More than 100 secret MI5 files have been declassified for the first time, shedding light on the lives of five of Britain’s most infamous KGB spies. New information is revealed about the confessions of Kim Philby and Anthony Blunt, two British MI5 agents who spied for the Soviet Union.

Along with Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean and John Cairncross, the group came to be known as the “Cambridge Five”, with all of them being former Cambridge University students who passed information to the KGB from the 1930s until at least the 1950s.

The documents from MI5 have been made public by the National Archives. They detail the investigations into the group that plagued Britain’s secret service for decades. Their story has shocked and inspired people in the UK and beyond for years – and now more of the secrets are laid bare.

Dramatic confessions, daring near-getaways and never-before-seen suspects are all part of the bundle, which dates back to MI5’s early years before the First World War.

Here are the five biggest takeaways from the MI5 files:

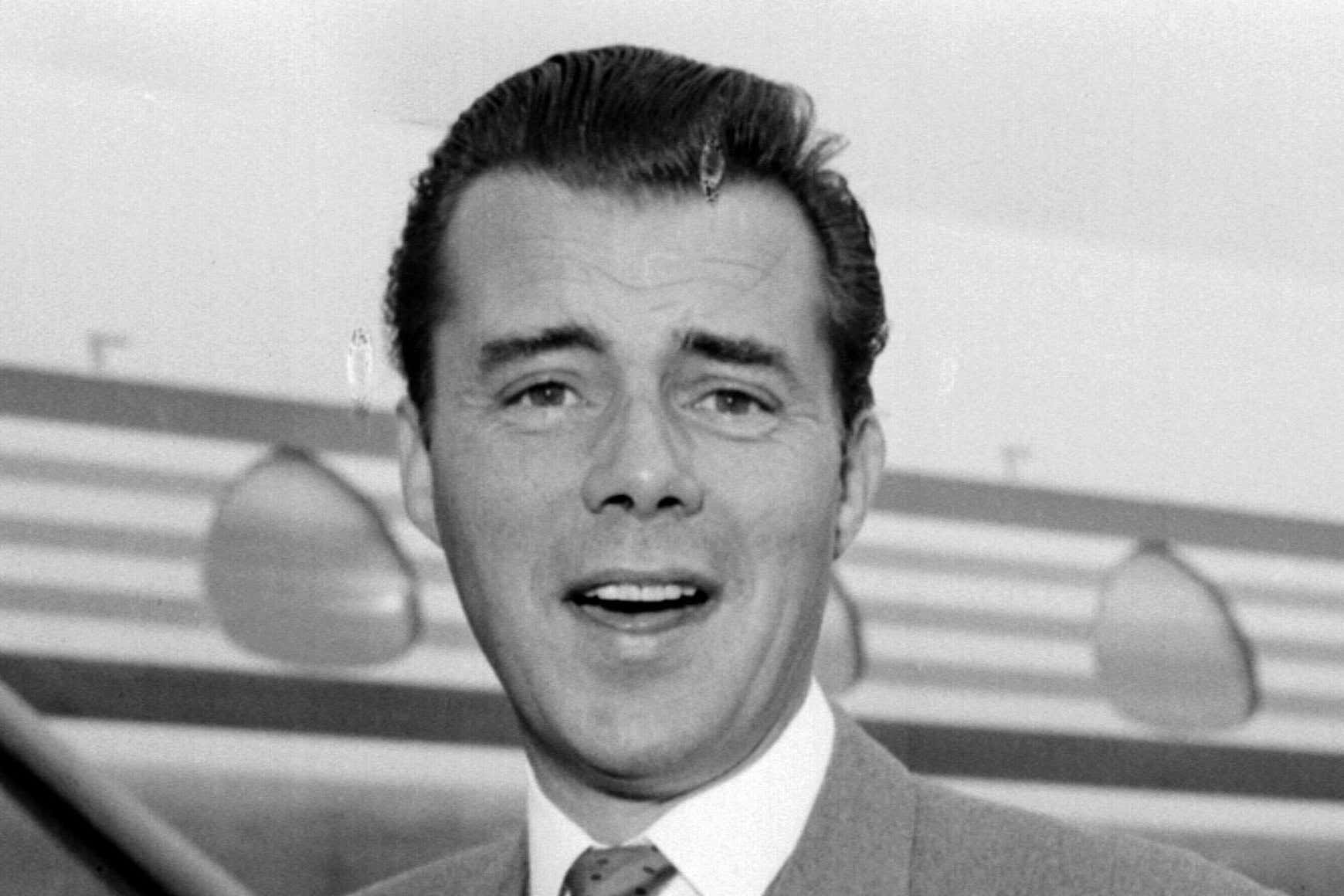

Agents feared film star Dirk Bogarde was a KGB target

Bogarde was warned by MI5 that he could be the target of an “entrapment” attempt by the KGB over rumours about his sexuality.

