Sadie Dupuis was riding in a packed van through rural Montana, jostling around with her bandmates and their drum kit and merch boxes. She’d just learned that she had pneumonia after stopping at an urgent care clinic.

Speedy Ortiz, the rock band for which Dupuis is the songwriter and guitarist, was headed to play a show in Canada. After three months on the road for back-to-back tours, the group was exhausted. Dupuis had been trying to figure out why her nagging cough hadn’t cleared up, and had squeezed in visits to a handful of different clinics over several weeks to try to get an answer. She finally had one, but it didn’t change anything about her plans.

“I hadn't lost my voice; it didn't even occur to me to cancel shows. A lot of musicians my age and older came up in that ‘the show must go on’ tradition,” says Dupuis, who’s 35. The headliner on that tour had also come down with pneumonia, and hadn’t backed out of any stops. “We’d perform through anything unless we were physically unable,” she says. “It was the reality of how people worked.”

That was back in 2014. Dupuis doesn’t stand by that mentality anymore—and she hasn’t since the start of the pandemic, which shifted her perspective. When tours across the country were canceled to prevent the spread of Covid-19, she started meeting with other musicians to strategize how to help those who were suddenly out of work. Without a lot of options, many ended up back on stage, even at the risk of their own health. They needed the money. Conditions for musicians were—and had been—dire: low pay from concert halls and festivals hadn’t increased in decades, public arts funding was limited, venues took hefty cuts from merchandise profits, and streaming services provided meager profits.

Dupuis wanted to change that; to really shift how the finances of the music industry worked. But she found there was really nowhere to go with her concerns.

Unlike many sectors of the labor market, the vast majority of musicians have historically not had union representation. Artists are considered independent contractors running their own businesses, meaning they aren’t able to unionize in the same way as, say, factory workers at an auto plant or journalists at newspapers.

