It is common to meet someone who believes that all of their assets should be in equities, even in retirement. The rationale is that, over the long term, equities tend to be one of the best places for growth, which is true. However, these claims often point to long-term averages, which, when you dive a little deeper into the application, can be misleading.

This article is intended to address two major arguments. The first is that averages are a great tool to use when you are planning your retirement, but there’s more that needs to be addressed. The second is that the markets have a history of going flat for 10-plus years every 20 years or so, which can create some serious problems in retirement.

My intention in writing this article is to help raise your awareness of certain risks while inviting you to think outside the box and consider a more balanced and deliberate approach to your retirement income planning and portfolio management. Let’s dive in.

Averages can be deceptive

If you had an account with $100,000 and expected that account to grow, on average, about 10%, then you would probably expect the following to happen:

- Year 0: $100,000

- Year 1: $110,000 (10% gain)

- Year 2: $121,000 (10% gain)

However, the markets are often not that consistent. For example, if you experienced a 20% loss and a 30% gain, you would still average a 10% return year over year, but you’d get a very different outcome.

- Year 0: $100,000

- Year 1: $80,000 (20% loss)

- Year 2: $104,000 (30% gain)

You may be thinking I’m rigging the math to prove a point by putting the 20% loss in year one. Let’s reverse it and see what happens.

- Year 0: $100,000

- Year 1: $130,000 (30% gain)

- Year 2: $104,000 (20% loss)

The volatility (ups and downs) matters. Taking a simple average and projecting the growth of your accounts may be problematic. This is especially true if we enter into a flat market cycle.

The flat market cycle can be rough

Historically speaking, the markets have gone flat (zero return over a period of time) for 10 years every 20 years or so. Some of the more notable flat markets over the past 100 years started in 2000, 1966 and 1929. (For more on this, see my article Four Historical Patterns in the Markets for Investors to Know).

If you put all of your assets in equities and follow the 4% rule (take 4% out of your portfolio as income each year), then you may find yourself in a difficult situation if the markets go into another flat cycle.

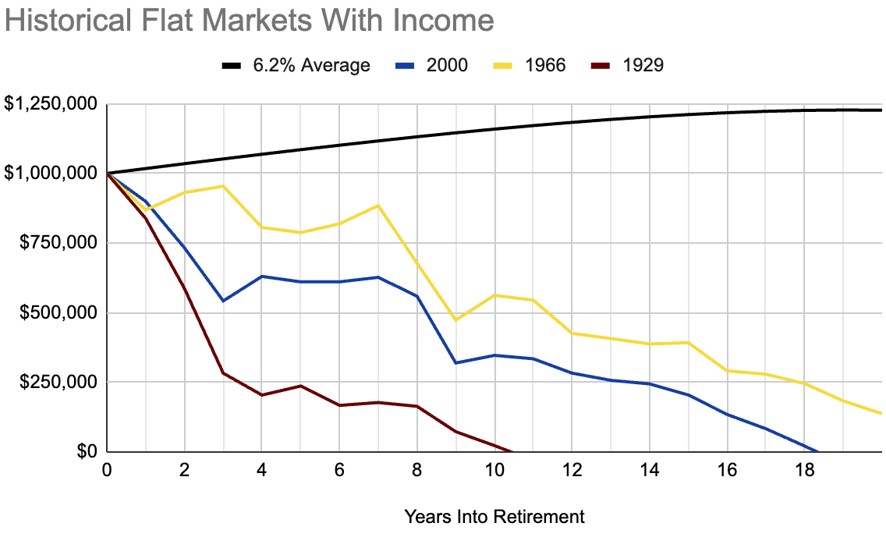

For context, the average return from 2000 through 2020 was about 6% to 7%. The same is true for the average return from 1966 through 1986. We will omit the 1929 average because it is significantly worse. So, assuming we take a conservative average return of 6% and draw only 4% from our portfolio, the averages would suggest that we should be fine (see the black line in the graph below).

However, if we account for the ups and downs in a flat market cycle, there’s a very different story to be told. For reference, this risk is often referred to as sequence of returns risk. See below what would have happened had you started with the same amount of assets while pulling the same amount of income but started your retirement at the beginning of one of the three historical flat market cycles.

Notice how each example has significantly less money left in the account than the “conservative 6% average” expectation. Many people could be retired for 30 years. If that is the case, and the historical flat market pattern continues, then it would be reasonable to guess that there could be a flat market cycle in your retirement. Are you prepared?

No one knows the future of the market. We could be in a flat market right now. Creating a retirement income plan based on averages when all of your assets are at risk in the equities market may not be in your best interest. How you pull income each year, especially during the first 10 years of your retirement, may matter more than your long-term average expectation.

If you feel like maybe you have too much exposure to equities, consider moving some of your assets into less risky investments or products. Many financial professionals would recommend you buy an annuity and then annuitize it into lifetime income.

I recommend using something I call a Principal Guaranteed Reservoir™, which I discuss in my book, How to Retire on Time. The idea is to have some assets in accounts that offer principal protection so that when the markets go down, you can draw income from your reservoir while you allow your other accounts to recover. This helps avoid sequence of returns risk without locking up assets for life in annuitized income.

Regardless of which way you go, remember, there’s no such thing as a perfect investment or investment strategy. It is important to put a plan together and then design your portfolio to support that plan.