When Seth Kinast started taking an experimental male birth control, his energy levels shot up. He no longer crashed in the afternoon and his sex drive improved dramatically.

“We joke that it was like he was a teenager again,” says Caitlin Kinast, Seth’s partner.

Caitlin Kinast, a 34-year-old full-time mother of two in suburban Seattle, stopped using all hormonal birth control after suffering a bilateral pulmonary embolism in 2013. After the birth of her and Seth’s first child in 2018, she got a copper IUD, but that gave her “periods on steroids,” she says.

When she and Seth learned about a clinical trial for male birth control in May 2019, they leaped at the opportunity.

Seth, 34, a software engineer, spent 16 months on the new birth control, which comes in a gel that users apply to their back. It’s called NES/T (“nes-tee”) after its two components, nestorone and testosterone.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is in the final year of enrollment of NES/T’s Phase 2 clinical trial, which began in 2018 and involves about 420 monogamous couples at 15 sites around the world. It’s estimated to be completed in 2023 or 2024 with a Phase 3 trial beginning soon after. The participants use the gel as their only form of birth control for a year. If the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves this progress, NES/T will become the first hormonal male contraceptive to enter Phase 3 clinical trials.

To say it has been a long time coming is an understatement. There’s a glaring lack of reliable reversible contraceptives for men* while a buffet of pills, patches, implants, and more are available to women**, along with their myriad side effects. Right now, men have just two birth control options, both non-hormonal: condoms and vasectomy. One of those has an 85 percent effectiveness rate, and many people choose to forego it. The other one is a permanent surgical procedure.

On June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, effectively ending Americans’ constitutional right to abortion. With safe, legal abortion no longer available to all Americans, everyone deserves a tool to create responsible sexual partners in pregnancy prevention. What has it taken so long and are we close to an effective and safe male birth control?

*Those who produce sperm — while women and men will be shorthand for these terms in this piece, some men don’t produce sperm, have XY chromosomes, or two testicles, and some women don’t ovulate, have XX chromosomes, or a uterus — whether they’re queer, intersex, and/or have a condition that affects their reproductive traits.

**Those who ovulate.

A history of birth control

For many, the name Margaret Sanger is synonymous with birth control. A first-wave feminist, Sanger opened the country’s first birth control clinic in 1916. In the 1940s and ‘50s, she followed the scientific development of birth control, throwing her weight and money behind research efforts. In 1960, the FDA approved the sale of an oral contraceptive. By 1965, 25 percent of married women under 45 had tried it, signaling a new era for women having greater power over their reproductive system.

