I am at Lightroom Bookstore, a much-loved independent children’s bookstore on a quiet street in Bengaluru. I ask for two recently published books, and I’m told with a mixture of glee and regret that they are both sold out.

Now, I didn’t ask for the latest book by David Walliams or Julia Donaldson. I wanted picture books by illustrators Priya Kuriyan and Rajiv Eipe, both published by Pratham Books. Eipe’s is a wordless one about a street dog run over by a car who is nursed back to health by a good Samaritan. Kuriyan’s book is about a rookie cop in Kerala on her first case. Finding a missing buffalo. Called Beauty.

Seeing the story in context

In India, where the children’s book market is dominated by global bestselling authors, countless mythological retellings, and anthologies of the homespun wisdom variety, the popularity of these two Bengaluru-based illustrators seems like an anomaly. Say their names, and parents, librarians and children will beam with pleasure, and rattle off their favourite books by them.

Ever since I became a parent, their books have graced the bookshelves in our home. The first set of picture books we purchased included Dinosaur-As-Long-As-127-Kids by Geetha Dharmarajan and illustrated by Eipe (Katha Books) and I’m So Sleepy written by Radhika Chadha and illustrated by Kuriyan (Tulika Books). Both were their first attempts at picture book illustration and since then, they have gone on to do many books that have delighted readers: at nearly 40, Eipe’s tally is close to 30 books, while 41-year-old Kuriyan has published almost double that.

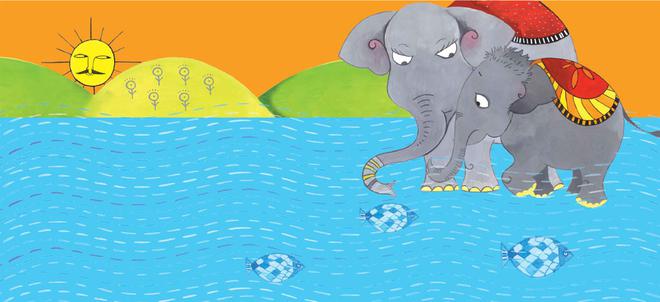

“When I illustrated I’m So Sleepy, I was trying to make an Indian-looking picture book,” admits Kuriyan, referring to the miniature style of painting that permeates the illustrations. “Over the years though, I have discovered a fondness for the familiar and the everyday, and I think more of the context of a story when I start a project.”

In more recent books, Kuriyan has used mixed media and collage, painstakingly cutting out bougainvillea leaves from pink paper, or painting over newspaper and fashioning them into everyday objects. In the picture book adaptation of Perumal Murugan’s Poonachi, the colour palette is red and black, hinting at the danger and death lurking in the forest. When I ask about how she narrows in on a style, she says, “I let the story guide the treatment. I don’t consciously ‘push the envelope’. Instead, I think of how to set the story in a context that seems real, relatable, contemporary and observant of socio-political life around us.”

It’s this ability to look at the mundane with keen eyes, and depict them with a certain fondness and wit that make both their works so memorable. Women wear sneakers with salwars, children have unibrows, and grandmothers have chin hair.

Digging into their childhoods

In Eipe’s book Anand, about a municipal waste collector, the look on a woman’s face as Anand comes to take away her garbage is rendered perfectly. She wants the unsightly mess and the smells her family have accrued gone, along with the man who collects it. Anand’s expression shows that he understands, but also that he can’t be blamed.

This skill has no doubt come from decades of drawing, going back to school years. Eipe spent the first decade of his life in Chennai, before moving with his family to Mumbai where he attended the J.J. School of Art to study fine art. “Caricaturing teachers was a pastime in school, and when I was caught, rather than telling me off, my mother bought me paints, oil pastels, sketch books, canvases and easels,” Eipe tells me over a Zoom call. It’s something parents and educators might want to take note of: that we must find ways to quietly support our children’s creativity, and not squash them or shape them into something we find acceptable and ‘useful’.

Kuriyan’s family moved around frequently when she was in school. She says, “Schools, teachers, neighbours and friends were not constants in my life. So my sketch book became my constant.” She remembers being ‘like wallpaper’ in school, and not wanting attention from anyone. “I just wanted the school day to end so that I could go home, and sketch.”

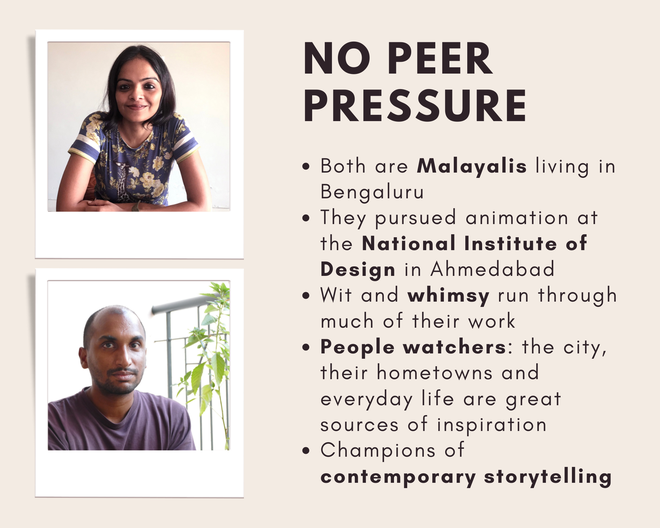

These childhoods spent observing and drawing led them both to pursue animation at the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad. Luckily for us, they stumbled into illustrating books for children quite by chance. Making books for children is certainly not lucrative in India, especially when compared to commercial animation. So it begs the question, why make them?

