The sex of human and other mammal babies is decided by a male-determining gene on the Y chromosome. But the human Y chromosome is degenerating and may disappear in a few million years, leading to our extinction unless we evolve a new sex gene.

The good news is two branches of rodents have already lost their Y chromosome and have lived to tell the tale.

A new paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science shows how the spiny rat has evolved a new male-determining gene.

How the Y chromosome determines human sex

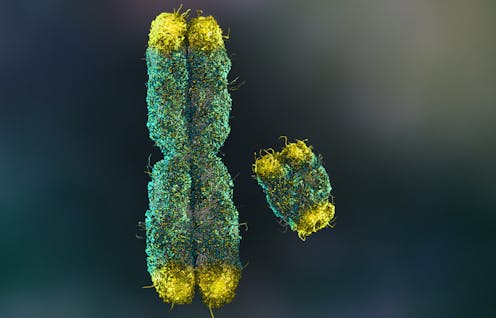

In humans, as in other mammals, females have two X chromosomes and males have a single X and a puny little chromosome called Y. The names have nothing to do with their shape; the X stood for “unknown”.

The X contains about 900 genes that do all sorts of jobs unrelated to sex. But the Y contains few genes (about 55) and a lot of non-coding DNA – simple repetitive DNA that doesn’t seem to do anything.

But the Y chromosome packs a punch because it contains an all-important gene that kick-starts male development in the embryo. At about 12 weeks after conception, this master gene switches on others that regulate the development of a testis. The embryonic testis makes male hormones (testosterone and its derivatives), which ensures the baby develops as a boy.

This master sex gene was identified as SRY (sex region on the Y) in 1990. It works by triggering a genetic pathway starting with a gene called SOX9 which is key for male determination in all vertebrates, although it does not lie on sex chromosomes.

The disappearing Y

Most mammals have an X and Y chromosome similar to ours; an X with lots of genes, and a Y with SRY plus a few others. This system comes with problems because of the unequal dosage of X genes in males and females.

How did such a weird system evolve? The surprising finding is that Australia’s platypus has completely different sex chromosomes, more like those of birds.

In platypus, the XY pair is just an ordinary chromosome, with two equal members. This suggests the mammal X and Y were an ordinary pair of chromosomes not that long ago.

In turn, this must mean the Y chromosome has lost 900–55 active genes over the 166 million years that humans and platypus have been evolving separately. That’s a loss of about five genes per million years. At this rate, the last 55 genes will be gone in 11 million years.

Our claim of the imminent demise of the human Y created a furore, and to this day there are claims and counterclaims about the expected lifetime of our Y chromosome – estimates between infinity and a few thousand years

Rodents with no Y chromosome

The good news is we know of two rodent lineages that have already lost their Y chromosome – and are still surviving.

The mole voles of eastern Europe and the spiny rats of Japan each boast some species in which the Y chromosome, and SRY, have completely disappeared. The X chromosome remains, in a single or double dose in both sexes.

Although it’s not yet clear how the mole voles determine sex without the SRY gene, a team led by Hokkaido University biologist Asato Kuroiwa has had more luck with the spiny rat – a group of three species on different Japanese islands, all endangered.

Kuroiwa’s team discovered most of the genes on the Y of spiny rats had been relocated to other chromosomes. But she found no sign of SRY, nor the gene that substitutes for it.

Now at last they have published a successful identification in PNAS. The team found sequences that were in the genomes of males but not females, then refined these and tested for the sequence on every individual rat.

What they discovered was a tiny difference near the key sex gene SOX9, on chromosome 3 of the spiny rat. A small duplication (only 17,000 base pairs out of more than 3 billion) was present in all males and no females.

They suggest this small bit of duplicated DNA contains the switch that normally turns on SOX9 in response to SRY. When they introduced this duplication into mice, they found that it boosts SOX9 activity, so the change could allow SOX9 to work without SRY.

What this means for the future of men

The imminent – evolutionarily speaking – disappearance of the human Y chromosome has elicited speculation about our future.

Some lizards and snakes are female-only species and can make eggs out of their own genes via what’s known as parthenogenesis. But this can’t happen in humans or other mammals because we have at least 30 crucial “imprinted” genes that work only if they come from the father via sperm.

Read more: What we learn from a fish that can change sex in just 10 days

To reproduce, we need sperm and we need men, meaning that the end of the Y chromosome could herald the extinction of the human race.

The new finding supports an alternative possibility – that humans can evolve a new sex determining gene. Phew!

However, evolution of a new sex determining gene comes with risks. What if more than one new system evolves in different parts of the world?

A “war” of the sex genes could lead to the separation of new species, which is exactly what has happened with mole voles and spiny rats.

So, if someone visited Earth in 11 million years, they might find no humans – or several different human species, kept apart by their different sex determination systems.

Read more: Did sex drive mammal evolution? How one species can become two

Jenny Graves receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.