This story was originally published by Global Press Journal. Global Press Journal is an award-winning international news publication with more than 40 independent news bureaus across Africa, Asia and Latin America.

When Thomas Chiu Palomeque saw on social media that there was a shortage of hormone-replacement testosterone in Mexico City, he prayed that it wouldn’t affect his home state of Chiapas. Chiu Palomeque, who lives in the municipality of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, had recently begun taking testosterone to help transition from female, the sex he was assigned at birth, to male.

“One day, I wrote to all my friends that there aren’t any hormones left at the pharmacy downtown,” he says. “I told them I would go and check another one and, I was like ‘Phew! They have it here. Yes! Come and get it here.’”

But eventually, what Chiu Palomeque feared happened, and he ran out of testosterone drugs. The first time he missed a dose, his menstruation came back. It was a heavier flow and more painful than before he began hormone-replacement therapy.

“It’s as if knives are stabbing into my stomach,” Chiu Palomeque says.

Low-cost testosterone, a drug trans men and transmasculine people use for hormone replacement therapy, has been in short supply since 2020, forcing patients across Mexico to either spend more money or suspend treatment. According to the Cero Desabasto collective, an umbrella group of patient and doctors’ organizations that monitors medication shortages, patients around the country have reported a shortage of 250-milligram testosterone enanthate, which public hospitals provide to trans people and is the cheapest for people who don’t qualify to get it for free. Those who do qualify to get it for free still depend on this source because they don’t know about the free program or are wary of using a government service to obtain it.

The shortage of affordable testosterone has set back the physical and physiological advances that trans men and transmasculine people have made in their treatment. They include breast development, eliminating the menstrual cycle, voice change, and facial and body hair growth.

There are four medications—Sostenon 250, Lowtiyel, Nebido and Primoteston Depot—authorized for sale in the country. The medications are primarily produced to treat male hypogonadism, low or no testosterone production that occurs only in cisgender men, and are not necessarily intended for hormone replacement therapy, although they are authorized for that purpose.

The shortage of Primoteston Depot, the most affordable of the drugs, is largely due to supply chain disruptions related to the coronavirus pandemic. In a July statement, Bayer, the manufacturer of Primoteston Depot, said the disruptions had reduced the company’s ability to supply the drug not only in Mexico but across Latin America and worldwide.

Dr. Daniela Muñoz Jiménez, a physician and the founder of Trans Salud, a community health organization serving trans people, says discontinuing testosterone use for people who have had a hystero-oophorectomy, hysterectomy or oophorectomy, which involve the removal of the uterus and/or ovaries, is very different from stopping when one has ovaries and a uterus.

“It becomes catastrophic,” Muñoz Jiménez says.

Muñoz Jiménez says interruption of hormone therapy when one has ovaries can cause psycho-emotional health problems so severe that it leads some patients to take desperate measures like purchasing fake testosterone. Even for people who have had their wombs and ovaries removed, discontinuing the use of hormones can lead to problems at the metabolic level because the risk of decalcification, the loss of bone calcium, is extremely high, she says.

“It would be akin to starting andropause or menopause early,” Muñoz Jiménez says. “It is advancing a health process and can have a negative effect on the health of bones.”

For Muñoz Jiménez, this means that an important component of human health, which is happiness and wholeness, is collapsing.

If a testosterone injection is not taken as scheduled, drastic changes in cholesterol, triglycerides, blood pressure and glucose can occur within days, says Yusett Zárate Vidal, a psychotherapist from Tuxtla Gutiérrez, the capital of Chiapas.

The possibility of restarting menstruation has been terrifying for Sony Rangel, who, along with two other activists, founded Transmasculinidades MX, a group that offers people support services in the transition process. He dreads menstruation because of the disagreeable sensation he gets when he sees blood. Even the blood from a small cut gives him a feeling so unpleasant he cannot describe it.

“At some point, I’m also going to run out of medicine, and to be very honest with you, it really terrifies me,” Rangel says.

Rangel says some trans men seek hormone therapy with testosterone to relieve dysphoria and help build an image closer to their identity. Others opt for surgeries to remove breast tissue, the uterus or ovaries. Since gender identity is independent of sexual orientation, a trans man can be heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual or pansexual, among others, Rangel says. Some people assigned female at birth also do not identify as male and yet identify as trans people whose masculinity is predominant; the term “transmasculine” encompasses binary and nonbinary experiences.

