A Walmart cashier, a lemonade vendor, an aspiring fashion designer and a graduate with a degree in native plants. These are some of the eclectic back stories of the first-ever, all-female wildland firefighting crew of the California Conservation Corps (CCC).

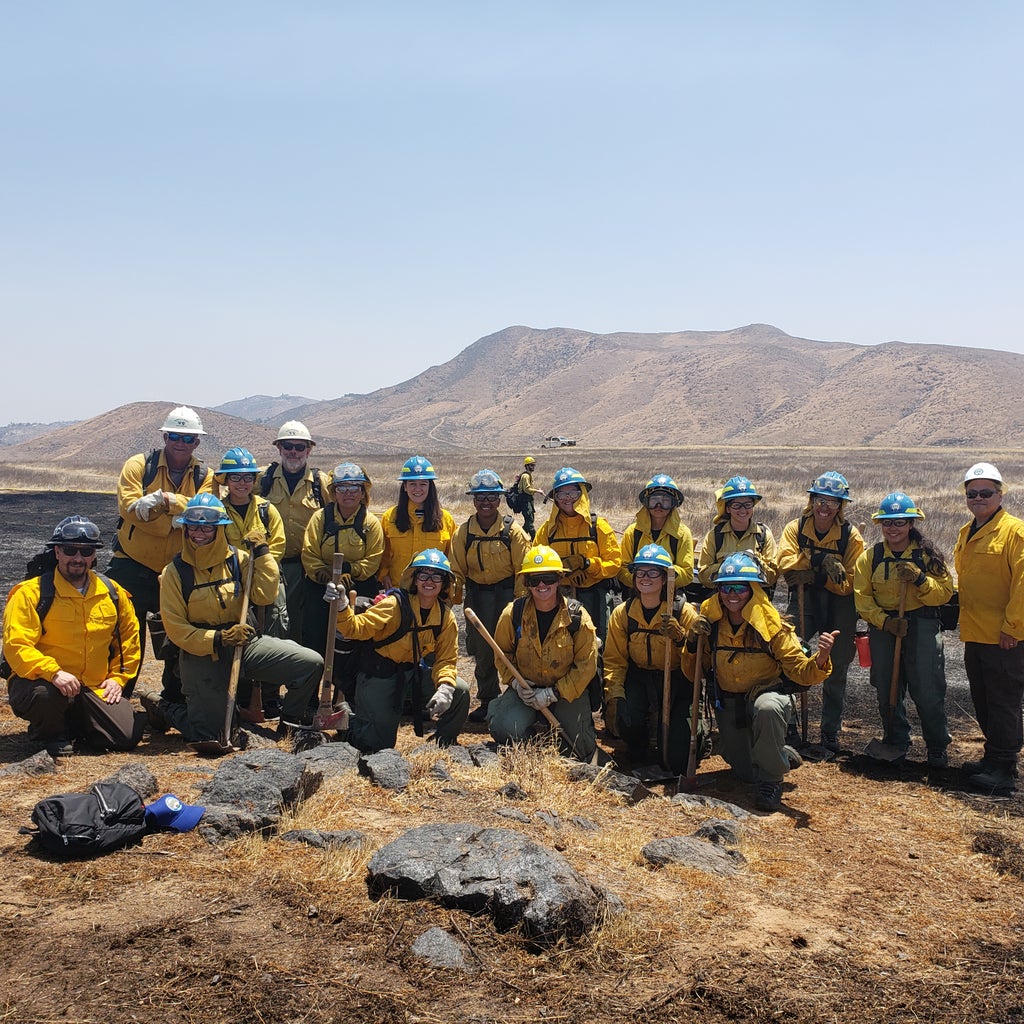

Inland Crew 5 from San Bernardino are a cheerful, wise-cracking and gritty band of 14 young women who have stepped up to the daunting challenge of fighting the state’s worsening wildfires.

The crew is part of the CCC, or “Cee’s” as it’s often dubbed, America’s oldest and largest conservation corps. Since the mid-Seventies, those aged 18 to 25 (or up to 29 for military vets) have joined its ranks as “corpsmembers”, where they train in an array of skills related to environmental work, fire protection, land maintenance, and emergency disaster response.

