In the 1950s, the Soviet grandmaster Alexander Kotov wrote the book Think like a Grandmaster, which became an instant classic. In the 90s, growing up as a chess-crazed boy in pre-Internet India, this book assumed a mythic aura within our circle. It seemed to hold the secrets of supremacy in this maddening, intoxicating game. Kotov took on the mantle of a Drona, whose astras were almost impossible to attain, but once mastered, gave supreme power to the wielder’s hands.

ALSO READ: India’s love affair with chess

After carefully monitoring the movement of nears and dears to ‘abroad’, I was able to lay my hands on it thanks to an uncle settled in London. The opening pages seemed simple enough (the first step to evaluate a position was to count how many pawns you had and compare that number to the opponent’s), but with bewildering rapidness, Kotov introduced the ‘tree of analysis’, complete with diagrams and graphs. The trunk of this tree was the move you were considering, its branches were all the possible replies of the opponent, your possible response to their response were the sub-branches and so on.

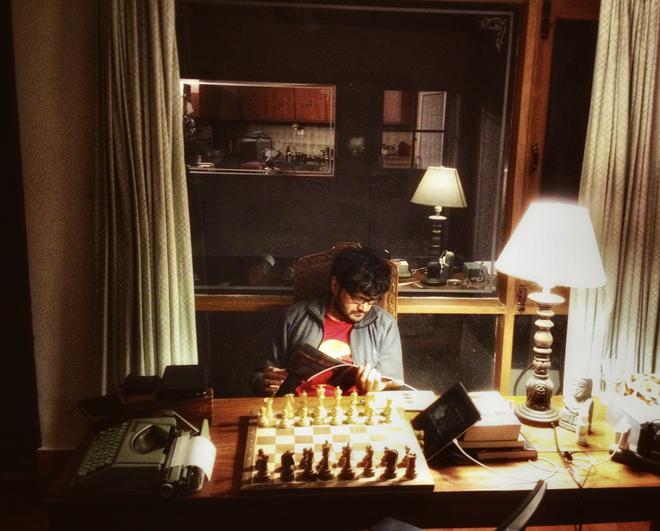

Immediately, the world plunged into an eternal forest, where tigers prowled, a forest I have not yet left, and perhaps will never find my way out of. Many years later, my grandmaster ambitions long gone, I was working with the filmmaker Amit Dutta on a script involving the royal game. I immediately transplanted this Kotovian forest to his neighbourhood, the thought-forests as immense as the stands of deodar and oak in the Himalayan foothills near his home studio in the Kangra valley.

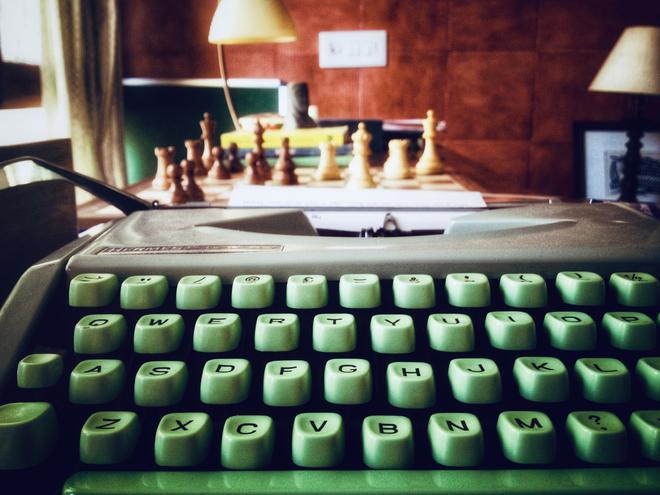

I wrote every morning to the hammer of typewriters (Dutta also collects decrepit typewriters and coaxes them back to health). His latest patient is a portable Hermes; the mint green of its keys are so alluring that I’m tempted to type something, anything, just for the haptic inspiration.

Our conceit was that unlike Kurukshetra, the trouble between cousins is resolved through a giant chess tournament in a purpose-built city. The games drag on for years, decades even. And the inhabitants of the city live their lives, grow old, wait, pondering over each move relayed from the games hall.

Yet there is a thread that connects from our imagined city to the Olympiad in Chennai.

Chess on the rooftop

Dutta has been described as ‘the most famous Indian filmmaker you may have never heard of’, whose works have been feted at film festivals and by critics . Dutta laughs, “I mainly play chess and steal time from it to make films and write books.” He tells me, “that I discovered chess, is a miracle to me. I grew up in a small village 30 km away from Jammu city. My close friends were three Sikh brothers, two of whom were amazing chess players. They taught me the Indian rules, where the pawn moves only one square and the king castles by jumping like a knight and then comes back — a fascinating and peculiar movement. The three of us became obsessed with the game and played it all the time.”

It was then that Dutta first sensed the addictive quality of the game and how it affected everyone around. “Our parents got so upset that they started throwing out our only wooden chess board; soon the knight lost its neck, the king its crown, and some pawns were lost altogether and replaced by whatever was in hand: eraser, coin or pencil stub.”

He describes an idyllic childhood, afternoons spent playing chess on the rooftop, drinking Rooh Afza, and eating Kashmiri apples. Later, growing up, he taught himself notation from a Soviet book, began to study games from the past, and shifted to modern chess rules. This way, he was retracing an earlier mental caravan route. There is a whole class of openings in chess collectively called the ‘Indian defences’. This involves moving the pawn one step forward to give space to the bishop. The name is a hat-tip to Mahesh Chandra Bannerjee, who in the 1850s became known to history through his games against John Cochrane, one of the leading players at the time. Such a pawn move is reminiscent of someone transitioning from Indian rules to modern rules, and Dutta and his friends also unconsciously recapitulated phylogeny.

Human limitations

Dutta’s interest continued through college, where films took over; he then got admission to the Film and Television Institute of India, where he developed another life-long habit, an even worse addiction, of collecting rare Indian chess books. He says, “I find it quite inadequate when the game is just mentioned as a war game. Especially when studying texts like Vakroktijivita, Dhvanyaloka, and Kavyaprakash, which expound very advanced systems of thought surrounding aesthetics, linguistics, and semiotics, I can sense an abstract congruence with a game like chess.”

Dutta explains, “In chess, the most elevating moments, harmonious or dazzling arrangements, are reached through a ladder of pattern-mapping, and given the inexhaustible possibilities of the moves, the ways in which the game can surprise and reward us are theoretically endless. It is only human limitations that can be exhausting.”

We often meet online to play. This evening I got a WhatsApp message, ‘a best of 4 match?’ I agree and log in around 11 p.m. During such a game some years ago, while we were chatting, I’d sent an article by the philosopher Steven Gerrard. This would eventually lead him to make a film, Wittgenstein Plays Chess with Marcel Duchamp, or How Not to Do Philosophy, which won multiple awards.

“Let’s play some bullet,” he says. Bullet is the term for ultra-blitz, where you have one minute to think for the entire game, distilling it to pure intuition, or pure fingerfehler, depending on how you look at it. Dutta consistently opts for the Caro-Kann defence, which bristles like a porcupine. He almost delivers checkmate with his bishops crashing into the pawn fortress around my king, but I escape in the dying seconds.

I look at the clock, it is almost one in the morning. The best of four turns into a best of 16 and then we keep playing, the game colonising our time, turning into a maze that snares thought. He jokes, “if you play chess it’s the sign of a gentleman, but if you play chess well it’s the sign of a wasted life.”

The author is a freelance writer and graphic novelist.