A court in Texas has granted a stay of execution for Melissa Lucio, who was convicted of murdering her two-year-old daughter, after new evidence emerged.

Lucio was set to be executed by lethal injection on Wednesday, and would have become the first Hispanic woman to be put to death in Texas. However, the appeals court on Monday granted a request by Lucio’s lawyers to delay the execution so a lower court can review her claims that new evidence would exonerate her.

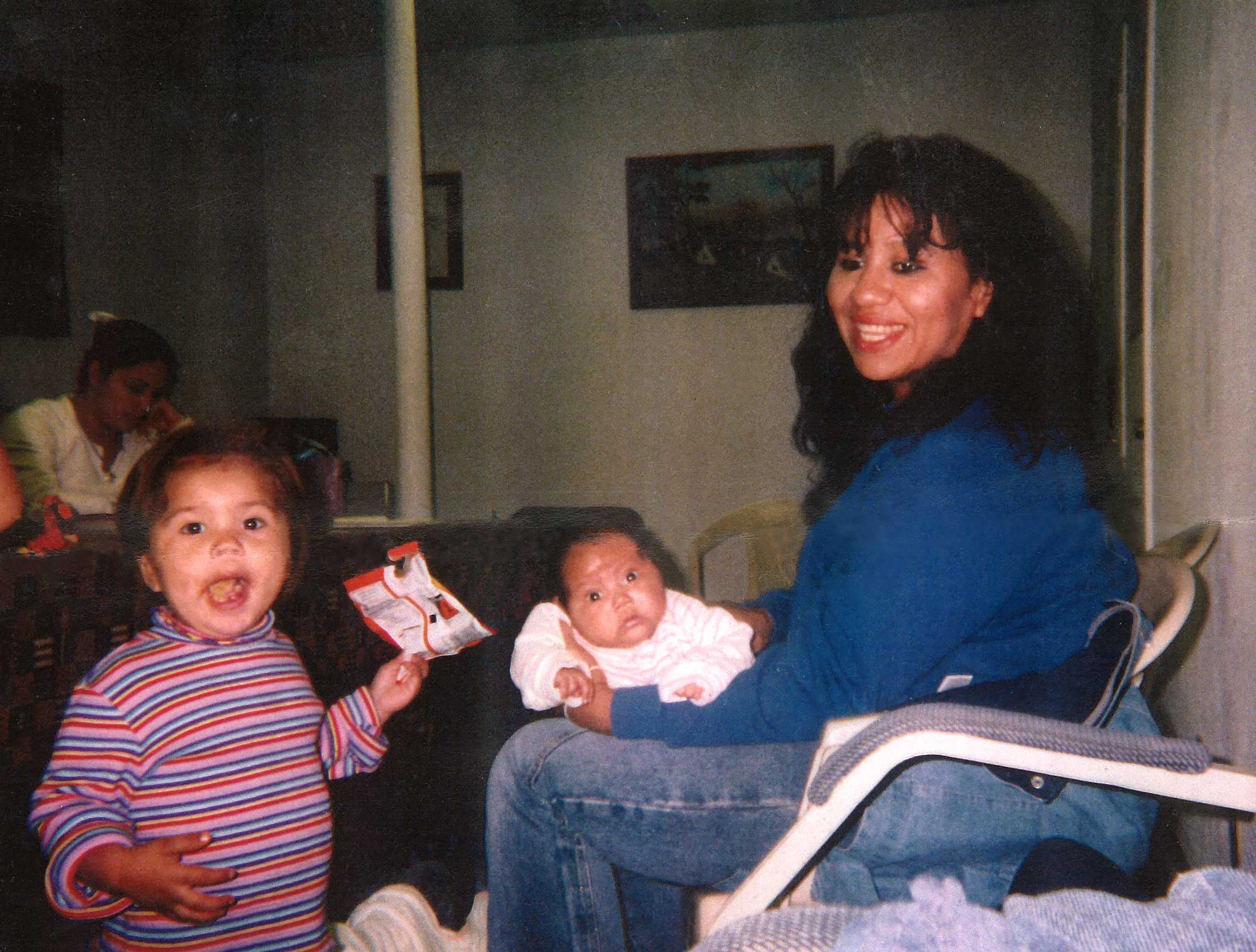

Prosecutors have maintained that Lucio abused her daughter, Mariah, leading to her death in 2007. Her lawyers have maintained the child died from injuries she sustained falling down a steep flight of stairs.

“I am grateful the court has given me the chance to live and prove my innocence,” Lucio said in a statement provided by the Innocence Project, whose lawyers are helping defend her. “Mariah is in my heart today and always.”

The effort to stay the execution has gained national attention and support from celebrities, as well as a bipartisan coalition in the Texas legislature.

Lucio’s lawyers have focused on a confession they say was coerced and unreliable, the result of relentless questioning and her long history of being sexually, physically and emotionally abused.

They argue that Lucio was not allowed to present evidence questioning the validity of her confession.

Her lawyers also contend that unscientific and false evidence misled jurors into believing Mariah’s injuries could have been caused only by abuse and not by medical complications from a severe fall.

Lucio’s lawyers have since presented new evidence from forensic experts who argue the child died from blunt-force trauma to her head that was consistent with injuries she could have sustained in falling down a flight of stairs two days before her death as the family was moving.

“It would have shocked the public’s conscience for Melissa to be put to death based on false and incomplete medical evidence for a crime that never even happened,” said Vanessa Potkin, one of Lucio’s lawyers with the Innocence Project.

“All of the new evidence of her innocence has never before been considered by any court. The court’s stay allows us to continue fighting alongside Melissa to overturn her wrongful conviction.”

Cameron County District Attorney Luis Saenz, who was not in office when Lucio was tried, said he welcomed “the opportunity to prosecute this case in the courtroom: where witnesses testify under oath, where witnesses may be cross-examined, where evidence is governed by the rules of evidence and criminal procedure”.

In a previous Texas House committee hearing, Saenz had said he disagreed with Lucio’s lawyers’ claims that new evidence would lead to an exoneration.

In its three-page order, the appeals court asked that the trial court in Brownsville that handled Lucio’s case review four claims her lawyers have made: whether prosecutors used false evidence to convict her; whether previously unavailable scientific evidence would have prevented her conviction; whether she is actually innocent; and whether prosecutors suppressed evidence that would have been favourable to her defence.

It was not immediately clear when that review would begin.

The execution stay was announced minutes before the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles had been set to consider Lucio’s clemency application to either commute her death sentence or grant her a 120-day reprieve. The paroles board did not review her clemency petition because of the execution stay.

If the case were to come back before the board in the future, Lucio’s lawyers would have to file a new petition.

Texas has far outpaced other US states in the number of people executed since 1976, with 574 people put to death by state authorities in the years since.