We talk about mental health more than ever, but the language we should use remains a vexed issue.

Should we call people who seek help patients, clients or consumers? Should we use “person-first” expressions such as person with autism or “identity-first” expressions like autistic person? Should we apply or avoid diagnostic labels?

These questions often stir up strong feelings. Some people feel that patient implies being passive and subordinate. Others think consumer is too transactional, as if seeking help is like buying a new refrigerator.

Advocates of person-first language argue people shouldn’t be defined by their conditions. Proponents of identity-first language counter that these conditions can be sources of meaning and belonging.

Avid users of diagnostic terms see them as useful descriptors. Critics worry that diagnostic labels can box people in and misrepresent their problems as pathologies.

Underlying many of these disagreements are concerns about stigma and the medicalisation of suffering. Ideally the language we use should not cast people who experience distress as defective or shameful, or frame everyday problems of living in psychiatric terms.

Our new research, published in the journal PLOS Mental Health, examines how the language of distress has evolved over nearly 80 years. Here’s what we found.

Generic terms for the class of conditions

Generic terms – such as mental illness, psychiatric disorder or psychological problem – have largely escaped attention in debates about the language of mental ill health. These terms refer to mental health conditions as a class.

Many terms are currently in circulation, each an adjective followed by a noun. Popular adjectives include mental, mental health, psychiatric and psychological, and common nouns include condition, disease, disorder, disturbance, illness, and problem. Readers can encounter every combination.

These terms and their components differ in their connotations. Disease and illness sound the most medical, whereas condition, disturbance and problem need not relate to health. Mental implies a direct contrast with physical, whereas psychiatric implicates a medical specialty.

Mental health problem, a recently emerging term, is arguably the least pathologising. It implies that something is to be solved rather than treated, makes no direct reference to medicine, and carries the positive connotations of health rather than the negative connotation of illness or disease.

Arguably, this development points to what cognitive scientist Steven Pinker calls the “euphemism treadmill”, the tendency for language to evolve new terms to escape (at least temporarily) the offensive connotations of those they replace.

English linguist Hazel Price argues that mental health has increasingly come to replace mental illness to avoid the stigma associated with that term.

How has usage changed over time?

In the PLOS Mental Health paper, we examine historical changes in the popularity of 24 generic terms: every combination of the nouns and adjectives listed above.

We explore the frequency with which each term appears from 1940 to 2019 in two massive text data sets representing books in English and diverse American English sources, respectively. The findings are very similar in both data sets.

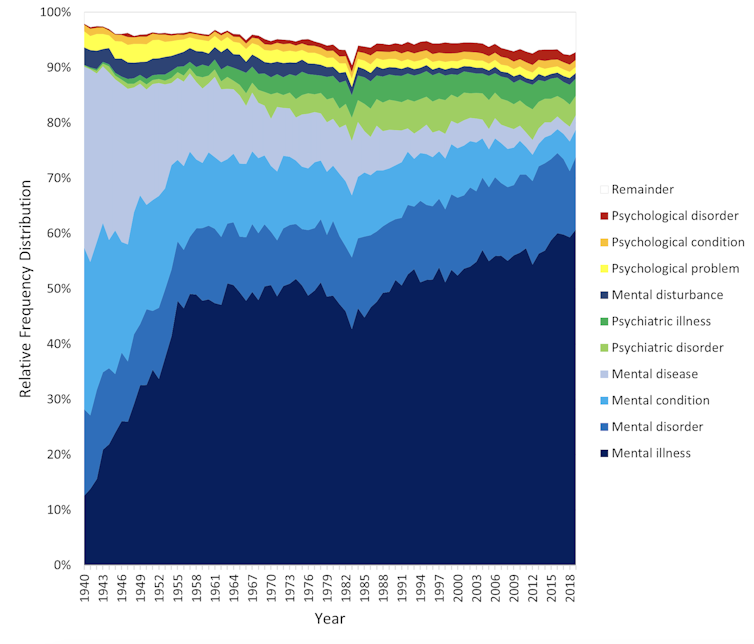

The figure presents the relative popularity of the top ten terms in the larger data set (Google Books). The 14 least popular terms are combined into the remainder.

Several trends appear. Mental has consistently been the most popular adjective component of the generic terms. Mental health has become more popular in recent years but is still rarely used.

Among nouns, disease has become less widely used while illness has become dominant. Although disorder is the official term in psychiatric classifications, it has not been broadly adopted in public discourse.

Since 1940, mental illness has clearly become the preferred generic term. Although an assortment of alternatives have emerged, it has steadily risen in popularity.

Does it matter?

Our study documents striking shifts in the popularity of generic terms, but do these changes matter? The answer may be: not much.

One study found people think mental disorder, mental illness and mental health problem refer to essentially identical phenomena.

Other studies indicate that labelling a person as having a mental disease, mental disorder, mental health problem, mental illness or psychological disorder makes no difference to people’s attitudes toward them.

We don’t yet know if there are other implications of using different generic terms, but the evidence to date suggests they are minimal.

Is ‘distress’ any better?

Recently, some writers have promoted distress as an alternative to traditional generic terms. It lacks medical connotations and emphasises the person’s subjective experience rather than whether they fit an official diagnosis.

Distress appears 65 times in the 2022 Victorian Mental Health and Wellbeing Act, usually in the expression “mental illness or psychological distress”. By implication, distress is a broad concept akin to but not synonymous with mental ill health.

But is distress destigmatising, as it was intended to be? Apparently not. According to one study, it was more stigmatising than its alternatives. The term may turn us away from other people’s suffering by amplifying it.

So what should we call it?

Mental illness is easily the most popular generic term and its popularity has been rising. Research indicates different terms have little or no effect on stigma and some terms intended to destigmatise may backfire.

We suggest that mental illness should be embraced and the proliferation of alternative terms such as mental health problem, which breed confusion, should end.

Critics might argue mental illness imposes a medical frame. Philosopher Zsuzsanna Chappell disagrees. Illness, she argues, refers to subjective first-person experience, not to an objective, third-person pathology, like disease.

Properly understood, the concept of illness centres the individual and their connections. “When I identify my suffering as illness-like,” Chappell writes, “I wish to lay claim to a caring interpersonal relationship.”

As generic terms go, mental illness is a healthy option.

Nick Haslam receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Naomi Baes receives funding from the Australian Government (Research Training Program Scholarship).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.