Say hello to Heracles inexpectatus, a parrot the size of a human child. But don’t worry, you won’t meet one face to face. Our new discovery, published today, lived around 20 million years ago in what is now New Zealand – adding to the islands’ rich and storied collection of remarkable bird species.

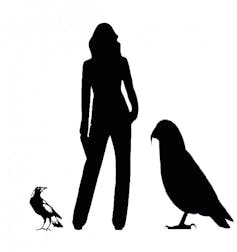

Heracles was truly a giant among birds. It was about 1m long, stood 80-90cm tall, and weighed about 7kg. That makes it about the same size as a dodo, and far bigger than its modern-day cousin, the kākāpō. Unsurprisingly, given its heft, it was likely also flightless.

Read more: Tall turkeys and nuggety chickens: large 'megapode' birds once lived across Australia

Islands are renowned for huge birds, perhaps none more so than New Zealand. Its fame in this regard began in 1839, when the English scientist Richard Owen first revealed the giant moa to the scientific world. In the next few years, many species of moa were named; now there are nine species in six genera, making them the world’s largest grouping of flightless birds.

Another famous island giant was the dodo of Mauritius. The dodo, now extinct, was a giant pigeon, rivalled in size only by Natunaornis altirostris from Fiji.

Other now-extinct giant island birds represented outsized versions of various familiar bird types. There were giant flightless ducks (Moa nalos) in Hawaii, a giant flightless swan on Malta, and two prehistoric giant geese from New Zealand. Giant predatory hawks and owls roved about the Caribbean islands, preying on the giant rodents that also lived there.

Although islands, with their isolation and lack of interbreeding, are perfect breeding grounds for outsized creatures, there is no pattern to predict which bird family might spawn a giant on any particular island.

New Zealand’s birds have long been considered unique in that it was they, rather than mammals, who dominated the land. They included an unusually high number of flightless species, often very large, and most found nowhere else besides New Zealand.

This is epitomised by the kākāpō. It is the heaviest living parrot, potentially weighing more than 3.5kg, and the only flightless one. It is nocturnal, and now critically endangered, the last surviving member of its family, Strigopidae.

Kākāpō, as well as the cheeky alpine kea and kākā represent a group that separated from all other parrots relatively early during their evolution. Cockatoos were the next to branch off. These facts suggest that parrots evolved in the region that is now Australia and New Zealand. But their exact evolutionary history remains elusive.

Branching out

Now our research team at Flinders University, the University of New South Wales and Canterbury Museum has shed some light on these issues. Our new research, published in the journal Biology Letters, reveals a newly discovered prehistoric giant from New Zealand - the first known giant parrot.

We discovered Heracles in the St Bathans Fauna, a collection of 20 million-year-old fossils from Central Otago.

Over the past 20 years, our research has discovered around 40 species from the St Bathans Fauna, including a wealth of fascinating prehistoric bird remains. These include eggshell and fragments of moa ancestors, a tiny kiwi, many ducks, a couple of pigeons, flightless rails, hawks and eagles, shorebirds, songbirds, and several small parrot species. Crocodilians, turtles, bats and even rare land mammals complete this eclectic group.

Heracles now reveals that another avian giant existed in this fauna. For the first and only time since, a giant parrot occupied the herbivore/omnivore niche on a forest floor.

Delayed discovery

Remarkably, the fragments of bone that allowed us to discover this giant parrot had sat on a shelf since 2008, patiently waiting for their turn to be described. We had known that St Bathans also contains eagle fossils of similar size, so the Heracles fossils were put on the eagle pile while we waited to find some more fossils that might tell us more.

But upon pulling them out and looking more closely, it was immediately clear that these were not eagle bones, so we started trying to work out what they were. Parrots were not on our radar at first, purely because these bones were far larger than those of any known parrot. But after a while the bones told their story – they were of a parrot, and nothing else was remotely similar. Moreover, they were in some ways fairly similar to the kākāpō.

And so Heracles inexpectatus was born, the name derived from Greek mythology. The large New Zealand parrots, kea and kākā, are in the genus Nestor. The mythical ancient Greek hero Heracles, in Latin known as Hercules, killed Neleus and his sons, except for Nestor. So it is only fitting that this giant parrot, an ancient predecessor of Nestor, be bestowed the name Heracles. Neleus, Nestor’s father, we had already used for the genus of small parrots Nelepsittacus that lived with Heracles. The species name inexpectatus relates to the wholly unexpected nature of discovering a giant parrot.

Read more: A case of mistaken identity for Australia's extinct big bird

So what was a giant parrot doing in ancient New Zealand? What did it eat? Could it have had a taste for meat, as the kea still does? These mountain parrots prey on the chicks of burrowing petrels and are notorious for attacking sheep.

But in New Zealand 20 million years ago there were no sheep, and in fact no large mammals at all. Probably, like most parrots, Heracles ate plants. Its size meant no fruit was too big, no nut too tough to crack. And the botanical evidence shows that it lived in a rich and diverse subtropical forest, where cycads, palms, casuarinas and up to 60 species of laurels thrived.

All these plants would have provided a rich bounty for this large parrot. But we warrant that it likely still snacked on moa occasionally, as kea still did more recently, when they got mired in swamps.

This article was coauthored by Professor Paul Scofield, Senior Curator of Natural History, Canterbury Museum.

Trevor H. Worthy receives funding from Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.