Planetary scientists have issued a tornado warning for Jupiter, with the discovery that magnetic vortices twisting down from the planet's ionosphere into its deep atmosphere are resulting in giant, ultraviolet-absorbing anticyclones each the size of our Earth.

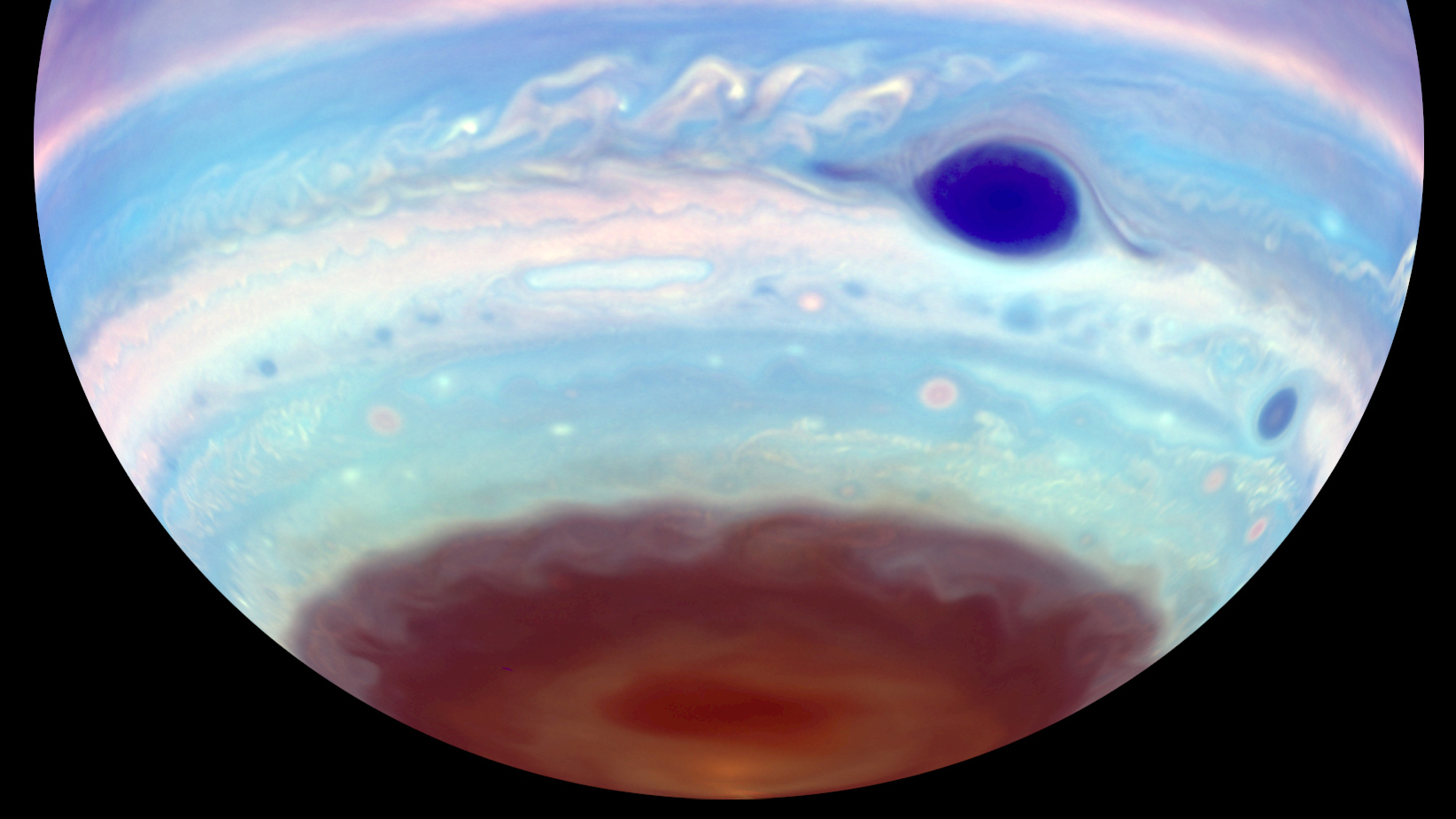

These anticyclonic storms manifest as dark ovals, and are visible as dense hazes of aerosols in Jupiter's stratosphere. However, they're only noticeable in ultraviolet (UV) light and were first seen at Jupiter's north and south poles by the Hubble Space Telescope in the late 1990s. They were then confirmed at Jupiter's north pole by NASA's Cassini spacecraft as it flew past in 2000 on its way to Saturn. But no one knew where the dark ovals came from.

Now, planetary scientists led by Troy Tsubota, an undergraduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, have figured out that the dark ovals are formed by swirling magnetic tornados produced when friction occurs between magnetic field lines in Jupiter's immensely strong magnetic field.

The key to understanding the dark, UV-absorbing anticyclones was found in the annual images of Jupiter taken by the Hubble Space Telescope as part of the Outer Planet Atmospheres Legacy (OPAL) project led by Amy Simon, of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. OPAL involves Hubble imaging each of the giant planets — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — once per year, to keep track of changes in their appearance.

Related: Jupiter: A guide to the largest planet in the solar system

"We realized these OPAL images were like a gold mine," said Tsubota in a statement.

In Hubble images of Jupiter taken between 2015 and 2022, Tsubota found a dark oval at the planet's south pole three-quarters of the time, but only once at the north pole in eight images.

As on Earth, Jupiter's magnetic field converges at its poles, and as on Earth, this concentration of magnetic field lines drives charged particles toward the polar regions, where they collide with atmospheric molecules to produce aurorae. On Jupiter, the auroral lights are detectable only in UV light, unlike the colorful displays we see in Earth's sky. For there to be a transitory phenomenon such as the dark ovals appearing at Jupiter's poles strongly suggested that it was connected to the planet's magnetic field, just like the aurora is.

Tsubota and his supervisor, Michael Wong, teamed up with Simon, plus planetary scientists Tom Stallard at Northumbria University in Newcastle and Xi Zhang at the University of California, Santa Cruz, to solve the puzzle of what causes the dark ovals.

Surrounding Jupiter, trapped within the gigantic magnetic field generated by the planet, is the Io Plasma Torus — a donut-shaped ring of charged particles spewed out by the plentiful volcanoes on Jupiter's eruptive moon, Io. Stallard suggested that friction between magnetic field lines in the plasma torus and in field lines closer to the planet in the ionosphere — an outer region filled with radiation belts containing more charged particles — could regularly instigate the formation of magnetic vortices that swirl down deep into Jupiter's stratosphere. These magnetic tornadoes would then stir up aerosols in the lower atmosphere, creating a dense patch of swirling, ultraviolet-absorbing haze that forms a dark oval. However, it's not currently clear whether the tornados dredge up the haze from deeper in the planet, or whether the tornadoes create the hazes.

"The haze in the dark ovals is 50 times thicker than the typical concentration," said Zhang. "Which suggests it likely forms due to swirling vortex dynamics rather than chemical reactions triggered by high-energy particles from the upper atmosphere."

Indeed, said Zhang, the observations indicate that the timing and location at which the dark ovals appear does not correlate with bursts of these charged particles. The dark ovals seem to take about a month to form and then dissipate within a couple of weeks.

Given the regularity with which the dark ovals appear, it would seem that Jupiter sits in the middle of its own magnetic tornado alley.

The findings were published on Nov. 26 in the journal Nature Astronomy.