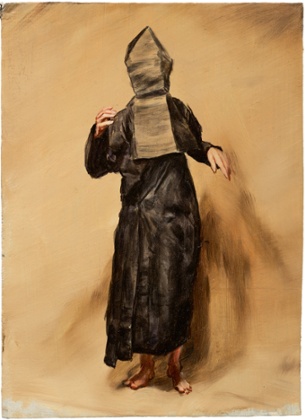

The first figure stands like an adolescent waiting to be photographed by some embarrassing parent, arms dangling self-consciously, the heel of one bare foot half-raised as if eager to be off and out of this weird costume. The second holds the garment to him (or her: each face is entirely concealed) like a patient trying to keep his hospital gown from falling open. The third is apparently dancing, quite possibly to a 2-Tone track from the Specials, given the moves. I have no idea why the fourth has turned his back on us, but the stance appears both sinister and extremely deliberate.

These are only belated impressions. The first feeling – as always with this fascinating artist – is of absolute mystery. The paintings are exquisitely made, consciously crafted in the old master tradition, all their lights and shades perfectly rendered, and the anatomy of each figure studiously considered beneath the monastic black robes. Yet these are scarcely religious paintings.

Borremans was born in Ghent in 1963 and is, as a consequence, routinely described as a Belgian surrealist. But that doesn’t come close to his obsession with illusions and his creation of a parallel painted world. Anyone who saw his last show here in 2005, and it is not easily forgotten, will remember its strange cast of figures engaged in inscrutable actions – the woman raising her hands as if to type on some non-existent machine, the two men in utility wear taking a scalpel to something offstage, the girls in wartime kerchiefs apparently emerging out of the very pigment itself.

The solemn absorption of each figure in whatever they were doing set off conflicting moods – sometimes droll, sometimes disturbing – which remained enticingly on edge. And so it is with these latest works.

The hoods look simply old-world to begin with, so there is the immediate dissonance of the ancient monk striking a modern pose. Some of these figures are even standing against a studio backdrop such as a white sheet or an expanse of unprimed canvas. Perhaps the hood is more like a mitre, a hat or a prop; perhaps the robes are worn more like a dressing gown or theatrical costume.

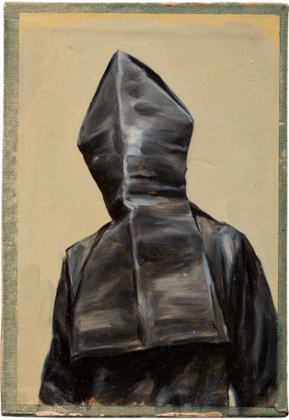

As the series continues, there are overtones of Goya, Philip Guston, Abu Ghraib and the Klan. Borremans keeps all kinds of social and visual cues in play, the figures appearing by turns abject and humiliated, then violent and wild. They ought to be blind, and sometimes are, groping in the sepia light of the painting; but then they will turn upon us as if (in both respects) sighted.

Borremans’s narrative is planted with double-takes. A hood appears in dramatic close-up, as if sitting for his portrait. Another appears with a child-sized hood, as if the image were breeding. Still another raises his hands to his head in derangement, perhaps desperate to escape the painting. The anticipation builds to a climax – and then you climb to the gallery upstairs.

Here the works are much larger and more mysterious. A whole lot of hoods are dwarfed by a vast canvas that they touch in awe, as if it were sacred, but before which they also perform lewd bacchanalian acts. The canvas within the canvas appears to show a massive fiery apocalypse, but the picture is innocently called The Leafs. It is an alarming work, and yet it is also a send-up.

Is Borremans mocking his own eerie creations, or fingering at some deep anxiety about the worship of contemporary art through the parable of false idols? (His own work is in museums all over the world.) In the past, he has tended to a curious period look – puffed sleeves, razor crops, men in duster coats and a certain low-watt 1930s lighting. He generally prefers a mute palette – shifting shadows, pearly reflections, the tawny browns of Manet and Velázquez.

But now there is something quite unexpectedly up-to-date about his scenes, even though some could be set in medieval Spain. The source of this look is frequently inexplicable. So you are immediately drawn into a closer examination of what makes a painting look as it does, and that is – at the very least – what Borremans is about.

Downstairs the hoods seemed almost human; upstairs they have become a race of monsters, miniaturised as if to emphasise the artificiality of the illusion. And then black comedy sets in – those beautifully painted feet start to burn, flames break out of one hood and the painting itself appears to be issuing (or even made of) smoke.

Borremans is a charismatic and prolifically inventive painter. I’ve no idea why his work is not represented in British museums, but perhaps this show will change that. It has at its core the idea of mutinous subjects, resistant to the artist as to the viewer, who in some cases appear to sense our presence, and even to overhear us – the figments of a highly original mind.