The first shot at parole has been denied for convicted murderer Mark Lundy, with the next chance coming up in nine months.

Two times convicted murderer Mark Lundy was vehement in his denial of offending in his first parole hearing this morning.

“Although I am convicted of murder, I have committed no offence,” he said.

Lundy was denied parole after his first parole hearing in 20 years, with the board citing gaps in his safety plan and a lack of introspection about past drinking habits as reasons for not giving him a release date.

The hearing, which took place on Friday morning at Tongariro Prison, saw Lundy’s bid for parole denied with another hearing set for May of next year.

The board said they had “considerable concern” about the lack of a safety plan for his release.

His case manager said he had not worked with him to put the requisite plan together - with the board suggesting the difficulties of pandemic restrictions may have prevented the job from being done.

When quizzed by the board about the safety plan, Lundy’s case manager said “it wasn’t something that was on our radar in terms of his treatment and in terms of assisting him”.

Lundy’s lawyer Julie-Anne Kincade QC said in her experience parole is frequently declined due to agency failures, such as treatment needs being identified at a very late stage or courses not being provided in a timely way.

“It is very disappointing if on top of that sort of failure, more basic preparation has also not been provided for the board’s assistance, such as the prisoner safety and/or release plan, which should be prepared by corrections staff working with the prisoner well in advance of a hearing,” she said. “Whilst Covid is often cited now as a reason, this is by no means a new problem and one that blighted many parole applications in the past.”

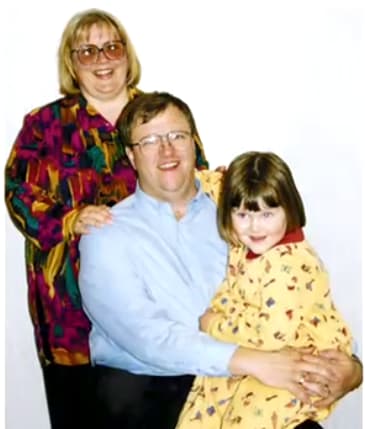

Speaking about the result, Lundy’s sister Caryl Jones said they have got used to the worst and today was no exception.

“We plan for the best and expect the worst,” she said. “We support him and love him and we’ll keep up the fight. We will always be here for him.”

Lundy was direct, calm and polite through the hearing, professing his innocence numerous times, going against a parole board that said it isn’t there to revisit his convictions.

Lundy was optimistic when first greeted by the board at the beginning of the hearing.

“I’m good,” he said. “I’m always good.”

Lundy’s lawyer opened the hearing by laying out seven reasons why he would not be a risk to the community, which the board said was their paramount responsibility.

Among these were good behaviour in prison, no previous history of violence, positive reports from prison staff, a low statistical risk of reoffending score, a low future risk of violence score and letters of support from friends and family.

Kincade said “perhaps most persuasive of all”, Lundy had been on bail from October of 2013 through to his retrial in February and March of 2015 and did not breach his bail conditions.

She said parole conditions were liable to be much stricter than the bail conditions he had seven years ago.

“Mr Lundy accepts the conditions suggested, but we suggest if the board does have any remaining concerns those conditions should ameliorate those concerns,” she said.

The hearing was then turned to the parole board, with each member having questions for Lundy.

He was asked what he expected from the hearing, to which he replied he had “absolutely no idea”.

“I've never been to a parole board before and this is all new to me. I would like a date,” he said.

The board then asked him whether he had completed the aforementioned safety plan, he said it was difficult to put together a safety plan for how to rejoin society as an offender when he holds that he committed no offence.

“If I had committed the offence, I would've plead guilty and I would've been out a long time ago,” he said, adding that he could have been eligible for parole five to eight years ago if he had gone with a guilty plea.

“But I have vehemently denied the offending because I did not do it… and there is nothing I can say to alleviate that for you,” he said.

The board said this was a moot point as being granted parole would have depended on the decisions of earlier parole boards.

Another board member said they had read reports that Lundy had an optimistic personality, and tended to retreat to his cell if upset.

She asked him to explain his behaviour at the funeral for his wife and daughter with respect to this.

“I think all of us have seen the conduct after the funeral, which is very different behaviour,” she said.

Lundy went through his limited memories of the day, saying he had no recall of the service and that one of his biggest regrets was not having a video recording of it.

"That day...my sister Caryl drove me to the church and I struggled to get out of the car, I was a psychological mess, a friend from Hamilton got me out and got me into the church hall, my next memory is about three hours later. I have no memory of the funeral and that really upset me,” he said.

“Well, I was interested in that, alright,” said the board member.

The board then had questions about Lundy’s drinking, as psychological reports had suggested the need for alcohol treatment.

The board said there was a difference between the self-reported amount of Lundy’s drinking and information gained from others.

Lundy admitted he was a heavy drinker, and said the difference in the reports may have come down to him drinking relatively less than some of the people in his past social circles.

“With the people I socialised with I was probably middle of the road…There were many people in our group who drank every night of the week. Christine and I might have nothing one week and out three nights the next,” he said.

He said drinking was part of the culture at the Palmerston North Operatic Society and the Eastman Rover Scouts, which he was a part of.

A member of the board asked him if there were people in the Operatic Society who drank less than him, which he said was true, although “there were people who drank a damn sight more than I did”.