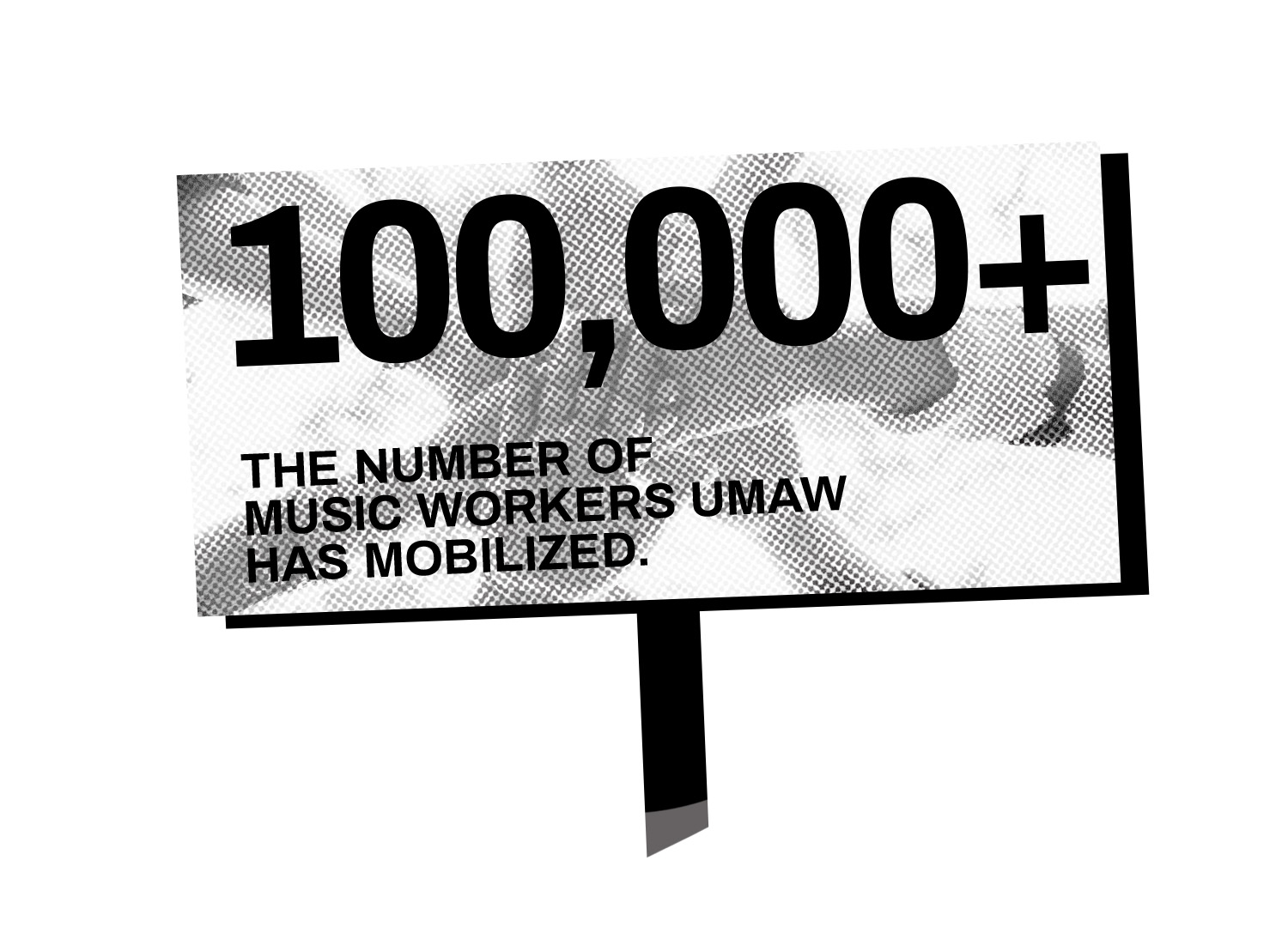

Dupuis believed that without a larger collective voice, artists would continue to struggle. And so, she—along with 14 other musicians—formed the United Musicians and Allied Workers (UMAW) group, an advocacy organization aimed at bringing music workers together to fight for a more just industry.

The group was announced publicly in May 2020. Since then, they’ve mobilized over 100,000 music workers, which includes not only musicians, but songwriters, venue staff, indie label employees, and booking agents. Members make a self-determined monthly dues payment of $3 to $15. They’ve opened local chapters in New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Philadelphia. A steering committee helps direct the group as a whole, and smaller groups focus on specific campaigns.

Most members are gig workers who only have the opportunity to make money from touring and streaming—neither of which pay fairly. “Opening bands fees haven't really changed in several decades. A lot of opening artists make $250 a night, and that might be split between a five-person band with a couple people on crew—the money disappears very quickly,” Dupuis says.

As ticket sales have stagnated and the costs of touring have continued to rise, even headlining musicians are struggling. “It’s insane how much they have to spend,” says Ari Fouriezos, an artist manager at Friendly Announcer, who works with bands like Big Thief and Caroline Rose. “They spend on a corporate level, but they don’t get the benefits of a corporation—no discounts, no leveraging, no unifying force showcasing that these bands are stimulating the economy.”

A group that Fouriezos works with headlines venues in the U.S. that hold as many as 1,800 people. On a recent 60-day tour, the five-piece band brought in about $320,000 (excluding merch sales), but their expenses were so high that they only walked away with $15,000 of profit. “These artists have a ton of touring history and did this for 10 years before starting to make these numbers,” Fouriezos says. “Every single cost goes back to the artist. There’s so little room for profit on top.”

Exorbitant ticket distributor fees are becoming cost-prohibitive for fans, shrinking concert attendance and making it less likely for those who do show to be able to buy merchandise, Fouriezos says.

There’s little control over how their music can be shared with audiences, too. When Universal Music Group decided to pull all of its artists' songs from TikTok during a licensing war earlier this year, it hurt small, indie artists the most, greatly limiting their chances of exposure to new fans and the virality that wins better record deals and touring opportunities these days.

Then there’s the threats from AI. Many artists are concerned with how large companies will use it to avoid hiring real people. This led UMAW to call on Congress to block big corporations from holding copyrights on music that’s created with significant AI-enabled elements, protecting jobs for actual humans. “You aren't going to go to your local club and see an AI band,” says Zack Nestel-Patt, an organizer with UMAW and bassist of the indie rock band No Swoon. “Where the issue lies is in the true workhorse of music industry finances, which is TV and movie scores. It will for sure replace my friends who make their money as composers writing for ads. Instead of a musician making money, now there's just more corporate profit.”