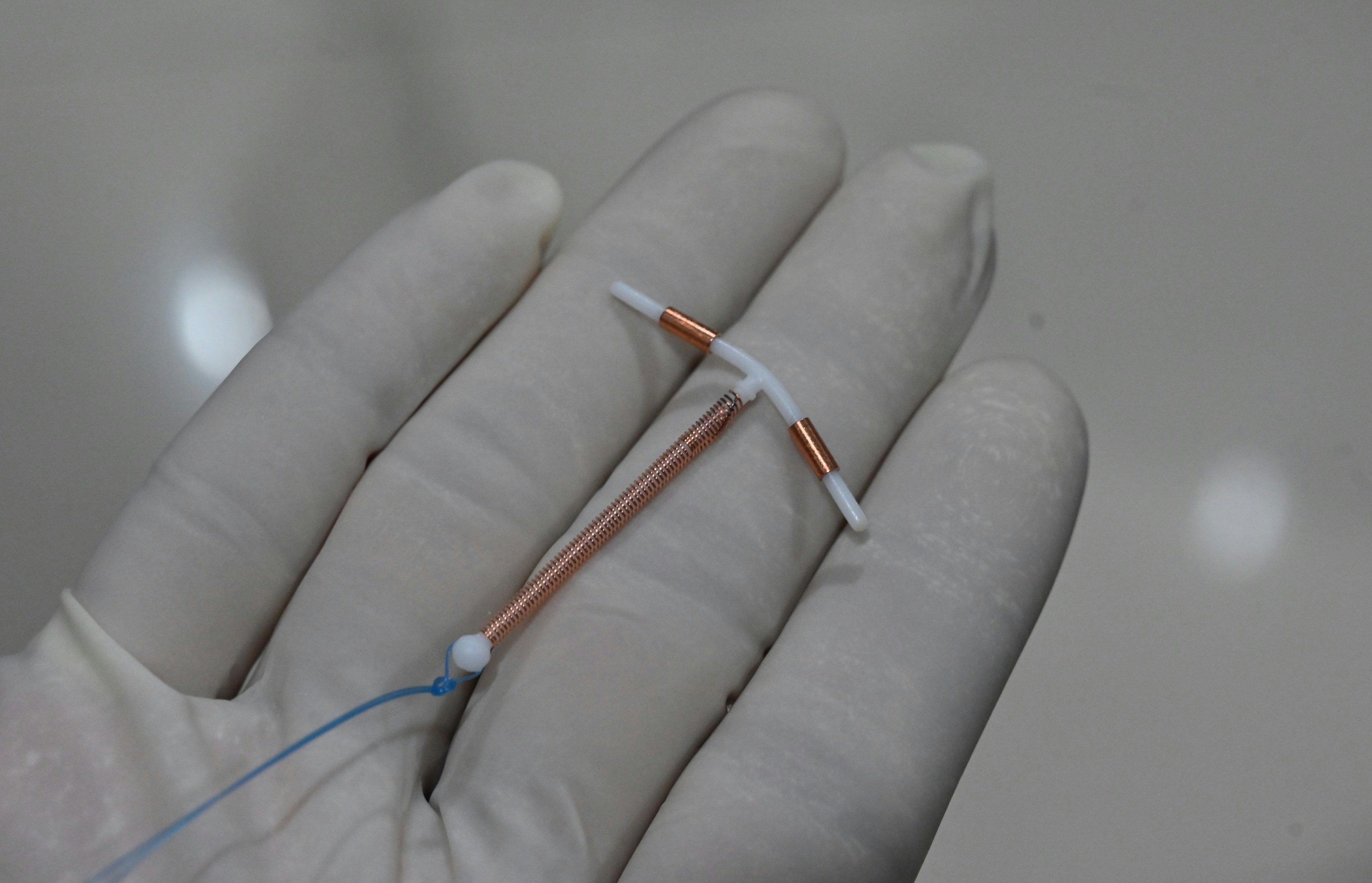

(Hormonal contraceptives are any methods that release hormones to alter the body’s reproductive cycle. Patches, pills, implants, injections, vaginal rings, and hormonal IUDs are all hormonal birth control. Non-hormonal methods such as condoms, the sponge, copper IUDs, spermicide, cervical caps, and diaphragms physically prevent the sperm from fertilizing the egg without changing the body.)

It might come as a surprise that research behind hormonal male birth control is about as old as the pill. Over the past few decades, there have been a few promising reversible non-hormonal candidates, such as RISUG, which stands for Reversible Inhibition of Sperm Under Guidance. Developed in India in the 1970s, this contraceptive is a gel polymer injected to temporarily block sperm from the vas deferens (the duct that carries sperm to the urethra). A similar product, Vasalgel, is being studied in the United States by Revolution Contraceptives. There’s also a pill currently known as YCT529, which has prevented pregnancy in mice by disabling a vitamin A receptor, temporarily sterilizing males. Researchers may begin trials on this drug as early as the end of 2022.

Pharmaceutical companies have a built-in market for female contraceptives, but choosing to forego male birth control altogether could seal a door they haven’t even opened.

Today, it takes a long time for most drugs to reach the market. For contraceptives, in particular, it takes about 25 years, John Townsend, chair of the Population Council’s ethical review board, tells Inverse. That encompasses getting it through three clinical trial stages, passing regulatory requirements, and then bringing it to market. The Population Council, a reproductive health non-profit collaborated in and helped fund the NES/T trial.

NES/T has been in the works for at least eight years. The male contraceptive gel combines two existing hormones: testosterone and segesterone acetate (a synthetic progesterone, or progestin), aka nestorone. Doctors regularly prescribe testosterone gel for those with hypogonadism, meaning they have naturally low testosterone levels. A vaginal ring already uses nestorone as hormonal birth control. The two of them form a hand sanitizer-like gel that’s absorbed through the skin over two hours.

Once absorbed, the nestorone modifies the production of hormones called gonadotropins that come from a pea-sized gland in the brain called the pituitary gland. The nestorone suppresses the creation of two specific gonadotropins called follicle-stimulating hormone, which promotes sperm creation — of which men create about 20 to 30 million per day — and luteinizing hormone, which stimulates testosterone in the testes. This suppression results in a steep decrease of testosterone in the testicles and profound sperm suppression.

When taken continuously, the gel is both effective and reversible.

