The night before the March on Washington, on 28 August 1963, Martin Luther King asked his aides for advice about the next day's speech. "Don't use the lines about 'I have a dream', his adviser Wyatt Walker told him. "It's trite, it's cliche. You've used it too many times already."

King had indeed employed the refrain several times before. It had featured in an address just a week earlier at a fundraiser in Chicago, and a few months before that at a huge rally in Detroit. As with most of his speeches, both had been well received, but neither had been regarded as momentous.

This speech had to be different. While King was by now a national political figure, relatively few outside the black church and the civil rights movement had heard him give a full address. With all three television networks offering live coverage of the march for jobs and freedom, this would be his oratorical introduction to the nation.

After a wide range of conflicting suggestions from his staff, King left the lobby at the Willard hotel in DC to put the final touches to a speech he hoped would be received, in his words, "like the Gettysburg address". "I am now going upstairs to my room to counsel with my Lord," he told them. "I will see you all tomorrow."

A few floors below King's suite, Walker made himself available. King would call down and tell him what he wanted to say; Walker would write something he hoped worked, then head up the stairs to present it to King.

"When it came to my speech drafts," wrote Clarence Jones, who had already penned the first draft, "[King] often acted like an interior designer. I would deliver four strong walls and he would use his God-given abilities to furnish the place so it felt like home." King finished the outline at about midnight and then wrote a draft in longhand. One of his aides who went to King's suite that night saw words crossed out three or four times. He thought it looked as though King were writing poetry. King went to sleep at about 4am, giving the text to his aides to print and distribute. The "I have a dream" section was not in it.

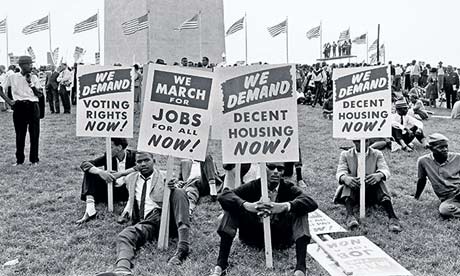

A few hours after King went to sleep, the march's organiser, Bayard Rustin, wandered on to the Washington Mall, where the demonstration would take place later that day, with some of his assistants, to find security personnel and journalists outnumbering demonstrators. Political marches in Washington are now commonplace, but in 1963 attempting to stage a march of this size in that place was unprecedented. The movement had high hopes for a large turnout and originally set a goal of 100,000. From the reservations on coaches and trains alone, they guessed they should be at least close to that figure. But when the morning came, that expectation did little to calm their nerves. Reporters badgered Rustin about the ramifications for both the event and the movement if the crowd turned out to be smaller than anticipated. Rustin, forever theatrical, took a round pocket watch from his trousers and some paper from his jacket. Examining first the paper and then the watch, he turned to the reporters and said: "Everything is right on schedule." The piece of paper was blank.

The first official Freedom Train arrived at Washington's Union station from Pittsburgh at 8.02am, records Charles Euchner in Nobody Turn Me Around. Within a couple of hours, thousands were pouring through the stations every five minutes, while almost two buses a minute rolled into DC from across the country. About 250,000 people showed up that day. The Washington Mall was awash with Hollywood celebrities, including Charlton Heston, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis Jr, Burt Lancaster, James Garner and Harry Belafonte. Marlon Brando wandered around brandishing an electric cattle prod, a symbol of police brutality. Josephine Baker made it over from France. Paul Newman mingled with the crowd.

It was a hectic morning for King, paying a courtesy visit with other march leaders to politicians at the Capitol, but he still found time to fiddle with the speech. When he eventually walked to the podium, the typed final version was once more full of crossings out and scribbles.

Rustin had limited the speakers to just five minutes each, and threatened to come on with a crook and haul them from the podium when their time was up. But they all overran and, given the heat – 87F at noon – and humidity, the crowd's mood began to wane. Weary from a night's travel, many were anxious to make good time on the journey back and had already left. King was 16th on an official programme that included the national anthem, the invocation, a prayer, a tribute to women, two sets of songs and nine other speakers. Only the benediction and the pledge came after. Portions of the crowd had moved off to seek respite from the heat under the trees on the Mall while others dipped their feet in the reflecting pool. Those most eager for a view of the podium braved the sun under the shade of their umbrellas.

"There was… an air of subtle depression, of wistful apathy which existed in many," wrote Norman Mailer. "One felt a little of the muted disappointment which attacks a crowd in the seventh inning of a very important baseball game when the score has gone 11-3. The home team is ahead, but the tension is broken: one's concern is no longer noble."

But if they were exhausted, they were no less excited. Gospel singer Mahalia Jackson had lifted spirits with I've Been 'Buked and I've Been Scorned. Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress, followed, recalling his time as a rabbi in Berlin under Hitler: "A great people who had created a great civilisation had become a nation of silent onlookers. They remained silent in the face of hate, in the face of brutality and in the face of mass murder," he said. "America must not become a nation of onlookers. America must not remain silent."

