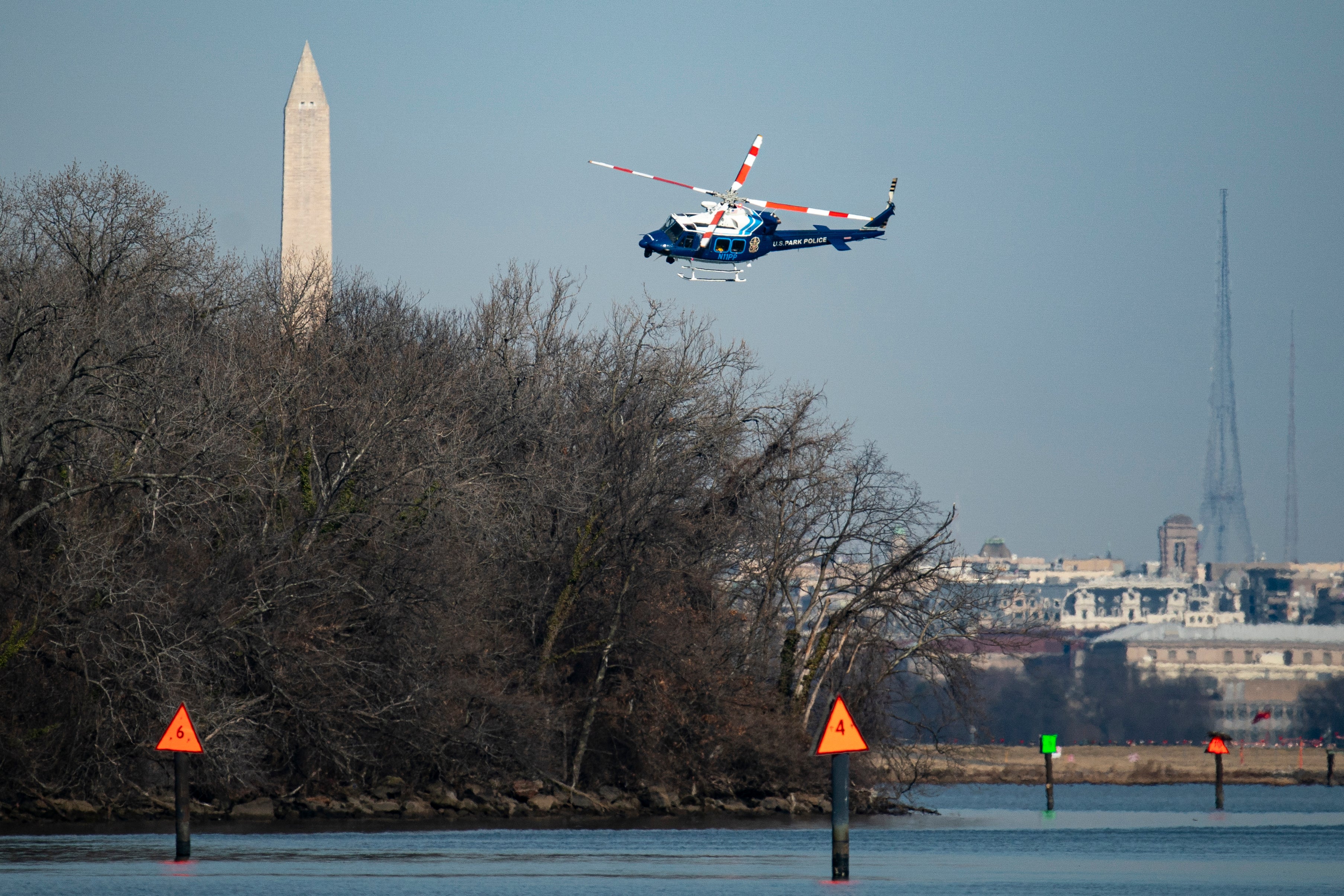

The fatal midair collision on Wednesday evening between an Army UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter and an American Airlines passenger jet moments away from landing at Washington, D.C.’s Reagan National Airport was a shocking and extremely rare occurrence, according to experts who believes human error is the likeliest explanation behind the tragedy that claimed dozens of lives.

In audio of the tower at Reagan communicating with the helicopter crew, a controller can be heard asking if they have the airplane in visual range, telling the chopper to pass behind the jet. Moments later, the two smacked into one another, killing all 64 people on the plane, which was flying in from Wichita, Kansas, and the three service members aboard the Black Hawk. On Thursday, officials with the National Transportation Safety Board told reporters they were not yet certain of the tragedy’s root cause.

Philip Greenspun, an MIT professor and former Delta pilot who flew the same Canadair Regional Jet involved, touched down at the same airport countless times. To his mind, the crash was most likely the result of human error stemming from a confluence of factors. Chief among the possibilities, he surmised, could have been a misunderstanding between air traffic controllers and the Black Hawk pilots. Further compounding factors may have included visual distractions, mistaken assumptions by controllers about the Black Hawk’s intentions, and idiosyncrasies inherent in the collision warning devices aboard both aircraft.

Greenspun — who is also an FAA-certificated helicopter instructor and has trained Black Hawk pilots to fly civilian choppers — has spent hundreds of hours piloting helos around Boston’s Logan Airport, and said it “would be very rare to need to cross the approach or departure corridor.”

