Review: Vivienne Binns: On and through the Surface, MUMA

In 1967, Vivienne Binns blasted onto the art scene with her Vag Dens and Phallic Monuments work at Watters Gallery, Sydney.

The show was universally slammed by the artworld for its provocative and sexual imagery, which, according to art critic Elwyn Lynn “affronts masculinity”.

More than five decades later, we read these works differently.

On entering MUMA, we are blasted by the visual power of her paintings that employed Surrealist, Dadaist and graphic styles to address gender, sexuality and portraiture.

On the other side of the room, a kinetic sculpture, Suggon (1966), is embellished with a pulsating metal scourer suggesting a smile that doubles as a muff of pubic hairs.

The riot of colour and mocking sexuality in these works asserts a bold and confident rebuttal to the male gaze and male entitlement. In the current discourse of women being told off for failing to smile, the room seems to be shouting, “up yours!”

Read more: Beauty and audacity: Know My Name presents a new, female story of Australian art

Pioneering and transgressive

A survey of Vivienne Binns’ comprehensive legacy and lifetime of breaking art’s institutional rules is long overdue.

Binns has innovated in overlapping fields of community, collaborative, feminist and conceptually based art since the late 1960s, an era that reevaluated womanhood and sexuality.

After offending the sensibilities of so many at her first exhibition, Binns continued to disregard the orthodoxies of the established art world by working with non-artists, pursuing the belief creativity was a realm for everybody to explore.