In July, Transmasculinidades MX opened a dialogue with Mexico City’s Ministry of Health to find solutions to the shortage. They teamed with another advocacy group, La Jauría Trans, and sent a letter to the director of the Clínica Especializada Condesa, a public clinic that provides free medical services and medications, including testosterone, to trans people in Mexico City. In the letter, they described the consequences and risks the testosterone shortage poses to trans people. In July, the director of Condesa met with Transmasculinidades MX to tell them that the clinic had obtained 1,500 doses of testosterone, which would guarantee treatments for at least one month.

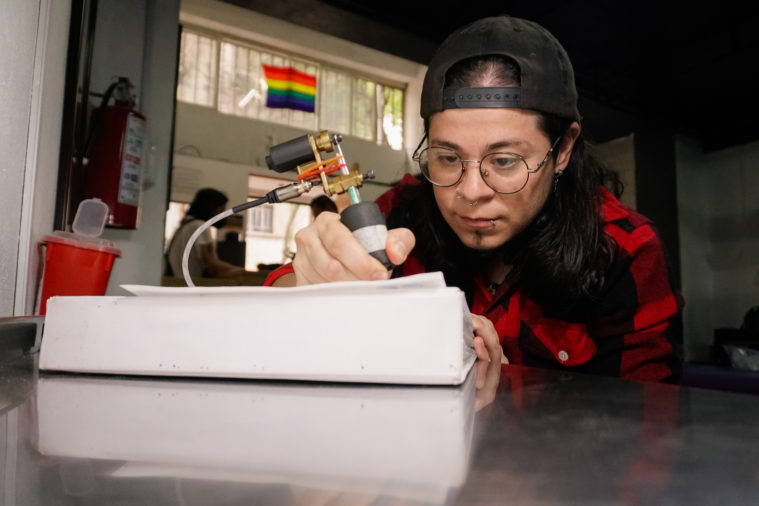

The last meeting between Transmasculinidades MX and the medical staff of the Condesa clinic was held in August, and it was also attended by the Comisión Federal para la Protección contra Riesgos Sanitarios, a government agency that oversees the approval of permits for medicines to be marketed in Mexico and alerts about counterfeit drugs. At that meeting, the agency launched a campaign to warn about counterfeit testosterone.

“I am very scared, but I am also very committed to finding alternatives that help all of us, not just me,” Rangel says.

“I am very scared, but I am also very committed to finding alternatives that help all of us, not just me.”

While Transmasculinidades MX is maintaining active communication with Mexico City’s Ministry of Health to permanently resolve the shortage, they are also organizing so that, along with professional psycho-emotional support, they can offer palliative measures during periods when hormone treatments are stopped or when advances are reversed, Rangel says. One such measure is physical training. Through online exercise routines, a specialized trans trainer works with each person on their dysphoria and dysmorphia. Another measure is a directory of civil associations nationwide, including peer groups that provide support and feature active listening and communication.

Global Press reached out to the Clínica Especializada Condesa and the Ministry of Health for comment and did not receive a response.

Testosterone-based medicine is also very expensive. The cheapest, Primoteston Depot, can cost up to 189 Mexican pesos (about $10) a month, and Nebido as much as 2,000 pesos ($103) monthly, Rangel says. He does not have health insurance, but he receives treatment for free at Condesa. Treatment is often unaffordable because securing a fixed income or formal employment is challenging among the trans population in Mexico. From a very young age, people in the trans community are often at higher risk of dropping out of school due to violence, stigma and homelessness. Compared with trans women, trans men and transmasculine people tend to have lower levels of education because trans women often start their transition at an older age, Rangel says.

Chiu Palomeque and Zárate Vidal, the psychotherapist, don’t have social security, so they work and buy their medicine at pharmacies. But the shortage has led to higher costs because they have had to switch to more expensive options. Zárate Vidal says it used to cost 150 pesos (about $7.75) per dose, but when that brand became unavailable, he switched to one that costs 600 pesos (about $31).

“And I know of many friends who have stopped using testosterone because they can’t afford it,” Zárate Vidal says. “In fact, I couldn’t find it here in Tuxtla or San Cristóbal. I spoke to a cousin who lives in Huixtla [another Chiapas municipality] and asked her to look for it and buy it for me.”

Chiu Palomeque continues to deal with the consequences of the shortage. He constantly worries about the possibility of going back to buying sanitary pads monthly. Because it had been so long since he’d had a period, it has become harder to predict, which makes him anxious. He tries hard to figure out how to supply himself with the medicine he needs to realize his true identity.

“It’s about finding the cheapest,” Chiu Palomeque says, “but that can be the riskiest.”