The story of the British matchstick girls who in 1888 took strike action against the dominating, patriarchal world of matchstick making isn’t well known.

But these were the women who worked 14 hours a day in the East End of London and who were exposed to deadly phosphorous vapours on a daily basis.

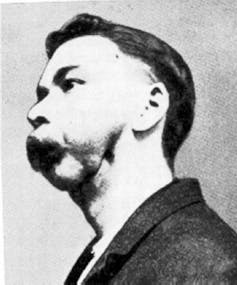

Working with white phosphorous – which was added to the tips of matches to enable a “strike anywhere effect” – was highly toxic and responsible for the devastating disease known as “phossy jaw”. This nickname was given by the match makers to the particularly nasty condition “phosphorous necrosis of the jaw”. The effect literally causing the jaw bone to rot.

Doctors soon began treating these women for the disease – which would often spread to the brain leading to a particularly painful and horrific death, unless the jaw was removed. And even then a prolonged life was not guaranteed.

But even though the risks were obvious, this was the Industrial Revolution – before employers were legally required to create safe working conditions. This meant that women on low wages continued to work long hours, while exposed to the toxic impact of white phosphorous and the devastating consequences this would have on their health.

Women’s rights

Many of these women were working at Bryant and May (which is unrelated to the current Bryant and May, which also makes matches) and were Irish immigrants. They lived in abject poverty, in filthy housing unfit for human habitation and were often subject to prolonged hours of backbreaking work making matches. But despite the incessant exploitation, the low pay and excessive fines issued simply for being late, dropping a match or talking to others, the workers were forced to continue to work in these oppressive conditions. Times, however, were changing.

Annie Besant, a well known socialist exposed the conditions within the factory in her article White Slavery in London. This infuriated the factory owners and they attempted to force the workers to sign a paper stating that they were happy with their working lives. The women refused to do this and following the sacking of one of their own, they decided to take action. By the end of the day, 1,400 women and girls were out on strike.

Ultimately, the matchstick girls saw all their demands achieved. Disappointingly, though, it wasn’t until 1906 – almost 20 years later – that white phosphorous was made illegal in the use of matchsticks. This eventually eliminated the disease in the UK. Similarly, in the US, the government chose to place a “punitive tax” on white phosphorus matches. And the tax was so high it made manufacturing them unrealistic.

Modern medicines

“Phossy jaw” was thought to have been eliminated through modern day working practices, but in a twist of fate, contemporary medicine has actually resurrected this disease. A group of drugs known as Bisphosphonates, commonly used in cancer treatment and to reduce the impact of bone thinning, has the potential to cause deterioration of the jaw.

With good oral care and dentistry, regular checks and antibiotic therapy, the risk is relatively low and treatment less radical. But it shows how the development of new and innovative ways of treating medical conditions – that improve and prolong life – can inadvertently create other problems.

The story of the plight of the matchstick girls and many women like them tells of the social injustices that prevailed throughout history. But disappointingly, such suffering continues to exist in society today.

Research shows hospital staff still continue to take women’s pain less seriously, compared with men’s pain. And that less time is spent treating women – who are more likely to be wrongly diagnosed.

Women in their defiance, continue to challenge health inequality and those who seek to oppress and exploit them not only nationally, but also globally. Women in their droves are standing up for other women – as can be seen in the recent outcry across the world over vaginal mesh implants. Women are no longer willing to accept poor health outcomes as an inevitability of their oppressed lives.

Today, we must continue to promote gender equality if our children and grandchildren are to have lives that are fulfilled and rewarding. To do this, we need to be as strong and courageous as the matchstick women to take action against the oppressive structures that continue to exist within a patriarchal society.

Catherine Kelsey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.