“You usually do try to avoid it, if possible,” he told The Independent, while noting that helicopters in the D.C. area still “inevitably cross the paths of airliners,” and have for decades, without colliding. (Nevertheless, roughly two-thirds of the rare midair collisions that do occur, happen during final approach.)

Among the additional issues that could have contributed to Wednesday’s collision, Greenspun pointed to a potential misunderstanding between air traffic controllers and the Black Hawk pilots, who were instructed to keep sight of the American Airlines CRJ, one of several in the area at the time, and maintain visual separation.

However, Black Hawk pilots fly wearing helmets, and often, at night, using night vision goggles. Helmets significantly reduce peripheral vision, as do the goggles, which can also make it harder to see brightly-lit objects against dark backgrounds, like an airliner in a dark sky with its landing lights blazing. As the airliner was lined up on a glide path, ready to land, the helicopter should have had an easier time getting out of the way, but didn’t, according to Greenspun.

“I’m 99 percent sure the Black Hawk [crew] was confused about which airliner they were talking about,” Greenspun said.

On that note, he wondered why the control tower failed to warn the Black Hawk that it needed to immediately deviate from the course it was on, and give them a stronger warning than simply asking, about 20 seconds before impact, if it had the CRJ in sight. The Black Hawk crew answered that yes, it did, but there were multiple aircraft in the vicinity and Greenspun thinks they were likely referring to the wrong plane.

The controllers at such a busy airport “are about as good as you can get,” according to Greenspun, who said the pilots at the controls of an airliner are also top tier, and that Army Black Hawk pilots “are well above average.”

The situation on Wednesday was “totally routine,” and one that air traffic control, or ATC, was almost certainly “very comfortable with.”

“It’s a shame, because air traffic controllers really are excellent people, but, after 70-plus years of trials, maybe human excellence just isn’t enough,” Greenspun said, noting that those working in ATC towers are “working, basically, with 1950s technology.”

Likewise, Greenspan believes aircraft cockpits are in need of a major refresh, as well. A number of factors, among them the long development cycles involved in manufacturing commercial and military aircraft, mean the systems used typically lag behind even inexpensive consumer-grade ones available to the masses.

To that end, Matt Cox, who flew F/A-18 Hornet fighter jets for the U.S. Navy before transitioning into private industry, said his Volvo is “a lot more advanced, in terms of technology” than the $70 million airplane he piloted while serving in the military.

“The avionics in the Hornet were designed in the 80s and 90s,” Cox told The Independent. “The avionics package in a 757 cockpit was designed multiple decades ago.”

Still, the components that are presently in place have all but been perfected since the dawn of aviation 120 years ago, according to Cox, whose company, Beacon AI, is developing next-generation automated “co-pilot” software for both the commercial sector and the military.

At the beginning, Cox explained, mechanical error accounted for 80 percent to 90 percent of airplane crashes, whereas 80 percent to 90 percent of accidents today are caused by human error.

“Engines are more reliable, systems have multiple redundancies, as a society we’ve driven all of those causes down,” he said. “But, in those 120 years, the human brain didn’t have a similar renaissance.”

Human pilots are tasked with making the right decisions, as close as possible to 100 percent of the time, which means “hoping the helicopter crew finds the right plane [out the window] and does all the right things” to avoid hitting it, according to Cox.

But, he maintained, “Even the most skilled pilots are going to make human errors, because they’re human. We have wanted humans to be very much in control, and that has worked to get us to a great safety record today,” Cox said. “But it’s not going to keep us at the safety record we want.”

Full autonomy in the cockpit is still “a long ways away,” Cox went on, but, he said, “We do think there are some advancements that exist to bring to the cockpit alongside human pilots, driver-assist type stuff, to augment their capabilities and to help them to their jobs better. Does an automatic transmission make a bad driver into a good one? No. But it’ll make things a lot easier.”

Whatever happened specifically, Wednesday’s air disaster was “a bad f**k-up,” according to Mike Henderson, who owns a flight training academy in Livermore, California, and testifies as an expert witness regarding aviation accidents.

“If you were to try to hit an airplane with a helicopter, it’s pretty hard,” Henderson told The Independent. “The sky’s a big place. That said, collisions are more likely to happen where planes are the most dense.”

The American Airlines plane “was full-flaps, wheels down, in about 30 seconds, they’d be touching asphalt, and this chopper cuts in front of that,” Henderson said. “Somebody screwed up.”

It’s still far too early to assign blame for what happened, according to Greenspun, who said, “Most aviation accidents are [the result of] an accident chain,” he said. “You need more than one person to screw up… It really just shows you that humans are fallible.”

One thing is clear to him: DEI hiring is not to blame.

Greenspun pushed back firmly on President Donald Trump’s assertion on Thursday that diversity, equity, and inclusivity programs related to the hiring of air traffic controllers had something to do with the deadly crash.

“I don’t think DEI is a factor here,” Greenspun said, emphasizing that the incident occurred in Class B airspace, the busiest and most restrictive in the nation. “There are 37 Bravo-class airports in the US, and it’s largely merit-based… So yeah, I really don’t think that could be a factor.”