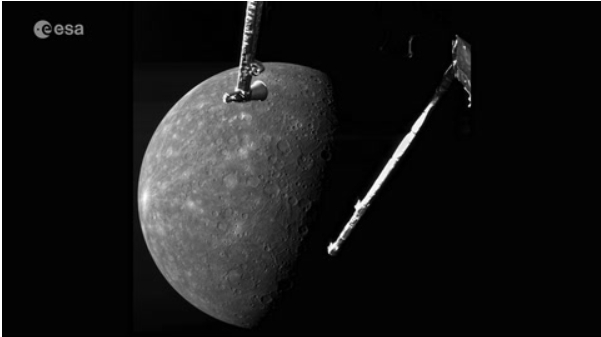

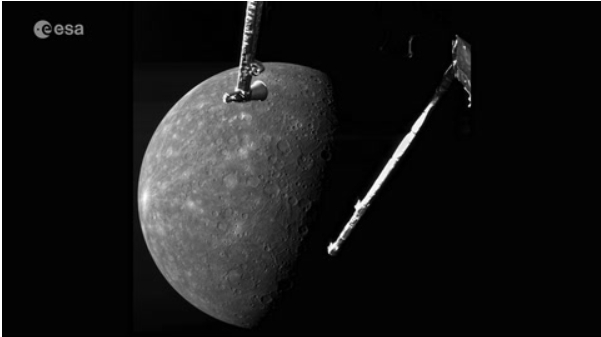

When the BepiColombo Mercury probe made its closest approach yet to its target earlier this month, the spacecraft not only captured the first clear view of the planet's south pole but also collected valuable science data that underscores just how sharply and rapidly its local environment changes in response to the solar wind.

On Sept. 4, BepiColombo conducted its fourth successful swing past Mercury, in a flyby that reduced the European-Japanese probe's speed and altered its direction, taking it a step closer to entering orbit around the planet in 2026. A preliminary analysis of data collected by 10 of the spacecraft's 16 instruments shows that the environment around Mercury varies significantly with occasionally unexpected features, mission team members said last week at the Europlanet Science Congress in Berlin.

Although BepiColombo flew through the same regions around Mercury during each of the previous three flybys, the probe's instruments recorded varying counts of particles in the bubble-like magnetosphere carved out by the planet's magnetic field, said Hayley Williamson, a senior scientist at the Swedish Institute for Space Physics and a co-investigator on BepiColombo's SERENA instrument.

During the fourth and latest flyby on Sept. 4, which took BepiColombo just 103 miles (165 kilometers) above Mercury's surface, the probe for the first time recorded planetary ions, which are charged particles wafting in Mercury's magnetosphere after being blasted from its surface by the solar wind. Puzzlingly, those particles appeared to split into two different energy levels shortly after BepiColombo's closest approach, Williamson said. All in all, it seems that Mercury was sporting a slightly different magnetic environment during each flyby.

Related: BepiColombo probe captures stunning Mercury images in closest flyby yet

"They all look quite different," she said. "It really shows just how dynamic Mercury's space environment is."

A day before BepiColombo's latest close approach, a pocket of high-energy particles from the sun hit the spacecraft and Mercury. Those particles would have dramatically affected the planet's magnetosphere and may explain some of the unexpected features in the data, although further analysis is needed before drawing any conclusions, Williamson said.

The latest flyby "was the closest a spacecraft has ever flown by a planet, including Earth," said Ignacio Clerigo, who is BepiColombo's spacecraft operations manager at the European Space Agency (ESA) in Germany. He credited the mission's flight control and dynamics teams for successfully carrying out the complex encounter that was 21 miles (35 km) closer than originally planned. "It's really an engineering achievement."

The unexpectedly close brush over Mercury's surface was due to the revised trajectory crafted by the mission team in an effort to overcome a glitch in the spacecraft's propulsion system.

In April, engineers determined that the electric thrusters in the spacecraft's transfer module, which rely on electricity supplied by the module's solar panels, were not operating at full power. Anomalous electric currents flowing between the probe's transfer module and a unit that distributes power to the rest of the spacecraft left less power available for the thrusters, prompting the team to come up with a revised route requiring lower thrust levels.

"It's upsetting, but we have a simple solution," said Clerigo. The revised route means BepiColombo will enter into orbit around Mercury in November 2026, 11 months behind schedule. The delay will not affect the mission's science objectives, ESA said in a statement earlier this month.

The next milestone for the $1.8 billion spacecraft is a swing past Mercury on Dec. 1 and another on Jan. 8, 2025 — amounting to three flybys in about four months.

"We have a very intense year ahead," said Clerigo.