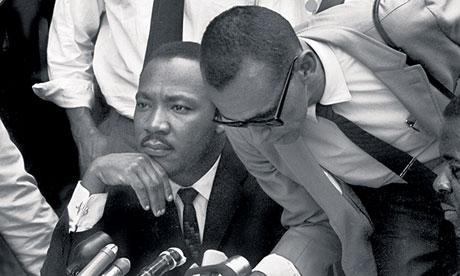

King was next. The area around the mic was crowded with speakers, dignitaries and their entourages. Wearing a black suit, black tie and white shirt, King edged through the melee towards the podium.

"I tell students today, 'There were no jumbotrons [large screen TVs] back then,' " says Rachelle Horowitz, the young activist who organised transport to the march. "All people could see was a speck. And they listened to it."

King started slowly, and stuck close to his prepared text. "I thought it was a good speech," recalled John Lewis, the leader of the student wing of the movement, who had addressed the march earlier that day. "But it was not nearly as powerful as many I had heard him make. As he moved towards his final words, it seemed that he, too, could sense that he was falling short. He hadn't locked into that power he so often found."

King was winding up what would have been a well-received but, by his standards, fairly unremarkable oration. "Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana," he said. Then, behind him, Mahalia Jackson cried out: "Tell 'em about the dream, Martin." Jackson had a particularly intimate emotional relationship with King, who when he felt down would call her for some "gospel musical therapy".

"She was his favourite gospel singer, and he would ask her to sing The Old Rugged Cross or Jesus Met The Woman At The Well down the phone," Jones explains. Jackson had seen him deliver the dream refrain in Detroit in June and clearly it had moved her.

"Go back to the slums and ghettoes of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed," King said. Jackson shouted again: "Tell 'em about the dream." "Let us not wallow in the valley of despair. I say to you today, my friends." Then King grabbed the podium and set his prepared text to his left. "When he was reading from his text, he stood like a lecturer," Jones says. "But from the moment he set that text aside, he took on the stance of a Baptist preacher." Jones turned to the person standing next to him and said: "Those people don't know it, but they're about to go to church."

A smattering of applause filled a pause more pregnant than most.

"So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream."

"Aw, shit," Walker said. "He's using the dream."

For all King's careful preparation, the part of the speech that went on to enter the history books was added extemporaneously while he was standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, speaking in full flight to the crowd. "I know that on the eve of his speech it was not in his mind to revisit the dream," Jones insists.

It is open to debate just how spontaneous the insertion of the "I have a dream" section was (Euchner says a guest in the adjacent hotel room to King heard him rehearsing the segment the night before), but the two things we know for sure are that it was not in the prepared text and it wasn't invented on the spot. King had been using the refrain for well over a year. Talking some months later of his decision to include the passage, King said: "I started out reading the speech, and I read it down to a point. The audience response was wonderful that day… And all of a sudden this thing came to me that… I'd used many times before… 'I have a dream.' And I just felt that I wanted to use it here… I used it, and at that point I just turned aside from the manuscript altogether. I didn't come back to it."

"Though [King] was extremely well known before he stepped up to the lectern," Jones wrote, "he had stepped down on the other side of history."

Watching the whole thing on TV in the White House, President John F Kennedy, who had never heard an entire King speech before, remarked: "He's damned good. Damned good." Almost everyone, including even King's enemies, recognised the speech's reach and resonance. William Sullivan, the FBI's assistant director of domestic intelligence, recommended: "We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous negro of the future of this nation."

A few in the crowd were unimpressed. Anne Moody, a black activist who had made the trip from rural Mississippi, recalled: "I sat on the grass and listened to the speakers, to discover we had 'dreamers' instead of leaders leading us. Just about every one of them stood up there dreaming. Martin Luther King went on and on talking about his dream. I sat there thinking that in Canton we never had time to sleep, much less dream."

But most were ebullient. "It would be like if, right now in the Arab spring, somebody made a speech that was 15 minutes long that summarised what this whole period of social change was all about," one of King's most trusted aides, Andrew Young, told me. "The country was in more turmoil than it had been in since before the second world war. People didn't understand it. And he explained it. It wasn't a black speech. It wasn't just a Christian speech. It was an all-American speech."

Fifty years on, the speech enjoys both national and global acclaim. A 1999 survey conducted by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Texas A&M University, of 137 leading scholars of public address, named it the greatest speech of the 20th century.

During the protests in Tiananmen Square, China, some protesters held up posters of King saying "I have a dream". On the wall that Israel has built around parts of the West Bank, someone has written "I have a dream. This is not part of that dream." The phrase "I have a dream" has been spotted in such disparate places as a train in Budapest and on a mural in suburban Sydney. Asked in 2008 whether they thought the speech was "relevant to people of your generation", 68% of Americans said yes, including 76% of blacks and 67% of whites. Only 4% were not familiar with it.

