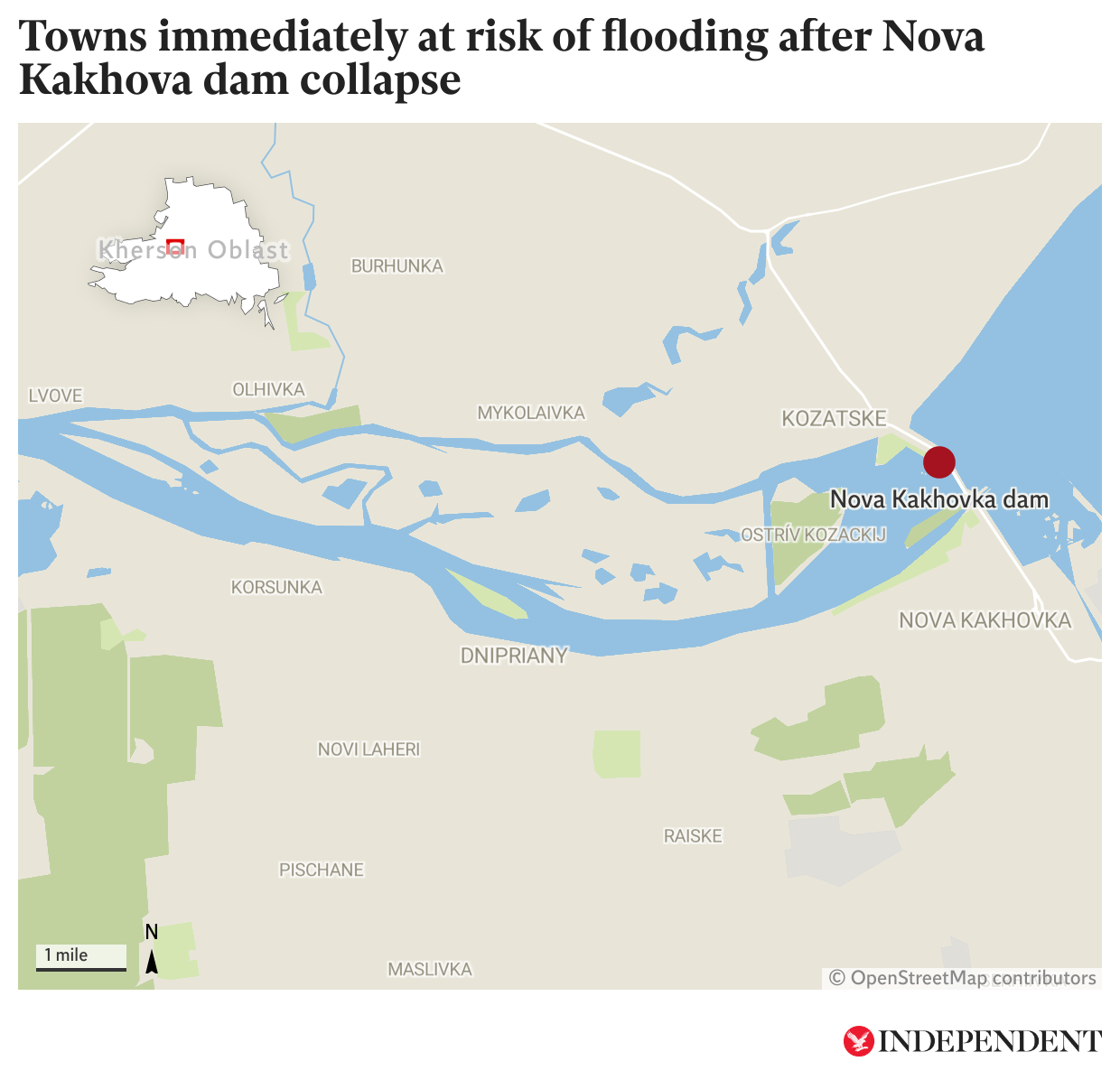

War-torn Ukraine is reeling from the collapse of the Nova Kakhovka hydroelectric dam, which saw its reservoir burst causing chaos for miles around.

The catastrophe on Tuesday 6 June forced thousands of residents of nearby towns and villages to evacuate their homes as the floodwater barrelled towards them and left some climbing onto rooftops or into trees to escape the raging torrents.

Hundreds of thousands more have been left without access to clean drinking water in the region as a result of the eco-disaster on the Dnipro River, prompting relief workers to rush fresh supplies to the area as they struggle with the problems of mass resettlement.