“Drawing is the one thing I can do to be useful in the world. It’s extremely joyful to be a part of book-making, and know that you are aiding the process of enriching someone’s childhood. When you make a book, it exists in the world forever, if not in print, then in the minds and memories of readers,” shares Eipe, who till recently ran his own animation studio. Kuriyan feels that her motivation is sometimes selfish. “I get a big high from creating scenarios, observing people and their lives, and making a story out of it. And it feels like I’m making a difference in some way.”

Peopled by the familiar

And their work does make a difference, not just by entertaining young readers, but also by subtly challenging prevailing norms and attitudes. In Kuriyan’s Ammachi’s Glasses (Tulika Books), readers get a slightly different grandmother, feisty and adventurous, a refreshing diversion from the typical cuddly and sanitised portrayal.

In Eipe’s collaboration with writer C.G. Salamander in Maithili and the Minotaur (Puffin), a young witch lives at the edge of a human town while attending school in the magical wilderness. She’s an outcast in both places though she tries hard to fit in. The first in a series of fantasy graphic novels, it’s a dark and beautiful story about friendship and our need to belong.

Though the two have never collaborated, there are a number of parallels one can draw between their work. Both are Malayalis who have lived outside the State, love drawing ammachis and are keen people-watchers: Eipe sometimes from the table at a local Darshini (a restaurant chain) in Bengaluru, while Kuriyan shares that some of the characters in Beauty is Missing were spotted when strolling down the street of her hometown in Kochi during the COVID lockdown.

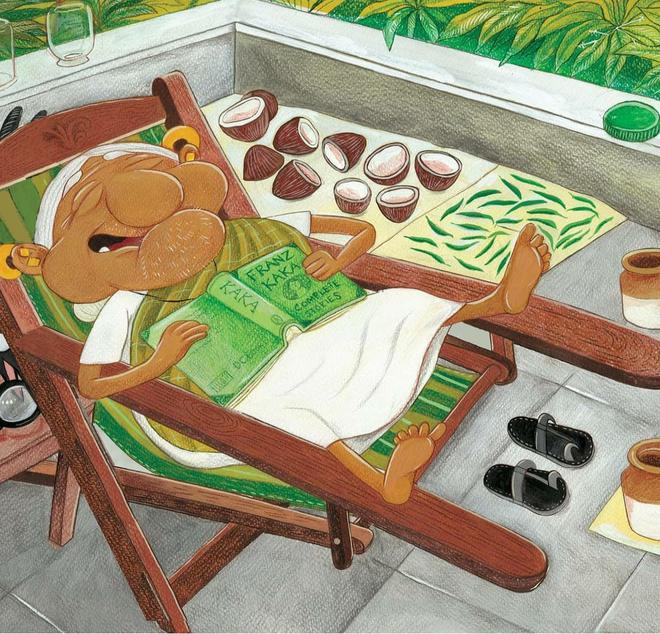

Another similarity is that their illustrations are peppered with inside jokes. Like the delightful animated films for children which have something for the adults watching as well, Eipe and Kuriyan always offer something for the grown ups, too. One of my favourite spreads in Ammachi’s Glasses shows the grandmother fast asleep with The Complete Works of Franz Kaka on her chest while a crow steals her glasses.

Contemporary storytelling and some whimsy

While readers clamour for new books from them, as artists, what do they hope for in the coming years? Kuriyan would love to see more experimentation with the form of the book itself. “We see very little in terms of pop-ups and fold-outs at the moment, where the form is really part of the story itself.” Eipe hopes for more contemporary storytelling in Indian languages from a more diverse pool of creators, as well as books that attempt to tackle complex themes and contemporary concerns. And of course, stories that celebrate whimsy and silliness.

In the 13 years that I have been buying books by Eipe and Kuriyan, it’s been a privilege to see their work evolve, but also in some ways, stay reassuringly familiar. While their art has always been unabashedly Indian, I find that the way they both interpret what that means has become more nuanced. My children may now be well out of the picture book phase, but I still buy their books, usually for myself. Sometimes, my now 14-year-old will see something by one of them and say, “Oh! I know this! You used to read me their books when I was small.” He’ll set aside the manga he is reading and settle down with their picture book, cocooned by the worlds they so beautifully create.

The first in a series on children’s books illustrators from across the country.

The writer is a children’s book author (Loki Takes Guard) and columnist based in Bengaluru.