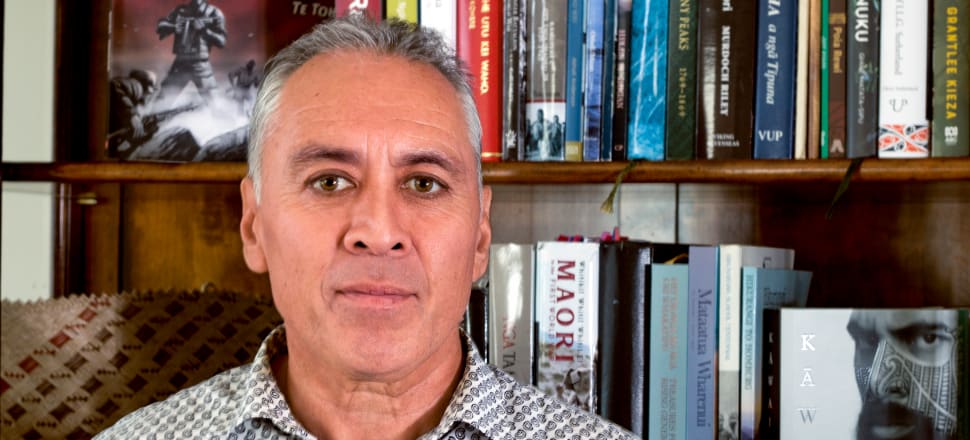

A Māori scholar touches on "a difficult history"

My new novel Kāwai portrays Maori society in the 1700s and kaitangata - referred to as cannibalism in ethnographic literature - was very much a part of that society. To ignore it in the novel would be to be unfaithful to what I know about this period.

Cannibalism has its own life in the historiography which emanates from Europe. It doesn’t necessarily convey deeper Māori understandings of the term. But while Kāwai does not shy away from difficult history, I must remind the reader that this scene is taken from a novel. Yes, the novel is based on many true stories, but it’s still a work of fiction..

Why did I include kaitangata in the novel? Because it was what it was. I have a research background that spans almost 40 years, in which time I have had access to closely guarded tribal and family manuscripts. In my early adult life, I had a research job which required me to read volumes of evidence recorded in the original minute books of the Native Land Court. These had been scribed in the last three decades of the 19th century. They captured statements by exemplars of the culture, many of whom were in their 70s and 80s.

At the time, I was also part of a group privy to the oral traditions of our people. Our elders, some of whom were veterans of the 28th Māori Battalion, spoke to us knowing that we had been raised in the same cultural value system as they, and that they had a cultural obligation to teach us our history without cherry-picking, for what they carried were the last vestiges of our connection to the Hawaiki homeland. We were shown places on our rural landscape named ‘Umu-a-so-and-so’, which meant ‘where so-and-so was cooked’. In one unused paddock, lies an enormous disc-shaped rock named ‘umu-tangata’ (earth oven of people) which we were warned away from, because human flesh had been often cut up on it. Such relics and their associated korero made the past far closer than we realised.

One knowledgeable elder once told us about a bed-ridden old man or koroua, who in the elder’s youth had asked him to fetch some kina (sea eggs) from the sea. While sorting the tongues of the kina the koroua directed him to separate out the redder looking ones and to leave them for those who had tasted human flesh. By that he meant himself. This was in the 1910s. The koroua was probably born in the 1830s when the custom was still practiced.

All these sources captured evidence of kaitangata, some far more horrific, if judged from today’s perspective, than anything I have described in the novel.

For young men as we were, the products of Māori boarding schools, used to seeing and assisting in farm kills, it was not with revulsion that we received these accounts, but rather with an acceptance that they were part of our past culture, before our ancestors had turned to Christianity, and we made no judgments of them.

Some commentators have written that Māori never pursued the practice from love of it, but to gratify revenge on enemies. That may be true, but there are instances in our oral traditions which point to the killing and consuming of individuals who were less than traditional enemies. Uenuku, for example, on learning that his wife had committed adultery, dispatched her, cooked her heart and fed it to their child, Ira, who became known as Ira-kai-putahi (Ira-eater-of-hearts). I guess it depends on how you define the term enemy or hoariri as one would say it in Maori (angry friend).

Pononga, which I reluctantly translated in the novel as slaves, were sometimes killed for important events like the construction of a house or the tattooing of a high-ranking male or female. Pononga were in fact enemies taken in battle or raids and forced into roles of servitude. So, somewhere between servant and slave might be closer to the mark.

The scene quoted below is one of a handful in the narrative where kaitangata is touched on. Taken on its own, it can give the wrong impression of what the novel is about and detract from all the other cultural aspects which the book reveals. Most New Zealanders see only token bits of that culture on show today and are probably totally unaware of how they were used before Aotearoa was colonised.

*

Pages 45-48 of Kāwai, by Monty Soutar: The chief walked among his people regularly over the next few days, offering an encouraging word here and there. The fruits of their hard work could be seen all about Ngāpō. Temporary sleeping quarters had been erected; parties of older women were making floor mats, baskets and plates from harakeke; while young girls scraped the flax leaves with mussel shells and, along with their mothers, wove garments from the remaining fibre to offer as gifts for the baby. A shell was a clumsy tool in the hands of a novice, but marvellously efficient in the deft fingers of the more experienced. The boys were collecting rubbish while their fathers chopped wood.

Knowing that they would all have a small part in raising his son, the workers cheerfully addressed the young chief as he walked past.

