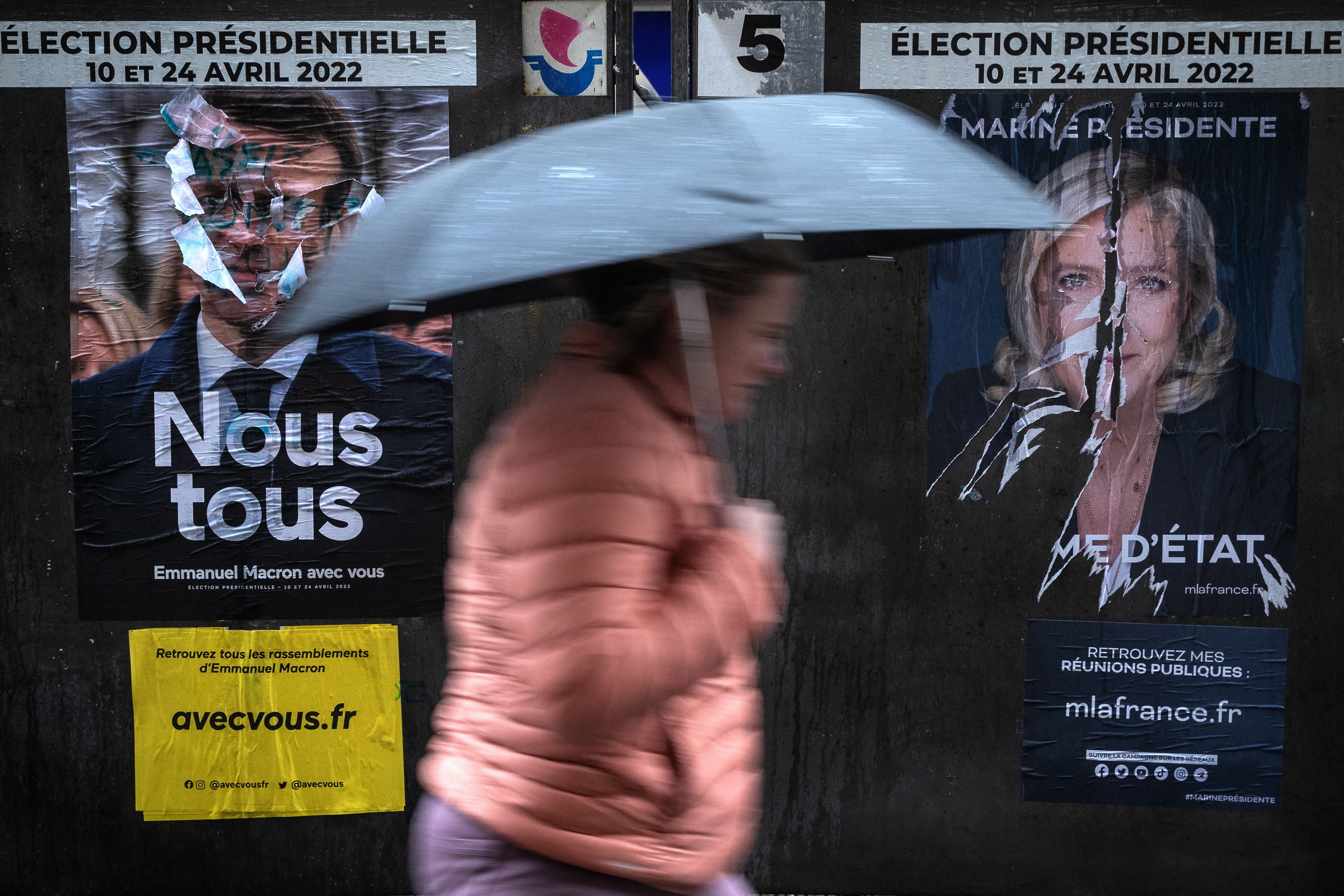

France’s Emmanuel Macron faces a gruelling two-week campaign season and a fight for his political life after coming out on top of the first round of presidential elections on Monday but facing a hostile, sceptical electorate.

To win against far-right challenger Marine Le Pen on 24 April, Mr Macron must stunt her momentum. But more crucially he must convince angry leftists, Muslims and ethnic minorities who voted for Jean-Luc Melenchon to back him after embracing neoliberal economic policies such as raising the retirement age and flirting with right-wing ideas on immigration and intellectual life.

“I don’t know what Macron can offer the left at this point because he has spent five years alienating them,” said Arun Kapil, who teaches politics and history at the Catholic University of Paris. “He’s made it very clear he doesn’t care about them and he doesn’t need them and doesn’t know how to talk to them.”

As election day approached, insiders close to the Macron campaign were alarmed and pessimistic about his prospects, though they have become somewhat heartened by the margin of his first-round victory on Sunday.

Interior ministry results showed Mr Macron leading all 12 candidates with around 27.6 per cent of the vote, compared to Ms Le Pen’s 23.4 per cent.