The documents show that the actor was “clearly disturbed” after learning that his name was on a list of “six practising British homosexuals” which was passed to the Russians.

Bogarde, who died in 1999, never came out publicly as gay, although he maintained a long-term relationship with his manager, Anthony Forwood.

Having made his name in the popular Doctor series of comedies in the 1950s, he subsequently appeared in a number of pioneering films with gay themes, most notably Death in Venice.

After he was interviewed in the south of France, MI5 concluded that he was a “retiring, serious” man who was unlikely to fall victim to any kind of KGB sting operation.

Queen Elizabeth was kept in the dark over Palace spy

Queen Elizabeth remained unaware of the full scale of the extent of spying undertaken by one of her senior courtiers, the papers reveal.

In 1964, Anthony Blunt, the surveyor of the Queen’s pictures and distinguished art historian, finally confessed he had been a Soviet agent since the 1930s, having been recruited when he was a young don at Cambridge.

As a senior MI5 officer during the Second World War, Blunt had passed vast quantities of secret intelligence to his KGB handlers. However, he was allowed to maintain his position at the heart of the British establishment amid fears of a major scandal if he was sacked and the truth became public.

When the Queen was finally told the full story in the 1970s, she was reportedly unflappable – taking it “all very calmly and without surprise” – according to the declassified files.

The decision to ensure she was properly informed came amid growing concern in Whitehall that the truth would inevitably come out when Blunt – who had been seriously ill with cancer – died. Journalists had been looking into the story, and would no longer be constrained by concerns over libel upon his death.

Blunt was finally unmasked by prime minister Margaret Thatcher in a Commons statement in 1979. He died in 1983 aged 75 having been stripped of his knighthood.

Palace spy feared violence from his KGB controller

Blunt also feared that his KGB handler would turn violent when he refused to join his fellow spies Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean and flee to Russia, according to the files.

Amid fears of arrest and that their spy ring was about to be broken up, Blunt’s handler told him to pack his bags and leave the next morning for Paris and from there make his way to Moscow.

However Blunt, a wartime MI5 officer who had become a surveyor of the King’s pictures, regarded the plan as “absolutely insane” and refused to obey.

After his confession, he would recall his interaction with his KGB controller in London, Yuri Modin, who was codenamed ‘Peter’.

“I remember being faintly surprised at his not being more violent,” Blunt said. “I mean, he couldn’t obviously force me to go, but I was rather surprised at his not being more violent.”

‘Enigma’ Kim Philby baffled MI5 agents

Soviet spy Kim Philby was an ‘enigma’ to a top MI5 interrogator, who admitted he could not determine whether the double agent was telling the truth or not.

Jim Skardon, a former Metropolitan Police Special Branch detective, was renowned within MI5 after obtaining a confession from Klaus Fuchs, who betrayed the secret of the US-British Manhattan Project to build the world’s first atomic bomb to the Russians.

However, the newly released files show that Skardon was less sure when coming against Philby, who would later be exposed as a spy. At the conclusion of their interviews he admitted he found Philby to be “more of an enigma than ever”.

“For all practical purposes, his reactions to the things that I thought would worry him most… did not have anything like the effect I anticipated,” said Skardon.

“He really does maintain calm in the most extraordinary way, and possibly this is due to complete innocence.”

The interrogator concluded that a conclusion on the case would likely have to “await the discovery of new evidence.”

Philby said he would do it all again after confession

When he did finally confess, Philby expressed no regret over his years spent as a Russian agent.

The new files capture the dramatic moment in January 1963 when he owned up to his treachery after being confronted by his oldest friend and fellow MI6 officer Nicholas Elliott.

“I have had this particular moment in mind for 28 years almost, that conclusive proof would come out,” Philby said. “The choice actually is between suicide and prosecution. This is not in any sense blackmail, but a statement of the alternatives before me.”

But while Philby admitted that he had been working for the Soviets since the 1930s, his confession was littered with lies and evasions – including a false claim that he had broken off contacts with the KGB in 1946 after the Second World War. In fact, he had never stopped working for the Russians.

Meeting for a second time, Philby told Elliott: “I really did feel a tremendous loyalty to MI6, I was treated very, very well in it and I made some really marvellous friends there. But the over-ruling inspiration was the other side.”

He also claimed that his change of heart had been due to the advent of Clement Attlee’s Labour government, which had brought in many of the things he believed in, and that confessing had been a “tremendous relief”.