Like all participants, Seth and Caitlin Kinast were part of the trial for 20 months. For the first four months, Seth rubbed NES/T on his back and shoulders every day while the couple continued using other forms of birth control. This initial period, called the suppression phase, allows the hormones in the gel to decrease the body’s overall sperm production, but the patient is still fertile. Once sperm counts decreased to fewer than 1 million sperm per milliliter of semen, doctors gave the go-ahead for Seth and Caitlin Kinast to use NES/T as their only contraceptive for one year.

During that time, he had zero negative side effects, and she didn’t get pregnant.

Stephanie Page, an endocrinologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine, runs a NES/T trial site in Seattle and is the primary investigator for the entire Phase 2 trial. Because the trials are still ongoing, Page could not provide a precise answer for how effective NES/T is. Though, so far, she says, her team has been “extremely encouraged by the results.”

“I thought it’d be nice if I could take my fertility into my own hands.”

After his year-plus on NES/T, Seth entered the six-month recovery period when he stopped using the gel. His sperm count fully returned after four months. Following participation in the clinical trial, Seth and Caitlin Kinast became pregnant with their second child without trouble.

According to Diana Blithe, program chief of the Contraceptive Development Program at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), a part of the NIH, it takes about four to six months for sperm counts to return to normal after stopping NES/T. Blithe is also the trial study director. “Quite a few” couples went on to have children after exiting the trial, says Blithe, calling them “NES/T babies.”

“I feel as if we’ve made a huge leap that hadn't been made in all the decades I’ve been involved in this process,” she says.

What took so long?

Stephanie Page has been working in contraceptive clinical trials for more than 20 years. She’s worked on NES/T’s trial for eight of those years.

“There’s a lot of complexities to testing a male-directed contraceptive, because obviously the female is taking on all the risk, and the man is using the drug,” Page says. Male contraceptives are a unique case in which one person is taking a drug to prevent a condition in another person.

Another big issue, says Page, is that “we’re giving a drug to a person for no direct health benefit for themselves.” It’s not uncommon for doctors to prescribe hormonal birth control to women to treat issues such as menstrual irregularity, cramps, and acne.

In women, hormonal birth control has a slew of side effects, which makes it a double-edged sword. The perfect hormonal IUD for one person may be a nightmare for another.

For NES/T, though, this unpredictability hasn’t been the case so far.

As Seth Kinast shows, there may be plenty of benefits to taking male birth control besides pregnancy prevention. He wasn’t the only participant with such an experience.

“I thought it was too good to be true,” says Dev Bellman, who works in human resources in Seattle. Bellman, 30, enrolled in the trial in May 2019 after seeing a flyer. “I thought it’d be nice if I could take my fertility into my own hands.”

This trial came at a good time. His partner had just removed her IUD after experiencing what Bellman describes as “horrible side effects” that led her to believe she had the often painful uterine tissue-growth disorder endometriosis. Bellman, on the other hand, experienced little more than some skin sensitivity and heightened emotions during his 16 months using NES/T. Bellman remembers his friends were incredulous. They were convinced he’d suffer horrendous side effects, or become infertile.

Another participant, 25-year-old Ph.D. student Daniel Castaneda in Davis, California, says he had a “significantly positive experience.” He even persuaded another couple to join the trial based on his positive experience with NES/T.

John Reynolds-Wright, a sexual health doctor at the University of Edinburgh who helps run a U.K. site for the trial, says that his patients’ responses have been “overwhelmingly positive.” “They find it easy to use, not easy to forget it, they’re able to tweak it in so it fits into their lifestyle without having to make major changes.” The NIH’s Blithe also noted that since the trial’s start, side effects have been minimal.

One of the few inconveniences with adopting a daily gel application is that the participant has to wait two hours before exercising or going swimming so the gel has time to absorb. He also has to be careful that nobody makes skin-on-skin contact or the testosterone could rub off and possibly affect another person. Seth Kinast quickly learned to rub on his gel and then wear a T-shirt plus another shirt over it. He’d follow this by washing his hands with soap before going to help Caitlin Kinast with their kids.

Taking part in this trial was eye-opening for the participants in other ways, too.

“There’s so many things that women undergo when they’re on birth control, and I just wanted to understand,” Bellman says. “The experience nowhere near compares to what it’s like to be a woman, but it did give me introspect. I’m on birth control — given, mine is a shoulder gel.”

Part of these positive experiences could come from the type of people who volunteered to be in these studies. While this trial has been promising, it’s still small and self-selecting.

