Masih Alinejad is under attack.

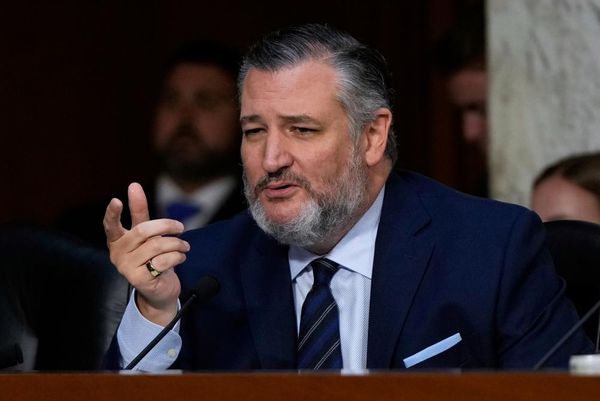

"The Iranian government is scared of me and I'm only 45 kilos," says Alinejad, an Iranian journalist and human rights activist who was banned from reporting in Iran and driven into exile 13 years ago.

She lives in New York, and after two known assassination attempts, she and her husband Kambiz Foroohar, a former reporter for Bloomberg, have been forced to go under FBI protection.

She's speaking to ABC News via Skype from a safe house. It's early October, just weeks after the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini sparked widespread protests across Iran and saw authorities unleash a brutal crackdown.

"Right now, Iranians are united and that scares the regime," Alinejad says.

"There's unity between the Iranian people and the Western people who care about democracy. This is a revolution against autocracy, against dictatorship, and it should be supported by anyone who cares about democracy."

It's messages like this that have put her and other outspoken members of the diaspora on a hit list.

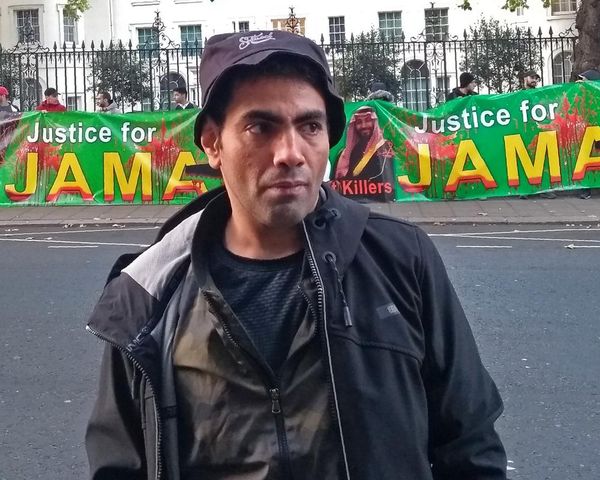

She says the Iranian government's latest attempt to hire operatives to kill her was in August this year when police apprehended a man acting suspiciously near her residence.

After arresting him, the police found a loaded AK-47-style rifle in his car.

She says in July 2021, the FBI arrested an Iranian national in California for plotting to kidnap her and take her to Venezuela, (a country which calls Iran's Islamic Republic as a great "friend and ally").

If the kidnapper had succeeded, she likely would have would been transferred to a jail in Iran.

Iran's Ministry of Foreign Affairs denied any involvement, calling the accusation "baseless and ridiculous".

Taking off the hijab

Even before Mahsa Amini's death saw Iranian women taking off their hijabs in the streets, demanding freedom, Alinejad has been convincing Iranian women to challenge the country's hijab law that requires girls, from the age of puberty, to cover their hair.

"This time, it's totally different. Because this is the first time after the revolution we've seen like women, shoulder to shoulder with men are burning the headscarves," she says.

"The headscarf is not just a small piece of cloth for Iranian women. It is the main pillar of a religious dictatorship. And for the Iranian regime, the headscarf hijab is like the Berlin Wall. If we tear this wall down, the Islamic Republic won't exist."

In 2014, Alinejad posted a picture on Facebook showing her in London with her hair flying in the wind.

Some women in Iran praised her image, saying how they were envious of her freedom — so she asked them to also share their unveiled pictures.

That was how her My Stealthy Freedom campaign began, and how Alinejad has built up millions of followers on her social media accounts.

Ladan Boroumand, co-founder of Abdorrahman Boroumand Center, a Washington-based organisation that advocates for human rights in Iran, says that Facebook post sparked "one of Iranian civil society's biggest challenges to the regime yet".

"She [Alinejad] and the women who posted selfies sans hijab on the page created an alternative public sphere that was immune to police assault," Boroumand wrote in September.