Nonetheless, Mr Macron is clearly in trouble. A survey conducted by Harris Interactive after polls closed showed him with a minuscule 51 per cent to 49 per cent lead over Ms Le Pen in the runoff, well within the poll’s margin of error.

And one stunning poll conducted just before the first round showed Ms Le Pen, heir to the once fringe far-right political dynasty of her father Jean-Marie Le Pen, narrowly defeating Mr Macron in a second-round matchup.

“Imagine Le Pen is elected in two weeks,” said Philippe Froguel, a 63-year-old scientist and government adviser who has been critical of Mr Macron’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic. “It will really be an earthquake. The value of the euro will drop. The Paris Bourse will drop, there will be a time of great uncertainty.”

Ms Le Pen’s surging candidacy has worried France’s neighbours.

A victory for the far-right candidate would have far-reaching geopolitical consequences. She has attempted to soften her anti-immigrant, anti-European Union and anti-Nato sentiments. But her National Rally party retains a platform of severely restricting immigration, and she has said she would outlaw the wearing of the Islamic hijab in public.

She remains beholden to Kremlin-linked banks for her political finances and is friendly with Russian president Vladimir Putin, whose war against Ukraine remains the most pressing international matter of the day.

A televised debate next week between Mr Macron and Ms Le Pen will likely produce fireworks and may sway votes.

“I am very worried,” Luxembourg’s foreign minister Jean Asselborn said on Monday, on the prospects of a Le Pen victory. “It would not only be a break away from the core values of the EU, it would totally change its course. The French need to prevent this.”

First-round results suggested a narrow path for a Macron victory that would entail him drawing votes from left-wing French voters who backed Mr Melenchon with about 22 per cent of the vote on Sunday.

The far-right candidate Eric Zemmour, with 7 per cent of the vote, has urged his supporters to vote for Ms Le Pen, while several other smaller right-wing candidates will also see their votes gravitate toward her.

Meanwhile, the centre-right and several left-leaning candidates, with a total of about 13 per cent of the vote, have urged their supporters to back Mr Macron, but that still means he must win over half or more of Mr Melenchon’s supporters to defeat Ms Le Pen.

After placing third in the first round, Mr Melenchon declined to endorse Mr Macron but urged his supporters to cast “not a single vote” for the far right.

According to the latest polling, more than a third of Melenchon voters will abstain, a third will vote for Macron and about a quarter for Le Pen.

“This election, we’re going to have to go out and earn it, because it’s not a done deal,” Mr Macron’s spokesperson, Gabriel Attal, said in an interview with France Inter radio on Monday.

The centrist Mr Macron faces a challenge not dissimilar to what US presidential contender Hillary Clinton faced in 2016, when she defeated social democratic candidate Bernie Sanders in primaries but then struggled to convince the so-called “Bernie Bros” to back her in the election against Donald Trump, a Le Pen ally to whom she lost.

Mr Macron is hampered by his and his surrogates’ attempts to lure right-wing voters by embracing conservative ideas on cultural life, including campaigns against so-called “Islamo-leftism” and “wokeism” on campuses and in cultural life in favour of a French version of secularism that appears directed at suppressing cultural expression by ethnic, religious and sexual minorities.

“It’s all going to come down to Melenchon’s voters,” said Mr Kapil, who runs a blog on French politics. “That’s how the election is going to be decided. Melenchon voters are faced with a choice of Macron, who they can’t stand, and Le Pen, who they hate even more.”

Surveys and exit polls showed that younger voters were supporting Mr Melenchon and Ms Le Pen in far greater numbers than Mr Macron, who was strongest among older voters.

“I am voting for Macron because we need someone who is capable of representing France on the world stage, of speaking to other countries and of representing France in Europe,” said Sussane Guelaine, a 95-year-old who was voting on Sunday in the Paris suburb of Montrouge.

At polling stations on Sunday, those who said they voted for Mr Melenchon were sanguine about the prospect of backing Mr Macron.

“Melenchon has good ideas; I don’t want Macron,” Mustafa Keju, a 37-year-old voter, told The Independent.

“If it’s between Macron and Le Pen, I would vote for Marine, because she deserves it,” he said, before dismissing his own words.

Even as they waited in line in front of public schools to cast their votes, many said they had yet to decide how to vote, underscoring a deeper crisis in French politics after the collapse of the centre-left and centre-right parties that have dominated the country since the 1960s.

Neither the socialist party of Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo nor the traditional Gaulist centre-right party of Valerie Pecresse managed to muster up the 5 per cent of votes necessary to qualify for public funding of their campaigns.

Even as she waited in line to vote, school cleaner Edwe Ouattara, 39, said she was unsure if she would vote for Mr Macron or Mr Melenchon.

“I work from 5am to 3pm every day, and I have a daughter, and I worry about her future,” she said.

Sorbonne University literature student Clotilde Guegan, 20, also said she would decide at the very last second whether to vote for the left or the centre.

“I am torn between voting for my ideas and voting strategically,” she said.