Some experienced no side effects at all, positive or negative. But there still was a tremendously positive impact on the partners. After his partner brought up the NES/T trial, Jake Burkhead, a 32-year-old software engineer in Seattle, agreed to start with a surprising assuredness. Once he learned to incorporate the gel into his daily routine, it was as if nothing had changed. For his partner, though, it made all the difference.

Burkhead’s partner, Caitlin Cronkhite, started hormonal birth control at age 17. Cronkhite, who is now 31 and works in tech communications in Seattle, was on some form of it until last year when they started the trial. She’s the one who came across NES/T.

“In a fit of rage about feminism and my experience with birth control, I was just like, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ I didn’t know what I was going to find. But I went a-Googling and, and that’s how we came across the gel study,” Cronkhite says.

Will NES/T make it to market?

Even if NES/T gets approved for Phase 3 trials, there’s no guarantee it will find commercial success.

“In the end, pharmaceutical companies need to make money,” endocrinologist Stephanie Page says. “Or, that’s their goal. Their goal is not to improve health. I mean, hopefully, they’re both.”

The reality is that pharmaceutical companies have a built-in market for female contraceptives, but choosing to forego male birth control altogether could seal a door they haven’t even opened.

Some doctors already see it as a promising medication. Urologist and male fertility specialist Rajiv Jayadevan, at the University of California, Los Angeles Division of Reproductive Endocrinology, says a birth control like NES/T is “a long time coming.” He believes NES/T could be an intermediary for those still uncertain about wanting children.

It could be another 10 years before NES/T comes to market — if it gets picked up.

“I think this would be incorporated into my standard counseling for contraception,” says Jayadevan. What’s more, he believes that once the product is commercially available, it will sell itself. “I think once a product is actually brought to the market, there will be a spike certainly in interest on a patient’s behalf.”

That market could grow, too.

“I don’t see why this has to be relegated to just those in a monogamous long-term relationship,” Jayadevan says. (Granted, right now condoms are the only birth control that prevents both pregnancy and transmission of STDs, so it would take quite a lot of trust to know that a male partner is taking NES/T correctly.)

Page underscores another important, overlooked point: “You’re preventing the life-threatening condition of pregnancy.” Even if a pregnancy is planned and wanted, it still puts the parent’s life at stake.

An unplanned pregnancy isn’t just about potentially birthing a baby nine months later, it’s about one person living with a risky condition for that duration first. Male contraceptives are meant to help the other partner take on a little more responsibility and take a little pressure off the other person.

The NIH has confidence in NES/T, based on how much funding its clinical trials have received: more than $12.6 million since the first year it received recorded funding in 2014. It’s difficult to parse the gender breakdown for NIH funding for contraceptive clinical trials. But overall, it seems surprisingly equitable: In both 2015 and 2020, the NES/T trial received over $5 million, more than half of the budget for contraceptive clinical trials the NIH set aside for those years.

There’s also the complex question of subsidizing the cost of NES/T, since female contraceptives must be fully covered by all insurance.

Advocacy may be part of the answer to persuading pharma companies, says Blithe of the NICHD.

Blithe thinks it could be another 10 years before NES/T comes to market — if it gets picked up. Best-case scenario and with serious financial commitment from a commercial partner, she says it could hit shelves by 2030, which is a ways off. Still, Blithe is more optimistic now than years ago about NES/T’s success.

“It’s unfair that men don’t really have that many options.”

Because of the continued success of the Phase 2 trial, Blithe wants to speak to the FDA to jumpstart the Phase 3 trial before the Phase 2 trial wraps up, which has an estimated primary completion date of September 2023.

“This is working way better than we predicted it might or even hoped that it would. We really want to move into Phase 3 sooner rather than wait,” Blithe says. A Phase 3 trial would likely take another four years, following at least 1,000 couples. “We’re hoping maybe August or September to have a conversation with [the FDA] and say, ‘Can we declare victory and go into Phase 3?’”

Once Jake Burkhead and Caitlin Cronkhite finish the trial, Jake plans to get a vasectomy. The currently limited birth control options available to men continue to reinforce the notion that since women are the ones who get pregnant, it’s their responsibility to prevent it. Providing men with more tools that are safe and effective could give them more agency over how they influence reproduction.

“Women live with these side effects every day, and no one seems to care, which is just, in my experience, fundamentally unfair,” Cronkhite says. “And I also think it’s unfair that men don’t really have that many options, the ones who care about controlling their own family planning journey.”