While the official tallies reported that over 2,700 people fled the flooded areas on both the Ukrainian and Russian-controlled sides of the river in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, a fuller picture has yet to emerge given that more than 60,000 people live in the vicinity.

Kyiv has blamed Russia for deliberately destroying the Soviet-era infrastructure, with Moscow, inevitably, protesting its innocence and contemptuously suggesting that Ukrainian saboteurs are responsible.

Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky has called the incident “a war crime” and the “largest man-made environmental disaster in Europe in decades”.

He visited the flooded city of Kherson two days after the catastophe, only for Russian forces to begin shelling the area almost immediately.

That tactic has been seen again this week in the city of Nova Kakhovka itself and the nearby village of Plodovoye, with at least one person killed in an attack on a beleagured residential area.

Russia would certainly appear to have the most to gain from the dam disaster and President Zelensky did warn as long ago as last November that he believed enemy soldiers had mined the dam and were plotting its destruction. He reiterated that stance in a tweet on Tuesday: “It is physically impossible to blow it up somehow from the outside, by shelling. It was mined by the Russian occupiers. And they blew it up.”

For now though, the priority remains coming to the aid of the stricken people of Kherson.

Ukraine’s deputy prime minister Oleksandr Kubrakov has warned of the threat to their wellbeing posed by hazardous chemicals and infectious diseases carried by the water as well as from landmines previously placed near the war’s frontline, which have been disturbed by the floods and are now likely to explode.

The water in the reservoir feeds a wide area of southern Ukrainian farmland, including the annexed peninsula of Crimea, as well as providing all-important cooling water to the Russian-held Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant, lying nearby as indicated on the map below.

A United Nations nuclear watchdog has attempted to reassure the public by saying that there is “no immediate risk” to the plant, even if it were to run out of water for its cooling systems.

There is no such good news for the region’s farmers, however, with the flooding expected to spell instant disaster for this year’s harvest: crops are likely to be washed away, fields left waterlogged and livestock drowned in water that is at serious risk of being contaminated by machine oil, already seen gushing into the Dnipro.

The depleted reservoir is also considered unlikely to be able to supply adequate irrigation to the surrounding fields for several years to come, a huge setback for Ukraine’s eventual hopes of economic recovery.

All of which is also likely to have consequences for a global food market that has increasingly relied upon Ukraine for the supply of agricultural produce since the end of the Cold War.

“There is no doubt that this will lead to large-scale environmental, economic and human consequences,” Mykhailo Podolyak, a chief adviser to President Zelensky, told The Independent.

“The instantaneous death of a large number of fish and animals, the waterlogging of drained lands, and the change in the climatic regime of the region, will later be reflected in the food security of the world.

“A one-time reduction of water in a huge reservoir will lead to unpredictable ecological consequences.”

Mr Podolyak warned that he expected the floodwaters to reach Mykolaiv, lying 56 miles from the dam and decried the drowning of the entire population of animals at the Kazkova Dibrova zoo on the Russian-held eastern bank of the river as particularly tragic.

President Zelensky has already rebuked the officials installed by Moscow to run occupied territories along that bank for failing to respond adequately to the emergency.

The Russian authorities he criticised have conceded that they evacuated fewer than 1,300 people in the first days of the catastrophe in an area where as many as 40,000 people were said to be affected.

That compared unfavourably with the estimated 1,700 evacuated on the Ukrainian side to the west, where the population was reportedly around 42,000.

According to the independent Russian news outlet Vyorstka, residents of the Moscow-run village of Oleshky, for one, remain stranded, the publisher quoting one woman as saying that her mother, who could not make it to the roof, was in the water clutching a ladder.

A volunteer confirmed to Vyorstka that those still awaiting evacuation included children and disabled people.

Civilians in Kherson were seen clutching personal belongings as they waded through knee-deep water in the streets and rode rubber rafts.

Video on social media showed rescuers carrying others to safety and what looked like the triangular roof of a building floating downstream.

Aerial footage showed flooded streets in the Russian-controlled Nova Kakhovska, where Mayor Vladimir Leontyev said seven people were missing, although they were believed to be alive.

But perhaps most striking of all has been the aerial shots of the region captured by Maxar Technologies, which give the fullest picture of the damage done seen so far.

The UK is among the ally nations pledging additional humanitarian aid to help Ukraine address the crisis, promising £16 million in donations.

Additional reporting by agencies