Inland Crew 5 is one of more than 20 fire crews acting as an informal pipeline for state and federal fire agencies who are trying to bolster numbers in the wake of longer and more extreme wildfire seasons.

Unprecedented blazes ripped through 4.2 million acres and 10,000 buildings in California last year, leaving 33 people dead including four firefighters. The National Weather Service issued what’s believed to be first ever warning for a “fire tornado” – a phenomenon caused by intense flames pushing hot air upwards – for an area near Loyalton, northeastern California.

Recommended

This year looks set to see another prolonged fire season. So far this year, 3,539 fires have been reported in California, compared with 2,875 over the same period in 2020. The number of acres burned has jumped 58 per cent year on year.

As more fires ignite and the demand for firefighters increases, the US National Interagency Fire Centre last week raised the national preparedness to level four on its 1-5 scale. It’s the fourth time in the last 20 years that it has hit that level in June. Around 9,000 firefighters are already on the ground, battling blazes.

Jasmine Valencia, 23, had jobs in boat sales and selling lemonade at music festivals before she saw a flier for the CCC while on a hike in Yosemite National Park. She joined Inland Crew 5 in December and has already been on the ground fighting fires.

“At first it feels like you’re on a different planet,” she tells The Independent. “It was eye-opening, like, ‘Oh, I’m really doing this.’”

While the climate crisis is the backdrop of larger, more frequent and erratic wildfires, on the ground it’s a complicated picture. California is in a race against the clock to cull dried-out vegetation that allows fire to spread quickly.

Inland Crew 5 is “type-II” – carrying out the gruelling, unglamorous backbone of firefighting work. “Type-I crews go directly to the fire for the initial attack and establish the fire line,” explains Rhody Soria, director of the CCC’s Inland Empire District. “Type-II crews fall in behind to do mop-up – clean-up on the fire line and putting out flare-ups in the area.”

14,000

The number of acres burned by wildfires so far this year, more than five times the area at this point in 2020

He adds: “However there are times because of wind or weather, when the fire blows up and they have to fight because they’re the closest crew.”

The work is not for the faint of heart. It’s 6am call times and long days of dirty, demanding work at times in triple-digit heat. On active fires, working for 24 hours straight is not uncommon.

It near-perfectly sums up the CCC’s inimitable slogan: “Hard Work, Low Pay, Miserable Conditions and more!” (Former California governor Jerry Brown, who conceived the programme, called it “a combination Jesuit seminary, Israeli kibbutz, and Marine Corps boot camp”.)

Fire crews use hand tools like the “Pulaski”, a combo of an axe and adze, or the “McLeod”, a hoe and rake in one, to dig trenches and hack out undergrowth to create perimeters for containing the fire. They are trained in power tools and chainsaws which come in handy for downed trees and take classes in first aid, CPR, safety protocols and weather patterns.

New recruits must pass a “pack test” to join the fire crew, completing a three-mile walk in 45 minutes while wearing a 45lb vest – like carrying a four-year-old child.

One day last month Inland Crew 5, who are partnered with the federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM), were monitoring prescribed burns on a grassy hillside near drought-ravaged Lake Matthews. Prescribed, or controlled, burns are deliberately set and tightly monitored by fire crews with the goal of reducing parched vegetation which can catch on the smallest spark.

Dressed in their distinctive uniform of flame-resistant Nomex green pants, yellow jackets and hard hats, Inland Crew 5 lined up along the wall of smoke and flames to ensure the fire didn’t spread.

The crew, who carry 40lb-plus packs, also ran hose drills. It’s an exhausting process even without a fire bearing down. They roll out yellow hose and attach additional lengths by clamping the gush of water, in order to follow the racing flames. When complete, rewinding the hose requires a laborious, figure-of-eight technique using both arms, which seasoned corps member Miracle Darnell demonstrated for new recruits.

Ms Darnell, 24, has been with Inland Crew 5 for the past two years and hopes to join a fire engine crew next season.