They questioned him why he was a heavy drinker.

“People usually drink for a reason and it’s beneficial to know what that reason is.”

He said during the retrial he had not touched alcohol, recalling going out for dinner in Wellington and opting for ginger beer while those around him ordered beer and wine.

“Not drinking is not an issue,” he said.

Lundy said after being out on bail seven years ago that he would make attempts to appear before the parole board, as he decided being out of prison under parole conditions was better than remaining behind bars.

The board acknowledged Lundy has received accolades for his performance in the prison’s carpentry shop, although Lundy said any accolades he received were for his team rather than his work as an individual.

A prison officer said Lundy was a “model prisoner” who was trusted to work outside the wire, doing maintenance work in the prison’s master control, a “no-go area for most”.

However, Covid restrictions over the past few years have prevented reintegration activities to go on from Tongariro Prison, with Lundy’s monitored trips back into society being to the hospital.

Lundy detailed his plans for life upon release, saying he would like to start attending services at an Anglican church and doing carpentry with charity Men’s Shed. He said he would be wary of whether he was wanted at church services and other events, saying “I do not want to be where I'm not wanted”.

He was unsure about his ability to go back into the workforce full-time due to health concerns, but said he had some money in an account and would rely on support from friends and family.

He also mentioned an idea he had to start making clocks from pōhutukawa burl, which a prison staff member had told him he could sell for around $200 each after seeing his handiwork in the carpentry shop.

The board asked him how he would deal with the expected media attention. Lundy said he would direct all media requests through his lawyer.

“Very wise to have a plan about that,” said a board member.

The board raised the likelihood of parole conditions preventing free access to Manawatū, where the crimes he was convicted to occurred.

Lundy said he had a good amount of friends there, but they would have to come visit him elsewhere. His only reason for returning to Manawatū was to visit the graves of his family.

“I would like to go to the cemetery to see my parents and my girls, but that would be purely at the approval of my probation officer,” he said.

The board then questioned whether he would have financial issues upon release. Accusations of motives born from financial hardship had been floated by the Crown in the trial.

"I will not borrow money. So the financial issues cannot arise,” Lundy replied. “At my age, whose gonna lend me money anyway?”

The board then questioned his case manager as to why he had not worked on a safety plan. Lundy had previously mentioned that this case manager had been assigned to him 18 months prior, and due to Covid disruptions they had had little chance to work together.

“We have not had any discussions with regard to a safety plan... because Mr Lundy is in denial,” he said.

The board said people often do their own safety plans, alleging Lundy would have seen other people’s plans over the years.

Lundy said he had never read one.

“I know they have them and those people all have triggers for their offending. I have not offended, so there are no triggers for me… that I'm aware of,” he said. “So to the best of my knowledge, a safety plan is based around those triggers and how to avoid them. So I could not work out how to actually do a safety plan as such.”

Although his lawyer laid out that he had not had any misdemeanours during his time in prison, the board brought up a time when he sent another inmate mail using a pseudonym during his time out on bail.

Lundy said this was deceptive but when he promises something he feels he needs to follow through, and said a member of prison staff had advised him to use a different name.

“My word is my bond,” he said.

Kincade concluded by making three points about her client’s chances at parole.

She repeated he had not been manipulative or deceptive, and said there had obviously been issues that had prevented him from getting help with writing a safety plan.

“It’s not been ideal but I would hope the board would not hold that against him,” she said.

Finally, she stressed that Lundy would know to extricate himself from confrontations with the public.

“He's had 20 years in prison avoiding confrontations,” she said.

This was his first parole hearing in the 20 years since the murders of Christine and Amber Lundy, which he was first convicted for in March of 2002.

It’s been 20 years since Mark Lundy took his case to the Court of Appeal, with the hope it would overturn his conviction of murdering his wife and daughter with a tomahawk.

Christine and Amber Lundy were found murdered in their Palmerston North home in August of 2000, with the Crown holding that Lundy had travelled home from a business trip to Petone and back in one evening to murder his family.

Lundy was convicted in March 2002, which was followed by an unsuccessful appeal in August of that year, which saw his non-parole period increased to 20 years - a period which ends today.

Another appeal to the Privy Council in 2013 predicated on the time of the victims’ deaths, presence of organic tissue on Lundy’s shirt and the time Christine’s computer was turned off saw his convictions quashed in wait for a second trial.

The retrial in 2015 saw the window for the time of death expanded to 14 hours, with the Crown alleging Lundy may have returned to Palmerston North in the early hours of the morning to murder his family.

Evidence that placed the killings in the early evening were used in the Crown’s case this time. This included the barely digested meal from McDonald's in the victims’ stomachs and the testimony of a self-described psychic who said she saw a fat person in a blond curly wig running away from the area at around 7pm that Tuesday night.

Lundy was found guilty of both murders once more, and he returned to prison.

An appeal of his second conviction was launched to the Court of Appeal in October of 2017, but was dismissed a year later in October of 2018. A concurrent appeal to the Supreme Court was dismissed at the end of that same year.

Te Kāhui Tātari Ture - also known as the Criminal Cases Review Commission - is investigating an application for a review of the case, after which it will decide whether to refer the case back to the Court of Appeal.