"Tēnā koe i tā tātau tamaiti, e Rangi." Greetings on the birth of our child, oh Chief.

Out of earshot they discussed the baby’s name. "I bet it will be something to do with Te Maniaroa," one woman suggested.

"No, their daughter has that covered," said another.

"It will be Kū, I’m sure," a third woman postulated. "You watch — he’ll name him after his father."

"What about Kiri’s father?" another woman said. "Surely she’ll want his name on their child."

"It’s up to him. It will be his father’s name for sure. It will be Kū." Tāwae was eager to examine the varieties of fish that were suspended from the trees to dry. He saw hāpuku, tāmure, tarakihi, kahawai and even shark carcasses. All had been caught by the men observing the rhythms of the moon and offering up the appropriate invocation to Tangaroa, the atua of the sea.

The chief cook was overseeing a group of pononga who were busily removing the backbones, heads and tails from eels and hanging them on mānuka railings to dry. Tāwae could almost taste the sweet, succulent meat.

"Over five nights," the cook told him, "we’ve caught almost four hundred tuna, with one large hīnaki still to be emptied." Tāwae opened the lid of the wicker basket and salivated at the sight of dozens of slimy, black, silver-bellied eels, slithering over, under and around one another.

A couple of other pā had sent supplies of taro, a starchy foodstuff reserved for important people, while others sent kete of sweet kūmara. The only delicacies missing from the menu were kererū and kākā preserved in their own fat, as it was not the season for bird-fowling.

The kīnaki or relish was to be provided by an unsuspecting pononga, and this time Wehe did the honours himself. While some of the kai-rākau watched, he silently walked up behind a female slave who was crouched over a large smooth stone making dough patties from pounded fernroot. Taking his patu from his belt, Wehe struck her swiftly across the back of her skull, the blunt force he used ensuring a sharp, clean fracture. The woman slumped forward, her lank hair soon saturated with blood.

Turning to the pononga’s companions, Wehe bellowed, "If I catch anyone else stealing from the kūmara pits you can expect the same treatment. You two, pick her up and take her to the cooking area." The servants scurried over and collected the body. Wehe then drew alongside the three remaining pononga. The men didn’t look up but pounded their fernroot harder and harder.

"No good, eh?" One of the pononga said quietly to his companions, his shaggy hair hiding his eyes, which were fixed on Wehe’s feet. Wehe stood motionless for a moment, still clenching his patu. "Ehara te kupu i te papaki mō te pononga: ahakoa hoki ia mātau, e kore ia e rongo," he said over his shoulder to the kai-rākau. Sometimes slaves cannot be disciplined by mere words. Though they understand, they won’t respond.

The trembling pononga before him didn’t know whether he was next for the earth oven or if his master was just admiring his work. Wehe slid his patu back into his belt and walked off, just as a trail of urine made its way out from under the pononga’s flax kilt.

The chief cook, a ferocious-looking character, was waiting with his own group of workers and pononga for the tohunga’s two apprentices to complete their invocation over the slain body. As soon as they finished their karakia, Wehe barked instructions to the cook.

"Make sure it’s not overdone like last time."

The cook glared back at him.

Wehe and the kai-rākau watched as the two pononga laid the body on a large rock slab. Thwack! Thwack! Thwack! The adze did its work and the head rolled away. The dogs, which had gathered instantly at the scent of blood, began licking the severed neck. The legs and arms were chopped off at the joints and two women skilfully boned the thighs before wrapping them in leaves and placing them in a basket, which was covered to stop flies getting at them.

"E tā! For goodness’ sake!" the cook snarled as he threw the bones to the dogs. "Just the one, Wehe? That won’t be enough."

"It’s for the visiting chiefs, not us," Wehe fired back. "Why don’t you slaughter a couple of those kurī and cook them in the umu too?"

"Ha! Then what will keep me warm when the cold nights arrive? I need my dogs," the cook chortled. "A warrior can survive on water and fernroot if need be," one of the kai-rākau chipped in. "We’re not sure about you though, Cookie — seems like you eat all the time."

As the pononga was about to put the last limb in the basket the cook grabbed it, poked out his tongue and pretended to lick it. Then he closed his eyes and smiled to indicate extreme pleasure. The kai-rākau couldn’t contain their mirth, while the other pononga kept their eyes cast down. "The main thing is hospitality," Wehe said. "Making sure we have a variety of food at the feast, and more than enough to send our relatives home satisfied."

The cook could see his workers and the pononga were handling the torso with reluctance.

"Here, I’ll do it," he growled as he nudged them aside. Wehe’s men observed with interest as the cook displayed his impressive butchering techniques using an obsidian knife and long-handled adze. The torso was quartered, the entrails removed and fed to the dogs, whose powerful jaws tore at them while their bushy tails wagged wildly.

"You have an easy job," one of the kai-rākau teased. The cook wiped perspiration from his forehead. "This is easy work? Here, you try it." He offered the warrior the knife and stood aside, his muscular arms decorated with sweat, blood and visceral fat. The kai-rākau seemed reluctant to take up the challenge.

"Ah . . . no thanks. Really, you’re doing fine." His mates teased him, while the cook grinned.

"Back to work, men." Wehe clapped and the kai-rākau departed, leaving the cook’s helpers washing the body parts in a stream of fresh water.

Kāwai: For such a time as this by Monty Soutar (Bateman, $40) is available in bookstores nationwide. It will be launched tomorrow (Tuesday, September 13) at the Ellen Melville Hall, 2 Freyberg Place, Auckland, from 6pm.