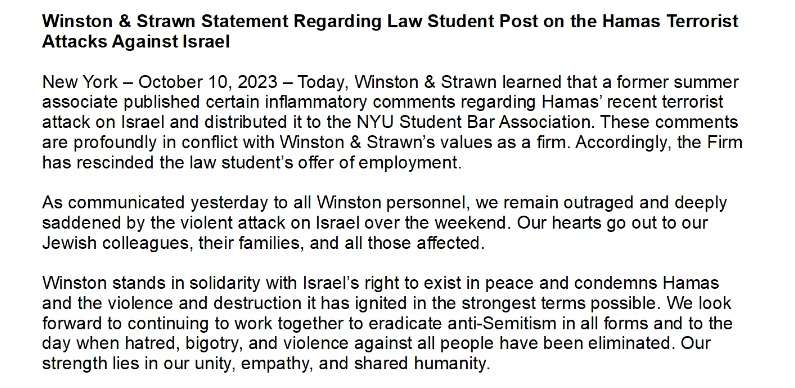

In recent days, we've seen some employers saying they'd refuse to hire people based on those people's praise of the Hamas attack on Israel (or at least certain kinds of praise), see, e.g., this story about one employer [UPDATE: and others] and this statement from another:

(For more on the particular statement that led to the revocation of the offer, see here.) Likewise, one can imagine other employers refusing to hire people based on those people's hypothetical praise of various kinds of Israeli retaliation against the attack. Is that legal, at least for private employers?

The answer is that it generally depends on state law, and sometimes even on county or city ordinances.

There is no general constitutional right of employers to refuse to hire people whose statements or actions are "profoundly in conflict with [the employer's] values as a firm." Federal and state laws, for instance, generally forbid discrimination in employment based on the employee's religion, however much the religion might profoundly conflict with the employer's values.

Such laws also ban discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, generally regardless of the firm's values. (There's a debate about the extent to which state or federal religious exemption rules provide an exemption from employment discrimination bans to employers who have religious objections to employing certain people. But, even if such exemptions are sometimes granted—and they mostly haven't been—that would be a special feature of the religious exemption regimes, and likely not available to employers who simply object on secular moral or pragmatic grounds.)

Federal law bans discrimination based on union membership, even if the employer is strongly anti-union and views union membership as contrary to its values. To my knowledge, all or nearly all states also forbid firing an employee based on how a person voted in various elections, however much that vote profoundly conflicts with the employer's values. Indeed, some states make such discrimination based on how a person voted a felony.

Likewise, a considerable number of states and some counties, cities, and territories ban discrimination based on various kinds of political activity, or speech more broadly (though a considerable number don't). The California statutes protecting private employees from retaliation for their "political activity," for instance, have been read as banning discrimination in firing or hiring based on an employee's "espousal of a candidate or a cause," including broad ideological causes and not just ballot measures.

Other laws are narrower, or sometimes vaguer. New York law, for instance, bans employment discrimination based on off-duty "political activities," defined to mean "(i) running for public office, (ii) campaigning for a candidate for public office, or (iii) participating in fund-raising activities for the benefit of a candidate, political party or political advocacy group." That seems largely limited to election-related speech, which wouldn't include advocacy of Hamas's actions or of Israel's retaliation for those actions.

But New York law also bans employment discrimination based on off-duty, uncompensated "recreational activities," defined to mean "any lawful, leisure-time activity … which is generally engaged in for recreational purposes, including but not limited to sports, games, hobbies, exercise, reading and the viewing of television, movies and similar material." Would that extend to posting about current events on Facebook or Twitter? That's not clear; compare Cavanaugh v. Doherty (N.Y. App. Div. 1998) (treating the law as covering "a discussion during recreational activities outside of the workplace in which her political affiliations became an issue") and El-Amine v. Avon Prods., Inc. (N.Y. App. Div. 2002) (apparently treating the law as covering plaintiff's "involvement in a vigil for Matthew Shepard, the gay college student who was brutally murdered in Laramie, Wyoming," Jennifer Gonnerman, Avon Firing, Village Voice, Mar. 2, 1999) with Kolb v. Camilleri (W.D.N.Y. 2008) ("Plaintiff did not engage in picketing for his leisure, but as a form of protest. While the Court has found such protest worthy of constitutional protection, it should not engender simultaneous protection as a recreational activity akin to 'sports, games, hobbies, exercise, reading and the viewing of television, movies and similar material.'").