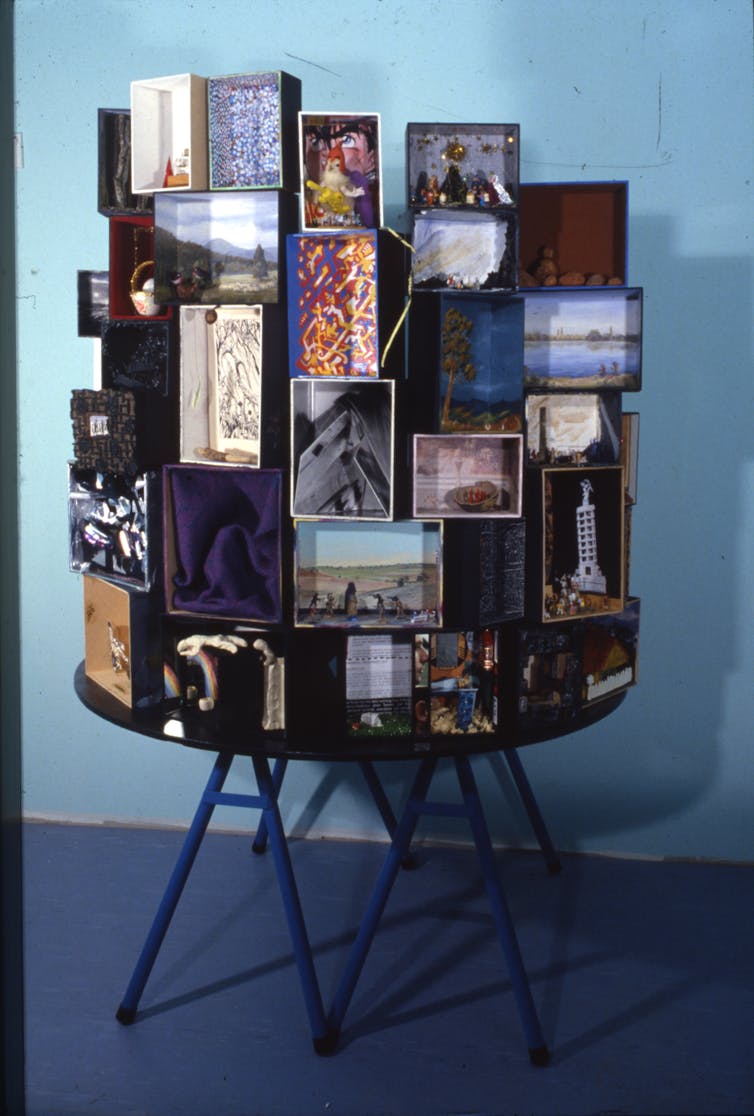

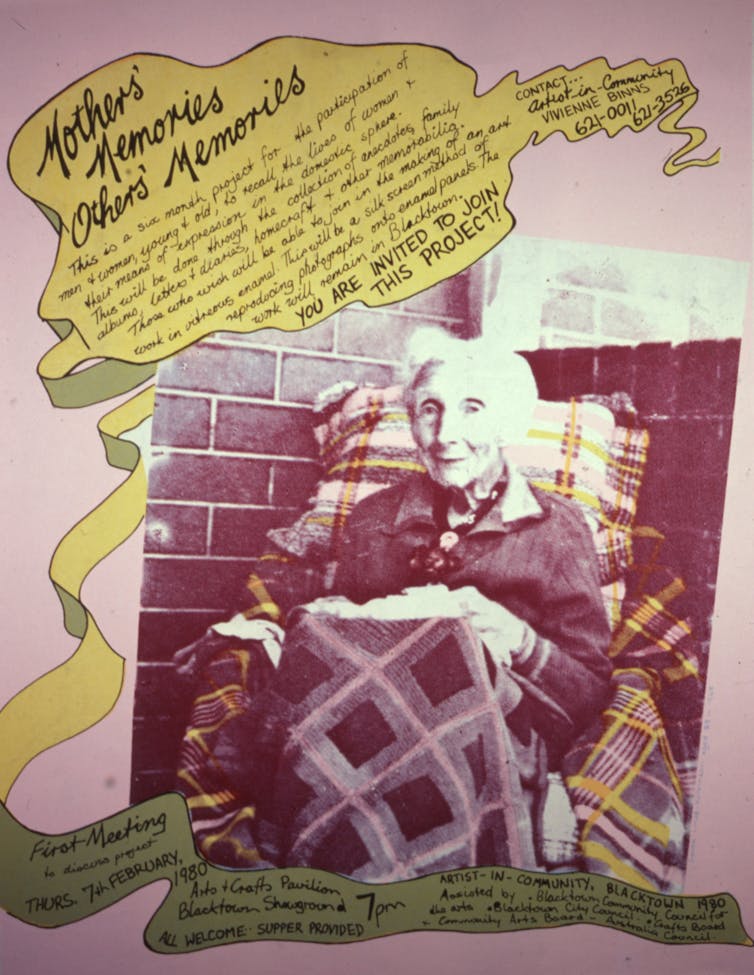

During this time, spanning from 1970s to the early 80s, her most notable collaborative project was Mother’s memories, other’s memories (1979-81), conceived to reinterpret “memories drawn from anecdotes, letters, diaries handcrafts, photos from family albums”.

Presented in a postcard carousel, the content, aesthetics and sensibility of the screenprinted postcard broke new ground at time when women’s experiences mainly went undervalued, unobserved and undocumented.

While working on Mother’s memories, other’s memories, Binns also recorded her own mother’s memories in a work called Self-portrait self-image 1980, which consists of an interview and a two-channel slide show, one depicting the life of Joyce Binns, and the other revealing corresponding years in Vivienne’s life.

Art is a human activity

When Vivienne Binns returned to the studio in 1984 she established a painting practice that ignored all institutional orthodoxies.

Instead of pursuing more conventional concerns such as material, style and aesthetics, her work is driven by processes formed over many years doing community projects.

Binns says she uses art to work out how to be in the world, and describes these central tenets as processes and relationships that focus on “how things fit together”.

Over nearly 40 years, this approach has been the catalyst for many bodies of work that explore how art and life can intersect.

Binns’ unflinching commitment to stay true to her process-driven methods has meant her wayward practice is difficult to classify and commodify. Throughout her career she has regularly discovered the boundaries of permission to be experimental.

The second part of this exhibition is dedicated to Binns’ painting. The show elegantly and thematically plots her eclectic styles and her enduring interest in the domestic and the work of women.

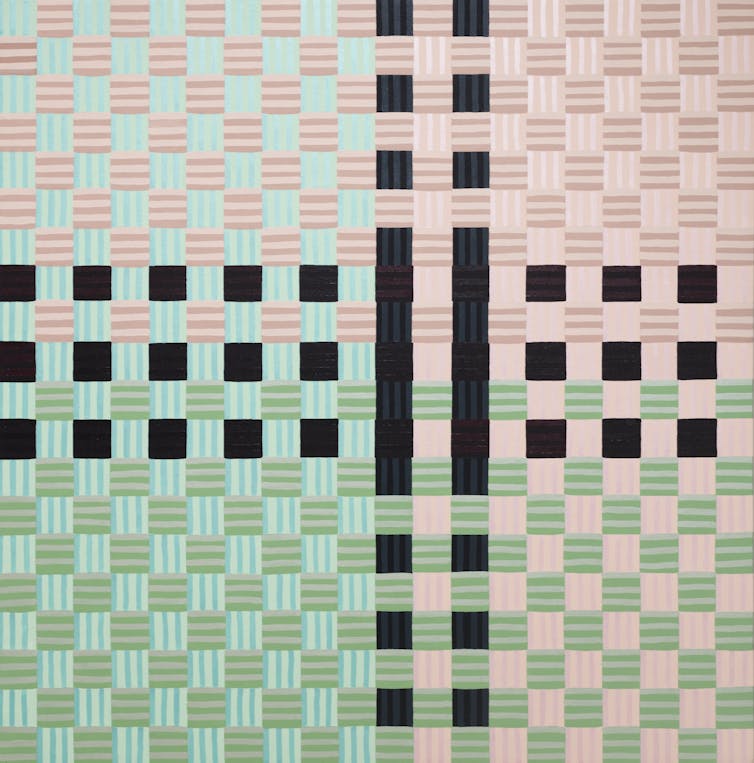

She uses design elements, decoration, textiles, fabric, fragments, surfaces and layering to further the idea that art is a human activity not just reserved for artists.