Despite the challenges, there have been wins. UMAW has been focused on raising artists’ wages, including calling for fair pay at SXSW, which hadn’t increased its rates in a decade. After a UMAW petition, the festival raised rates from $250 for bands and $100 for solo artists to $350 and $150, respectively. Still paltry, UMAW believes, but it’s progress.

Then there’s arguably the biggest issue plaguing the music industry right now: payouts from streaming. Currently, Spotify, Apple, Amazon, and Google pay an average of $0.00173 per stream—and a large percentage of that goes to the rights holders—typically labels—before an artist sees any money (if you can really see a fraction of a fraction of a cent).

“So many artists have been forced to not envision music as a career because of the finances,” Nestel-Patt says. “And that’s not to say you should make art to make money. I don't think anybody’s getting into music to do that. But you do have to pay rent, and it would be nice if more people could do that by making art and making beautiful things. You don't have to necessarily work other jobs on top of that if you envision a different way of finances flowing in the music industry.”

In the summer of 2021, UMAW turned their efforts toward public pressure, lobbying, and legislation. “We cold emailed a lot of Congress members to start conversations,” Nestel-Patt says. One member had worked with U.S. Representative Rashida Tlaib of Michigan and made a connection. Soon, they had a Zoom round table with the Congresswoman and Detroit-area musicians regarding streaming and the #JusticeAtSpotify campaign.

Tlaib was supportive of UMAW’s work and partnered with them to draft a piece of legislation related to their concerns. In March 2024, UMAW announced the introduction of the Living Wage for Musicians Act—led and co-sponsored by Tlaib and U.S. Representative Jamaal Bowman of New York. The legislation would create a new streaming royalty, funded through an additional subscription fee and a 10 percent levy on non-subscription revenue. That money would allow for the vast majority of musicians who build wealth for platforms like Spotify and Apple Music to make a sustainable income in the digital age.

It could be years before the legislation is voted on and enacted, but it’s the first step in making streaming payouts more equitable—and proof that traditionally siloed musicians can come together to effect major change. “The [Living Wage for Musicians Act] is the first action-oriented thing I’ve seen that gives me a little hope,” Fouriezos says. “It would be a life-changing amount of money to so many people.”

You do have to pay rent, and it would be nice if more people could do that by making art and making beautiful things.

Change will require consumers to play a role, too. Which may mean paying more to listen to music they love. But Dupuis and Nestel-Patt believe that listeners would be willing to shell out more for music if they knew that money was going to the creators. “People want to support their artists,” Dupuis says. “They want to see their favorite artists be able to tour for many years to come. And they're not aware of how low these payouts are and how they're becoming even lower and even less equitable.”

Raising awareness of those issues won’t happen unless there’s a cultural pivot away from the idea that making music should be somewhat miserable, Nestel-Patt says. Artists of all kinds have had to learn to romanticize the concept of suffering for their art—it’s a coping mechanism that every person in a creative industry has to let go of before they can demand more for themselves. But change will require artists to get brutally honest about the realities of trying to make a living off streaming and touring in order to build more public support for UMAW’s efforts, he adds.

Not that it’s easy. When artists do open up about how rough it can be, people jump on them—fellow musicians included—for not eagerly embracing a life of constant ramen. “Last year, the band Wednesday posted the economics of a tour to SXSW, and people were criticizing them for getting an Airbnb instead of sleeping in their van,” Nestel-Patt says. “This idea that you have to struggle for your art is ridiculous. If you're a salesman at a Xerox company, and you go on a business trip, no one's gonna be like, ‘sleep in your car.’ There's no expectation to hustle and struggle and live through hell for your work.”

Bringing artists together to have these types of conversations is important to UMAW. "Since musicians don’t have a central workplace, they see themselves as individuals, and usually only consider their own path and struggles and don’t see how all of these things play into larger patterns,” Dupuis says. The same reason someone might perform while they’re sick and not realize how that could put others at risk is the same reason they might accept unfair pay or gatekeep information about how much they’re making, she argues. Artists don’t always see how their personal problems connect to larger public, systemic issues. But for UMAW to keep moving forward, musicians need to recognize that they aren't operating alone.

The shifting of mindsets—of consumers and artists and big businesses—is not easy work. True transformation will require time. But who better to imagine a new way forward than a bunch of creators?