Now what if the employer argues that the employee's or prospective employee's speech is so offensive to clients or coworkers that it undermines the employer's business? The laws also appear to vary as to that. Recall that, for instance, an employer can't raise such objections as a defense to firing employees based on their religious values; however much your customers may disapprove of Satanists or evangelical Christians or Orthodox Jews or Sunni Muslims, you can't use that as a basis for rejecting the employee.

Some of the state laws appear to be comparably categorical, though others have some exceptions of varying breadth. New York law, for instance, excludes situations where the employee's political or recreational activity "creates a material conflict of interest related to the employer's trade secrets, proprietary information or other proprietary or business interest." I doubt that this extends just to public hostility (however morally justified) to the speech (though see this federal district court decision); I think "other proprietary or business interest" refers to interest such as those involved with trade secrets or proprietary information, perhaps as well as other things that fit within the general understanding of "material conflict of interest." But the exact scope of this exception is not, to my knowledge, well-settled.

To be sure, in some situations an employer may have a First Amendment right to discriminate among employees, especially ones who speak on behalf of the employer. Churches have a First Amendment right to choose their clergy, notwithstanding bans on discrimination based on race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, disability, and so on. (They also generally enjoy statutory exemptions from the ban on religious discrimination as to all their employees, even low-level ones.) A newspaper may have a First Amendment to forbid political activity by its reporters (see pp. 280-83 of this article). But these are narrow exceptions from the general rules set forth by the state statutes I describe above, applicable to relatively narrow categories of employees.

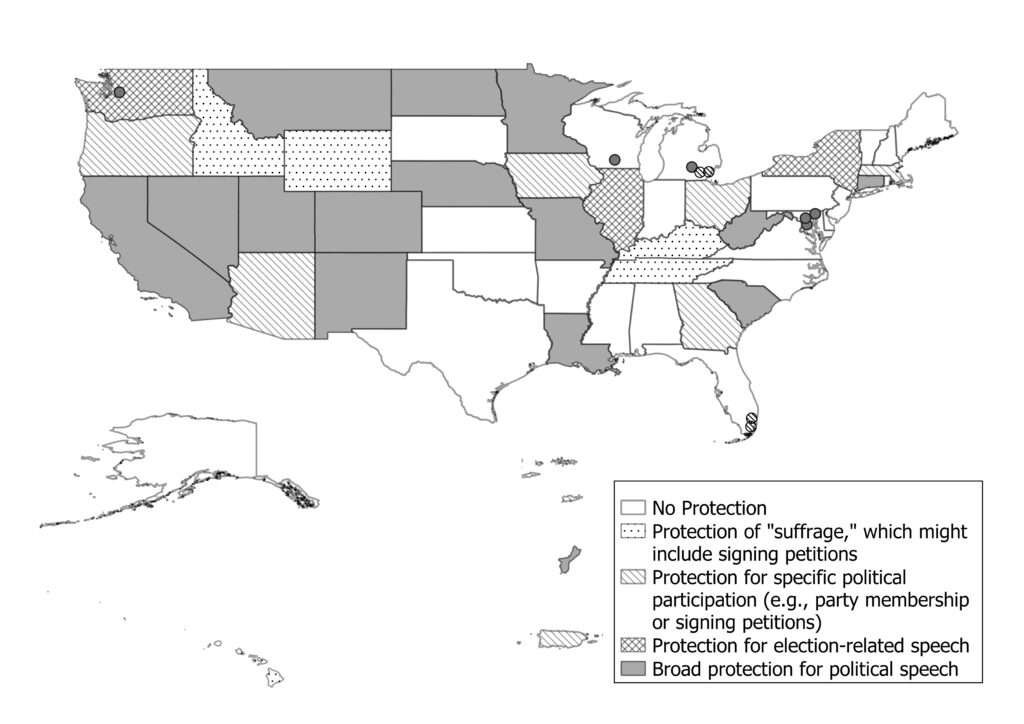

Here's a rough map of how the laws vary throughout the country, though you can see more details here.

Again, not all jurisdictions have such laws. But some do, and those may well provide legal protection for employees' political speech, including speech that many view as highly offensive. (I should note that I'm not opining here on the specific Winston & Strawn incident cited at the start of the post; again, that depends on where the student was going to work, and, if that jurisdiction has such a law, what its scope ends up being.)

Finally, for a more extended discussion of the policy arguments for and against such laws here.

The post May Private Employers Fire (or Refuse to Hire) Employees Because of Their Praise of Hamas (or Praise of Israel)? appeared first on Reason.com.