"The internet allowed these women to do what their mothers and sisters could not in 1979."

In response, the regime intensified its repression, punishing women who refused to veil in public with fines, lashes, and jail sentences.

The head of Tehran's Revolutionary Court in 2019 said those sharing protest videos with Alinejad (who Tehran considers to be acting on behalf of the United States) could be jailed for up to 10 years under laws relating to cooperation with an enemy state.

"The way that they [Iran's leaders] talk is murdering, killing, taking hostages, bringing family members of those people who got killed on TV and forcing them to say that our daughters, our teenagers, committed suicide," Alinejad says.

"This is the language that the Islamic Republic use not only with Iranians, but with all the Western citizens."

But that doesn't stop Alinejad, who is calling for world leaders to stand up to the regime, which she argues is "no different from ISIS or the Taliban", and which she often compares to the to the totalitarian society depicted in the TV series and novel, The Handmaid's Tale.

"The West must recognise the [current] Iranian revolution," Alinejad tells the ABC. "Otherwise, they have to deal with these Islamic terrorists on US soil, on Australian soil, in the western countries."

The 'outspoken feminist'

The self-described "outspoken feminist" has been on the Islamic Republic's radar for two decades.

She's currently a member of the Human Rights Foundation's International Council and hosts Tablet, a talk show on Voice of America's Persian service.

She says Iran's leaders fear women, including her. She's been called a prostitute, a whore and been falsely accused of having sexual relations with members of Iran's parliament when she worked and lived in Iran.

She's received numerous death threats, including from members of the Basij (a paramilitary volunteer militia which acts as one of the five forces of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and is designated as a terrorist organisation by the United States).

She says one of the Basij recently publicly stated: "I'm going to butcher your tongue and chest and send it to your family, and I will hire someone to do it in America".

But it's the regime's attempts to target her family and turn them against her that have caused her the most anguish.

The personal toll

Masih, whose name is short for Mashoumeh, meaning "innocent" in Farsi, was born into a conservative and religious family in Iran 45 years ago.

She divorced in her early 20s and lost custody of her son due to Iran's laws.

Her parents live in Ghomi Kola, a small village in the north, cut off from the internet and social media. They are under constant surveillance, afraid to speak to Alinejad, who says she dreams of returning to a free Iran and hugging her mother.

In 2020, the Islamic Republic also tried to coerce her 70-year-old mother into persuading Alinejad to attend a meeting in Turkey. From there, the authorities planned to kidnap her. But her brother Ali disclosed the plot to her and in doing so saved her life.

He was sentenced to eight years in prison shortly after he revealed that he had refused to cooperate with intelligence agents in luring Masih to Turkey.

In July 2018, in a New York Times article called My Sister Disowned Me on State TV she described how when she worked as a journalist in Iran she "often got into trouble exposing the regime's mismanagement and corruption until, eventually, my press pass was revoked".

"I was often threatened with arrest or worse for writing articles critical of former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Ultimately, I was forced to flee my homeland in 2009," she wrote.

But now, she says those threats were nothing compared to the abuse and attacks that began after she began the My Stealthy Freedom campaign.

"A lot of people were mocking me," she tells the ABC.

"They were attacking me. They were bullying me. Now. I see them on Twitter, sharing videos, the same videos that I have been sharing for eight years.

"It just brought tears to my eyes when one of the women said that, 'I'm very sad that I've been bullying Masih Alinejad and her campaign. But now I think she [Alinejad] was right, compulsory hijab is like the Berlin Wall'.

"And we are tearing this wall down together, in large numbers, in the streets of Iran…. This is just the beginning of the end."

'The most effective activist Iran has ever had'

Alinejad has become powerful voice outside of Iran for Iranian women and men.

She is using her massive social media following, her strong command of English and Farsi, and her connection to sell her message for regime change.

In recent years she's lobbied world leaders from Justin Trudeau to French President Emmanuel Macron.

Her strong delivery, plus the type of people she lobbies, can put her offside with some, but she has a raft of strong supporters in Iran and among the diaspora.

Karim Sadjadpour, a senior fellow with the Middle East program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, says very few of Alinejad's critics are aware of the personal costs she's paid for her beliefs.

He says she was imprisoned at age 19, expelled from her job, and eventually exiled as a young single mother who had no money and didn't speak English.

"The Islamic Republic spent over a decade defaming her, and when she refused to be silenced, they've been actively trying to eliminate her," he explains.

"She never takes a day off and I don't think she will until there is meaningful change in Iran. The Islamic Republic has tried everything it can to break her, and even kill her, but it has only made her irrepressible."