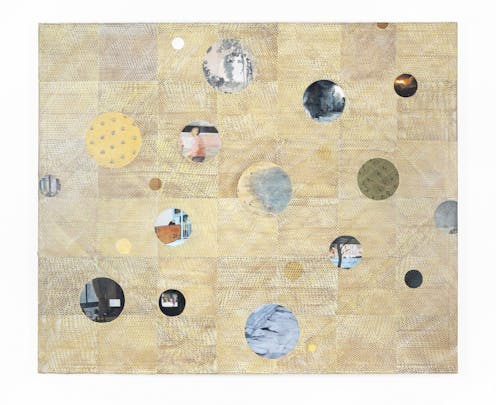

Bodies of work, such as Memory of the Unknown Artist and Others (1996-), link to her reinterpretations of women’s creative pursuits in the making of tapas, or weavings she encountered during travels in the Pacific.

Binns’ preoccupation with women’s work and spaces are most evident in her ongoing project, the Unknown Artist series (1996-). Starting with a tablecloth that was given to her by a friend, Binns wanted to find a way to reference and remember the unknown creatives who produced these humble items.

In the act of repainting, Binns gets to know the makers through their decision-making processes, their cultural circumstances and their relationship with materials and mechanical processes.

In doing so, she draws our attention to the fact that art is everywhere.

Coming up close to these painted surfaces is one of the greatest pleasures of experiencing this show. Unassuming raised patterning techniques hold the eye, each one distinct in behaviour and makeup. Shifts in tone and contrasts in colour and the introduction of ever so subtle further layering of metallic paint, visually enhance and accelerate the affect of the works.

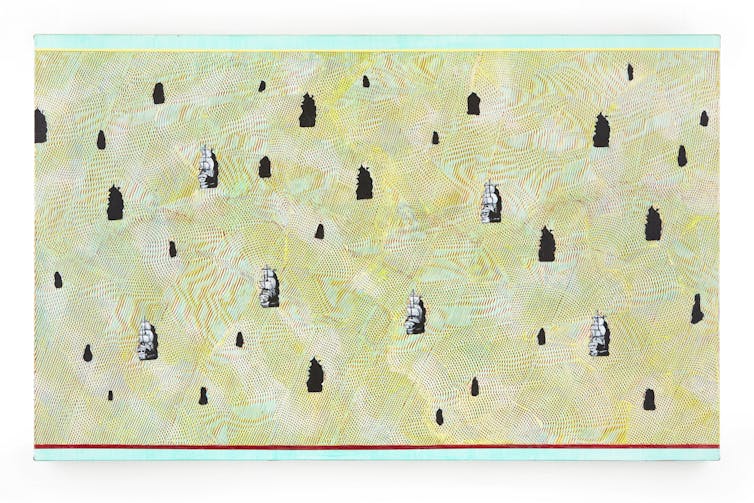

In later works the paint gets thicker. The patterns are wave-like furrows. They have an evenness of mechanical reproduction, but maintain the personality and fluidity of the handmade.

Three last works

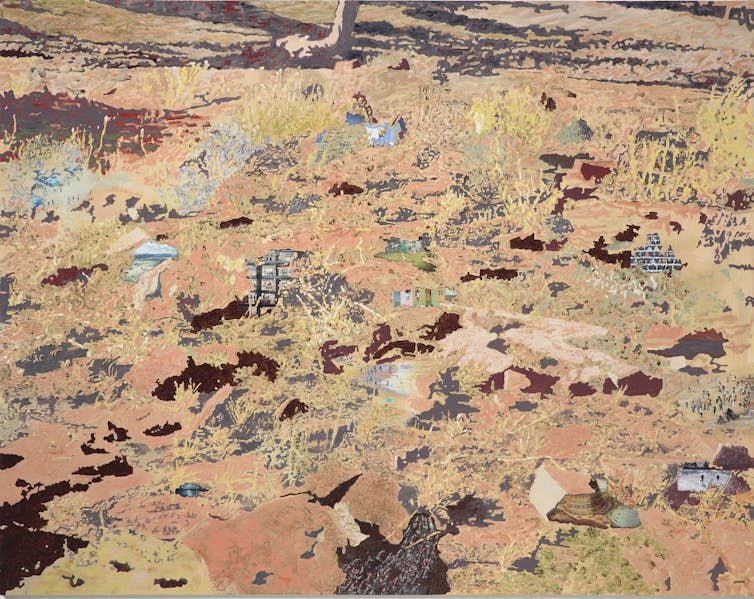

In Somebody’s everyday, somewhere, sometime (2008), Topographica (2009), and Minding clouds (2016), Binns returns to and extends concerns about place and land that started during a Pacific residency.

Stepping beyond the domestic, the artist’s signature motifs and complex layering of surface and pattern are applied liberally. Narrative vignettes of world events have been integrated or inserted.

These troubling outward looking works register a noticeable shift to the Binns’ preoccupation.

When Binns retired from teaching in 2012 she said her main job was:

to deal with the process of ageing, understanding that and coming to terms with death.

Binns is still using art to work out how to be in the world. In doing so, she engages us in the same questions.

Vivienne Binns: On and through the Surface is at MUMA, Melbourne, until April 14, then the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, from July 15 to September 25.

Julie Shiels does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.