“I didn’t think [firefighting] was an option and didn’t know how to go about it,” she says. “I see that with hard work and connecting with the right people, that it is possible for me. I would have never known had I not come here.”

She adds: “It shows a totally different side of the [firefighting] field. It’s amazing to be able to work with these ladies.”

The concept of an all-female crew came together about three years ago, after the BLM approached the CCC because it was having a difficult time recruiting women firefighters.

US fire departments do not reflect the country’s make-up. The fire service is almost 96 per cent male and 80 per cent white. It is something fire chiefs have acknowledged. “[We] will provide a higher level of service to the communities we serve when the people of that department respect the culture, language and beliefs of the people within that community,” Ralph Terrazas, chief of the Los Angeles City Fire Department, has said.

The CCC approach has worked. “We’re into our third season,” Mr Soria says. “At least half the crew each season gets picked up by the [US] Forest Service and a good portion by the BLM. We even had some go to Cal Fire. It’s something we’re proud of.”

You have to sit down and think that you might not come back home and be OK with that

Corpsmembers get a monthly stipend of around $1,905 and health insurance, along with being able to earn scholarship money. They must also get their high school diploma if they haven’t already.

“They have to go to school for two hours each day. They come in from the field, have 15 minutes to wash up and go directly to the classroom, although studies moved online during Covid,” Mr Soria says. “It’s not an option.”

Mr Soria concedes that while corpsmembers might currently make more money working at a fast-food joint, it’s the career options that the CCC provides which keeps young people signing up. Clearly corpsmembers think so too: some commute for more than an hour and have been known to take two buses each morning to reach the Inland Empire Centre HQ.

Inland Crew 5 has also attracted recruits with a broad range of skills. Michelle Thompson, 24, studied native plant science at college, and came to the fire crew after a BLM internship.

“[The fire crew] was recommended to me because I love being out in nature,” she says. “This is a good way for people who want to be in conservancy or restoration to get their foot in the door.”

Restoring native plants and protecting California was also key for 22-year-old Paulina Gault when she joined last July. She had been studying fashion design at college before Covid moved her classes online.

Her parents were corpsmembers on fire crews in the early 2000s. (Mr Soria says this is a familiar pattern and he often meets the children and siblings of former members.) Ms Gault’s father subsequently joined the US military while her mother teaches classes on native plants, incidentally attended by fellow crew member Michelle.

Ms Gault hadn’t particularly considered the fire crew until she heard about the all-female team.

“I wanted to take a year out [from college] to see what happens,” she says, noting that she would likely go back to school to finish her degree and potentially be a seasonal firefighter.

Read more of the special reports from our Supporter Programme

She adds: “I feel a lot of people that join the ‘Cees’ are very conscious of the environment, luckily. I feel like we need to protect what we have.”

Yezenia “Yezzie” Ruiz, 22, joined the fire crew in December 2020 after Covid also upended her college studies.

“I wanted to find a good job to fill that gap year and found the CCC online,” she says. “I decided to give it a try.”

Ms Ruiz has already experienced being on the front lines of a fire. “They weren’t major fires but it’s a preview to what fire season is going to be,” she says.

Although she is comforted by the fact the crew is well-trained, she has contemplated the gravity of what lies ahead.

“It is exciting but it’s a serious job,” she says. “You have to sit down and think that you might not come back home and be OK with that.

“I think everyone on the crew has thought about it.”

Inland Crew 5 could be posted to active fires anywhere in California. “While [fighting] one fire, sometimes another fire pops up and they get bounced from location to location,” says Angel Lizaola, project manager at Inland Empire. “It takes a lot of dedication.”

At 28 years old, Chelsea Noler is the oldest member of Inland Crew 5 and leads the team as a “Conservationist 1”. She describes last year’s fires as “non-stop” when back-to-back, 16 hour-days for several weeks at a time became a familiar routine.

“It not only takes a lot of physical strength but mental strength” she says. “The focus is on keeping each other safe, and when you’re away from home, missing your family, we try to keep each other going.”

She adds: “But what’s amazing when you’re fighting these fires is that people come up and they thank you for what you’re doing.”