Max Porter walks into the Southbank Centre’s cafe and politely apologises for running late. Above the polyphonic din of a baby crying and music blaring, the author tells me it’s all the fault of his “close personal friend” Ruth Wilson. He’s got his tongue firmly in his cheek, but frankly, as excuses go, it’s a pretty chic one. The pair are in the throes of rehearsals, alongside actors Toby Jones and David Alade, for a dramatic reading of Porter’s latest novel, Shy, to be staged at the Southbank. It’s an unorthodox alternative to a traditional book launch: “The idea that I go out and be like, ‘I’m going to read a bit, now buy it’ is just not good enough,” he jokes. “I’m not saying everyone needs dramatic abridgements with Toby Jones starring, but what’s the point of this now we’re in a totally content-driven environment?”

Porter hasn’t been able to eat all morning, so he tucks into a cheese and ham baguette and a ginger shot as we talk. The author refers often to being a father, but with his slouched posture and youthful face it’s more like speaking to a wise, older brother. Shy is his fourth book, following his acclaimed debut Grief Is the Thing with Feathers, a Ted Hughes-inspired exploration of grief, and Lanny, a curious folktale about small-town England. His novels have scooped up a host of literary awards, including the Dylan Thomas Prize, and marked him as a phenomenal new talent. As a writer, he has a voice that is inimitable, a mesmerising blend of poetry and prose that dabbles with form; entire pages can be taken up by one line, words move in unexpected directions. Prior to his novels, he wore all possible publishing industry caps: he’s a former Daunt bookseller, and until 2019 he was the editorial director of Granta Books. The slender, strange Shy is characteristic of Porter: dark, furious, evocative and, above all, achingly tender. Taking place across a few decisive hours in the life of a troubled, angry young lad named Shy, who flees a school for kids with behavioural issues, it is perhaps Porter’s greatest exercise in empathy yet.

Shy is the third of Porter’s novels to place a young man at its heart; he describes it as the “climax of [my] books about boyhood”. He speaks honestly about his writing process, revealing the not-so-dormant editor in him and how he’s evolved from the heartfelt lyricism of his first novel, Grief Is the Thing with Feathers. “I feel like I’ve got more surgical with my fragmentary approach,” he says. “I deploy things very deliberately now, whereas I used to be more musical; I’d try that there, and see if it hums. Now I’m like, I know this will hum if I put that there, so that was quite satisfying.”

Porter set the book in the mid-Nineties as a way of stripping Shy’s story down to its barest parts and getting to the root of his emotional turmoil. “I think if you write about the present, it becomes harder and harder to keep the novelistic impulse out,” he says. “I don’t have a sophisticated understanding [of contemporary teen life] beyond a great unease about what mobile phones are doing to kids. I know it’s probably not good, but I would need to write about that and I’m not ready.”

The result is, as Porter explains, a “historical novel that breaks all the rules of historical novel writing”. As an example, he cites having Shy list all his favourite DJs on the first page as “the absolute no-no of writing a historical novel”. Shy listens obsessively to drum’n’bass, a passion and a lifeline in a world that continually overrules him. “I wanted to feel what it was like to be genuinely proud of a home-grown cultural product,” Porter says of the music genre that dominated Nineties British youth culture. “And what that might mean as a spring in a person’s step when they can’t see anything else to be proud or excited about.”

Porter describes the formation of Shy as organic, as if Shy himself revealed his story to the author. “Shy is the book I’ve written fastest and edited slowest,” he says. “To make sure that the work that I’m doing is for Shy, not for myself, and not even for a notional reader.” He talks about his character as though he is real, with such affection that the conversation starts to resemble a parent-teacher evening. “I don’t know what he looks like,” adds Porter. “Although a kid walked past me the other day on the street, hood up, headphones on. He had a storm on his face. I was like, ‘Oh, come here, man.’”

Porter is aware of recent conversations around the changing status of the male novelist, a category that was once so dominant but must now cede ground to other voices. “In the Eighties you couldn’t move for books by middle-aged white men about shagging their secretaries, which was great for them but not good for other people,” he says. “If they now feel sorry for themselves because that time has passed, then boo-shucks. If they’re still writing interesting things, then those books will be found and chart anyway. It’s just luck.”

Literature is freedom; if you’re offended, stop reading

He says that his ideal publishing landscape would involve authors simply leaving their books around for people to find them and read them. “Publishing is always going to be a scam because it’s part of capitalism,” he continues. “There are winners and losers. What one has to do, I think, when one has a voice, is for God’s sake be careful, and don’t want to cause offence for offence’s sake.” On the subject of sensitivity readers, the current literary bogeyman, Porter is frank: “I want us to be more sensitive, but do I think we should be notionally anticipating what might offend someone in a book and warn them against it? No, no... literature is freedom; if you’re offended, stop reading.”