He says there are three ideological pillars left of the Islamic Republic: death to America, death to Israel, and hijab.

"Masih understood that forced hijab is the weakest pillar of the three, because not even Iran's anti-imperialist partners or fellow travellers will defend it," he says.

"People told Masih to be quiet, that hijab was a superficial issue. She understood that hijab is the flag of gender apartheid in Iran. Women don't even have the most basic freedom, to dress freely without being harassed, imprisoned, and even beaten to death."

Kaveh Shahrooz, a lawyer and human rights activist living in Canada who has also been a target of the regime, describes Alinejad as "the most effective activist Iran has ever had".

"The revolution in Iran obviously owes a lot to the courage of those, particularly the women in the streets, but Masih's work in the past few years has been the catalyst for much of it," he says.

"It created solidarity among Iranian women who began to see that the daily indignities they suffered were experienced by many others."

'Solidarity is beautiful, but it's not enough'

Alinejad, like many others, wants world governments — including Australia — to take stronger action and support protesters who for almost three months, have faced brutal force from Iran's authorities.

In that time, Iran's regime has killed more than 400 Iranians, including at least 50 children according to UNICEF, and has arrested about 15,000 protesters.

Alinejad has, via her social media accounts, been sharing images of the people she says the regime is murdering, including nine-year-old Kian Pirfalak who was shot dead while in the car with his family.

Alinejad is part of a growing global coalition calling on world leaders to pull their ambassadors out of Tehran, shut down their embassies (except for visa processing), halt nuclear deal negotiations, designate the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps as a terrorist organisation and put Iran's leaders on trial for crimes against humanity.

"This is actually the moment that the West must take strong action rather than just condemning the brutal death of Mahsa Amini or condemning the crackdown," Alinejad says.

Alienjad is disappointed that Australia continues to do business with Iran - Prime Minister Anthony Albanese declared solidarity with Iranians in parliament just weeks ago, but also said we need to support Australian businesses trading with Iran.

Foreign Minister Penny Wong has said Australia will keep working with its international partners "to increase pressure on Iran over its egregious human rights abuses" but as yet has not spoken about regime change.

"Solidarity is beautiful, but it's not enough," Alinejad says, noting that when Australia negotiates with the Islamic Republic, the regime have "no reason to stop killing, and murdering".

"You have to cut your ties with those who are killing people because of showing their hair," she says.

"You know, my heart is broken, because Nika Shahkarami was only 16 years old. She took to the streets to support Mahsa Amini. They killed her as well. Hadis Najafi was only 20 years old. The Iranian regime killed her as well."

The list goes on. "These people are not statistics," she says. "They're not numbers. They have names."

She says the Australian government can do a lot more, and it's in their interest to act.

"We are not just fighting for to protect ourselves, we are protecting the whole world from one of the most dangerous governments," Alinejad says.

"The Iranian regime provide drones to support [Russia's] massive attack happening on the Ukrainian people. So you see, as far as Islamic Republic is in power, no one's going to be safe in the world."

Iranians worldwide unite

Alinejad says Westerners who argue that regime change is not possible because there's no clear alternative leader are wrong.

"We have so many intellectual women and men, they are leading the movement, they are leading the revolution," she says.

"We have so many educated people inside and outside Iran, they can run the country better than these backward Mullahs [Muslim clergy]."

"This is the first time that left and right, people with different opinions, different political backgrounds are united. We have a united opposition, which can run the country better than the butchers [Iran's regime]."

She says the narrative of the Islamic Republic is that its Western forces that are behind the protests. They argue there is no opposition. No clear leaders to run the country. They threaten that "Iran is going to be like Syria".

"No, Iran is going to be like Germany, like Australia, like, the like any normal country in the West, because we have so many educated and intellectual leaders that can run the country better," Alinejad says.

And she notes, that apart from Iranian protests being widespread across Iran, the Iranian diaspora is also behind them, with protests all across the world.

"Even well-known athletes came out, well-known actresses have come out, and they are saying one thing: 'we want to end the gender apartheid regime'."

Alinejad often dreams of being back in Iran, and the day the mullahs are overthrown, she says she will return to hug her mother, as well as the mothers of the many children who have been killed, not just in this wave of protests, but many that have come before it.

"Those who have trusted me for years and years and allowed me to be their voices — I will go hug them; that's my dream," she says.

"And I want to hug my mum, who I haven't hugged for 13 years. I mean, I'm not a criminal. My crime is just giving a voice to voiceless people."