But few of those in the movement thought at the time that it would be the speech by which King would be remembered 50 years later.

"Rustin always said that King's genius was that he could simultaneously talk to a black audience about why they needed to achieve their freedom and address a white audience about why they should support that freedom," recalls Horowitz. "Simultaneously. It was a genius that he could do that as one Gestalt… King's was the poetry that made the march immortal. He capped off the day perfectly. He did what everybody wanted him to do and expected him to do. But I don't think anybody predicted at the time that the speech would do what it did since."

Their bemusement was justified. For if, in its immediate aftermath, the speech had any significant political impact, it was not obvious. "At the time of King's death in April 1968, his speech at the March on Washington had nearly vanished from public view," writes Drew Hansen in his book about the speech, The Dream. "There was no reason to believe that King's speech would one day come to be seen as a defining moment for his career and for the civil rights movement as a whole… King's speech at the march is almost never mentioned during the monumental debates over the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which occupy around 64,000 pages of the Congressional record."

History does not objectively sift through speeches, pick out the best on their merits and then dedicate them faithfully to public memory. It commits itself to the task with great prejudice and fickle appreciation, in a manner that tells us as much about the historian and the times as the speech itself. The speech was marginalised because, in the last few years of his life, King himself was marginalised, and few who had the power to elevate his speech to iconic status had any self-interest in doing so. His growing propensity to take on issues of poverty, followed by his opposition to the Vietnam war, lost him the support of the political class and much of his white and more conservative base.

King's speech at the March on Washington offers a positive prognosis on the apparently chronic American ailment of racism. As such, it is a rare thing to find in almost any culture or nation: an optimistic oration about race that acknowledges the desperate circumstances that made it necessary while still projecting hope, patriotism, humanism and militancy.

In the age of Obama and the Tea Party, there is something in there for everyone. It speaks, in the vernacular of the black church, with clarity and conviction to African Americans' historical plight and looks forward to a time when that plight will be eliminated ("We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating 'for whites only'. No, no, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream").

Its nod to all that is sacred in American political culture, from the founding fathers to the American dream, makes it patriotic ("I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed, 'We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'"). It sets bigotry against colour-blindness while prescribing no route map for how we get from one to the other. ("I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists… little black boys and little black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.")

But the breadth of its appeal is to some extent at the expense of depth. It is in no small part so widely admired because the interpretations of what King was saying vary so widely. Polls show that while African Americans and American whites both agree about the extent to which "the dream has been realised", they profoundly disagree on the state of contemporary race relations. The recent acquittal of George Zimmerman over the shooting of the black teenager Trayvon Martin illustrates the degree to which blacks and whites are less likely to see the same problems, more likely to disagree on the causes of those problems and, therefore, unlikely to agree on a remedy. Hearing the same speech, they understand different things.

Conservatives, meanwhile, have been keen to co-opt both King and the speech. In 2010, Tea Party favourite Glenn Beck held the "Restoring Honour" rally at the Lincoln Memorial on the 47th anniversary of the speech, telling a crowd of about 90,000: "The man who stood down on those stairs… gave his life for everyone's right to have a dream." Almost a year later, black republican presidential candidate Herman Cain opened his speech to the southern Republican leadership conference with the words, "I have a dream."

Their embrace of the speech has made some black intellectuals and activists wary. They fear that the speech can too easily be distorted in a manner that undermines the speaker's legacy. "In the light of the determined misuse of King's rhetoric, a modest proposal appears in order," Georgetown university professor Michael Dyson wrote in 2001. "A 10-year moratorium on listening to or reading 'I Have a Dream'." At first blush, such a proposal seems absurd and counter- productive. After all, King's words have convinced many Americans that racial justice should be aggressively pursued. The sad truth is, however, that our political climate has eroded the real point of King's beautiful words."

These responses tell us at least as much about now as then, perhaps more. The 50th anniversary of "I have a dream" arrives at a time when the president is black, whites are destined to become a minority in the US in little more than a generation, and civil rights-era protections are being dismantled. Segregationists have all but disappeared, even if segregation as a lived experience has not. Racism, however, remains.

Fifty years on, it is clear that in eliminating legal segregation – not racism, but formal, codified discrimination – the civil rights movement delivered the last moral victory in America for which there is still a consensus. While the struggle to defeat it was bitter and divisive, nobody today is seriously campaigning for the return of segregation or openly mourning its demise. The speech's appeal lies in the fact that, whatever the interpretation, it remains the most eloquent, poetic, unapologetic and public articulation of that victory. •

• Adapted from The Speech: The Story Behind Martin Luther King's Dream, by Gary Younge, published on 22 August by Guardian Books at £6.99. To order a copy for £5.59, including mainland UK p&p, go to theguardian.com/bookshop or call 0330 333 6846.