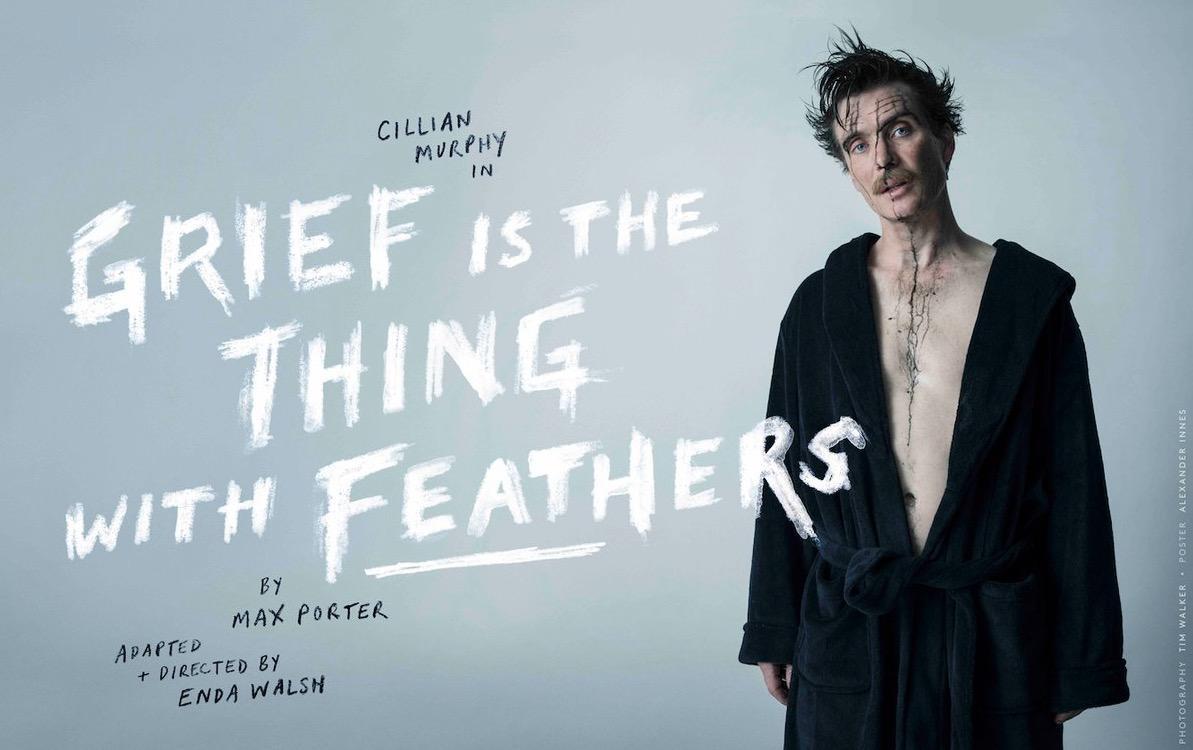

Perhaps it’s Porter’s deep well of empathy that has secured him a place as a prominent male voice in contemporary literary fiction. He tells me he became close friends with more men during lockdown, often going for walks with them. “I was never part of a gang of men,” he says. “But I would just walk around the park for an hour, and talk with a man friend.” In 2021, he wrote All of This Unreal Time, a short film monologue about personal regret and the bind of being a man, for Cillian Murphy, who had appeared in the 2019 stage version of Grief Is the Thing with Feathers. “That came out of conversations with Cillian about shame and awkwardness in the body and notions of apology,” he explains. “Shy came out of similar conversations with [Cillian] and other people, where I’m trying to embrace and unpack rather than hide from, deny or shrink-wrap the range of feelings one has about raising children, particularly boys.”

Though some may read Shy as a treatise on the emotional wellbeing of young men, Porter did not write it as such. “I didn’t find in any of those conversations with men that I should afford myself to sit back and novelise about it,” he says. “There’s no expert opinion, there’s no me writing the definitive book about teenage life. I didn’t do hours and hours of research about mental health in the Nineties, or these kind of [behavioural] schools, or the suicide epidemic among young men. That would have meant I had some role to reproduce that work in the book, when my role was to do what I do every day of my life and think as carefully as I can about a young person’s sense of self, and how I’m responsible for nurturing it in some ways, and in other ways utterly irrelevant to it.”

Porter recounts a pre-pandemic conversation with the writer and poet Ocean Vuong. “He was talking about this idea of people saying, ‘Oh, I’ll never read men again,’” he says. “Which is totally fine, anyone can read what they want, but if you chuck out, say, Philip Roth, that would be a mistake.” He acknowledges that “we’ve moved on from [Roth’s] gender politics”, but says that to dispose of Roth wholesale is “disempowering yourself as a reader.” “Empower yourself to think carefully about men and masculinity,” he says. “The binary of good and evil doesn’t exist, it’s there to control us.”

In 2017, two years after the publication of Grief Is the Thing with Feathers, excerpts from Sylvia Plath’s diaries alleged physical abuse. Given that Plath’s husband’s poetry fuels Porter’s debut novel, I ask whether Porter thinks similarly of Hughes as he does of Roth. “I was so upset by the revelations that I didn’t read any Ted Hughes for two years,” he says solemnly. “There are aspects of Ted Hughes’s oeuvre that I won’t revisit; there’s lots that I will, as he’s just an incredible poet. How to be both? We can have both.” He pauses for a moment, frowns. “If we don’t have both, we aren’t being human any more.”

‘Shy’ is out today, published by Faber