In the years running up to the fatal beating of Tyre Nichols, the Memphis Police Department faced an increasingly dire staffing crisis. Indeed, shortages on the force have led to questions over whether, given their relative lack of experience, the five officers now charged with Nichols’ murder would have been assigned to the now-disbanded SCORPION unit – or even hired in the first place.

Memphis isn’t alone in confronting the issue of dwindling officer numbers. In January 2023, the federal judge monitoring the Baltimore Police Department said a severe staffing shortage there is causing slow reform progress as the agency attempts to comply with a federal consent decree.

We are criminologists, two with experience as police officers, who study police turnover and its effects on agencies and communities. In jurisdictions across the U.S., we’ve seen how police departments are experiencing significant changes to the three main variables in police staffing: recruitment, resignations and retirements.

We’ve also seen that these changes are likely to deteriorate the quality of policing and may give rise to more incidents of officer misconduct, increased violent crime, decreased policing services and a failure to meet community and professional standards. The investigation into what happened in Memphis, Tennessee, on Jan. 7 is still ongoing, but we believe the effect of staff shortages and the experience levels of the officers involved in Nichols’ death should form part of the inquiry.

Turnover in Memphis

Since 2011, the earliest year of staffing data available on the Memphis Data Hub, the Memphis Police Department’s number of sworn officers has dropped by 22.6% – from a high of 2,449 officers in September 2011 to a low of 1,895 officers in December 2022.

When an agency loses this many officers, one consequence can be that more inexperienced officers end up in specialized details like SCORPION, as agencies struggle to fill gaps in their operations.

In response to staffing shortfalls and rising crime, the Memphis Police Department relaxed its hiring standards in 2018, such as by no longer requiring a college degree to begin working as a police officer.

However, this approach only temporarily improved staffing levels. After mass racial justice protests in the wake of the 2020 killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, the trend reversed as the agency began losing officers again. This downward trend surpassed the lows that previously led to lowered hiring standards in 2018.

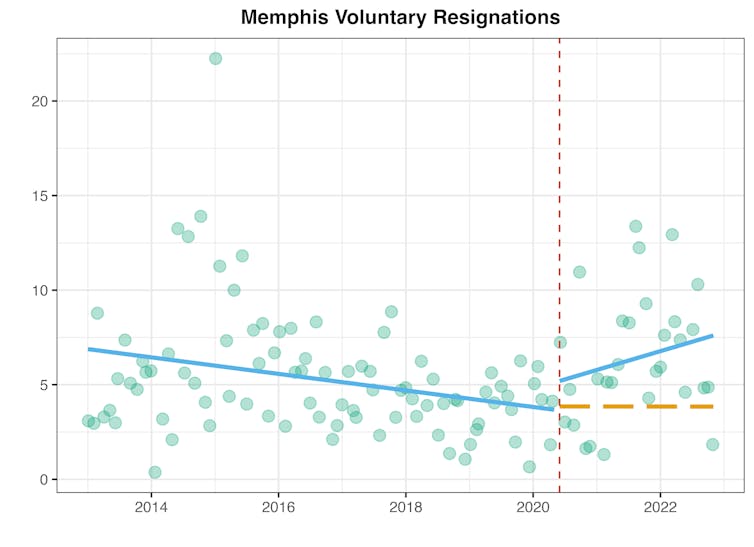

Turnover takes different forms, and in our analysis, the Memphis Police Department has seen a distinct increase in the number of officers leaving the agency voluntarily, prior to retirement. The department experienced a significant spike in resignations since the summer of 2020, losing an additional 75 officers to resignations compared with what would have been expected based on trends in years past. This increase in resignations equates to an additional 3.3% of the Memphis Police Department leaving in just two years.

A national trend

Concern about staffing shortages is not confined to Memphis and Baltimore. Over the past three years, police recruitment and retention have been key concerns for jurisdictions across the country.

We monitor police staffing levels in several agencies across the U.S. In one large, Western police department, we found that in the seven months following the Floyd protests, voluntary resignations of sworn officers were nearly three times (279%) higher than baseline expectations.

In some places, extreme staffing pressure has led to rapid increases in police response times to emergencies. For example, in Salt Lake City, the police staffing crisis led to response times nearly doubling for priority calls in 2020 and 2021.

In conversations with police chiefs and other leaders at smaller and suburban agencies, we hear that they have faced a lower-intensity staffing challenge for more than a decade.

However, those at larger, metropolitan agencies nationwide say the crisis has boiled over, and they fear they are losing the ability to provide baseline levels of service. Both groups of police executives directly link the staffing crisis to fallout from the 2020 George Floyd protests.

Transfers, retirements and $30,000 bonuses

Although our studies do not follow individual officers, recent reporting by The Marshall Project uses yearly federal economic data to show that nationally the police profession experienced a small decline in total employees – including both sworn officers and civilian staff – between March 2020 and August 2022.

This may reflect agencies offering highly lucrative bonuses for officers willing to transfer agencies, rather than swarms of officers leaving the profession altogether.

When speaking with police chiefs in large agencies, a consistent story emerges: They say officers are not leaving the profession, but instead are leaving for other nearby agencies that offer better pay and a more positive work environment.

This phenomenon, known as “lateral transfers,” is rapidly shifting officers away from large, urban departments and toward smaller police agencies and sheriff’s departments.

In an ongoing study, we analyze turnover data from 14 large agencies over the last decade and observe that one suburban agency and one sheriff’s department actually experienced decreases in resignations and retirements during the period. Meanwhile, the large urban departments in our sample generally experienced surges in resignations and retirements since the summer of 2020, indicating there are turnover patterns that benefit some agencies, while harming others.

It makes economic sense for agencies to compete for already trained officers. Turnover is expensive. Hiring and training a new officer can cost one to five times the annual salary of an individual officer.

Agencies can save on these costs by competing for already trained officers, as they have already passed background checks and committed to the profession to some degree. Severe labor shortages have resulted in agencies turning to lateral bonuses, offering large financial benefits to attract already certified officers from other agencies. The Seattle and New Orleans police departments now offer $30,000 bonuses to attract trained officers.

The police staffing crisis has been exacerbated by the ongoing retirement wave of officers hired through funding from the 1994 crime bill. The bill, led by then-Senator Joe Biden, directed over $8 billion to hiring an additional 100,000 police officers nationwide in order to combat crime. However, officers hired with that federal money are now retiring, adding additional staffing pressure as the most experienced officers leave the profession in the same wave that brought them in.

Focus on public safety

The International Association of Chiefs of Police surveyed its members in 2019 and found that 75% were experiencing greater recruitment challenges, with 25% reducing or eliminating some services as a result.

Read more: Tyre Nichols' death underscores the troubled history of specialized police units

Good policing requires good police officers. To live up to community expectations and fulfill the general policing mission of improving public safety, we believe local leaders need to adequately staff their police agencies so that under-policing does not continue to negatively impact the communities they serve.

Because staffing shortages involve agencies across the nation, and in many cases pit agencies against one another in competition for ever-decreasing pools of talent, it will likely require federal and state action to address effectively. President Biden has proposed $10.9 billion to help hire an additional 100,000 police officers over the next five years. Adding more officers will help, but so too will keeping officers in the profession, especially in the communities most impacted by historic increases in violent crime.

Addressing this issue will require the collaboration of police leaders and their communities to determine what level of police services they require, as well as financial support from state and federal levels to ensure police agencies can improve, rather than degrade, their workforces.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.