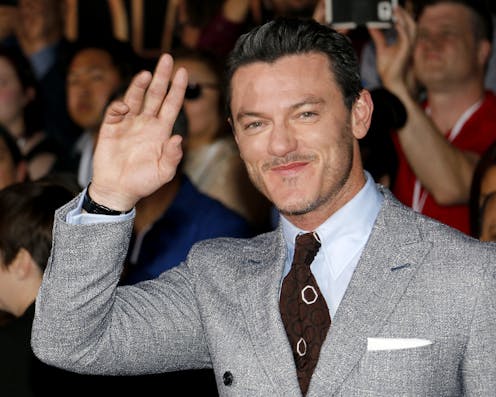

Hollywood actor Luke Evans writes candidly in his memoir about his experience growing up as a Jehovah’s Witness – and having to deal with religious and homophobic prejudice.

Evans describes a childhood where he was taunted by peers as a “Bible-basher”, and how he endured homophobic bullying. He writes:

I was bullied for being gay before I even understood what it meant. The worst nickname was “Jovey Bender”, because it combined two aspects of my identity that could never be reconciled. It wasn’t possible to be a “Jovey” and a “Bender” because being gay was strictly forbidden by the religion.

As an academic who works on religion and sexualities, my latest research focuses on gay ex-Jehovah’s Witnesses.

The Jehovah’s Witnesses, known for their door-knocking evangelising, pique interest because of the closed nature of their group. They are a fundamentalist and apocalyptic religious group organised into congregations, overseen by male elders – women are not permitted to be elders.

They refer to their beliefs and teachings as “the Truth”. There is a governing body, known as The Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society, which establishes all doctrine.

Condemnation

The Jehovah’s Witnesses have a distinctive social world. It’s an exclusive religious group that tries to set itself apart from contemporary society and culture. Research refers to Jehovah’s Witnesses as a “high cost” religious group, which means it demands a high level of obedience from its followers – and homosexuality is condemned.

Evans’ interview follows two other memoirs by gay ex-Jehovah’s Witnesses. In 2020, Mendez’s semi-autobiographical book Rainbow Milk was released to critical acclaim. Three years later, Daniel Allen Cox’s memoir detailed the ways growing up as a Jehovah’s Witness shaped him: “I spent eighteen years in a group that taught me to hate myself. You cannot be queer and a Jehovah’s Witness – it’s one or the other.”

Cox has a point. The reason these gay men are considered ex-Witnesses is that technically, one cannot be LGBTQ+ and a Jehovah’s Witness. As the official means of sharing Jehovah’s Witness beliefs, the magazine The Watchtower explains:

They gladly conduct Bible studies with homosexuals so these can learn Jehovah’s requirements, and such persons may attend meetings of the Witnesses to listen, but no one who continues to practice homosexuality can be one of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Evans’ interview recounts how he was terrified to go door knocking with his parents, in case one of his school bullies answered and hurled abuse at him. The teachings from the Witnesses affected his wellbeing. He recounts:

Every night in the congregation they read scriptures saying terrible things about the way I was feeling and who I was possibly turning into. All that was in my head was: if I don’t sort this out, I’m going to lose my mum and dad. I’m going to lose everything I’ve ever known and I’m also going to die at Armageddon, so I’m giving myself a death sentence unless I sort this out.

Importance of ex-member testimony

The only documented experiences we have about growing up LGBTQ+ as a Jehovah’s Witness comes from former members, like Evans, who have left – or been forced to leave.

But there’s a double bind here. There is a history of resistance to accounts from those who have been forced to leave, often referred to as “apostates” by the Witnesses. Ex-member testimony has often – and wrongly, I argue – been discredited among scholars of religion, as I highlight in my recent research.

Most importantly for LGBTQ+ people, ex-member testimony is the only glimpse we get into the effect of religious teaching that is hostile to non-heterosexual identities.

For LGBTQ+ former Witnesses, biography and memoir is a tool that allows them to write themselves into existence. Others, who are negotiating or navigating an exit from a high-cost religion, need these stories to help make sense of their own lives and experiences.

Making an exit

The method of exit is important. The terms “disfellowshipping”, “disassociation”, and “fading” represent different methods of exiting a religious organisation. Disfellowshipping involves the forced removal of a congregation member, often resulting in their ostracism and shunning by the community.

Jehovah’s Witness teachings describe disfellowshipping as a “loving provision” that “protects the clean, Christian congregation”.

Disassociation is when a Witness voluntarily resigns from the organisation, typically through a formal written request. For LGBTQ+ people, disfellowshipping or disassociation often leads to being labelled as “sexually immoral”, resulting in their expulsion and subsequent shunning by the congregation, including their close friends and family.

In contrast, fading is a more gradual and discreet approach, allowing Witnesses to distance themselves without going through the formal processes of disfellowshipping or disassociation. This method can be especially important for those who wish to maintain relationships with family and friends still involved in the organisation, as it does not involve an official removal.

Exit – forced or voluntary – for LGBTQ+ former Witnesses results in a number of vulnerabilities relating to housing, finance, emotional and psychological distress among other risks to wellbeing. Psychologists, such as Heather Ransom, have researched the cumulative effect on wellbeing for those who leave the Jehovah’s Witnesses, describing this process as “grief”.

In an interview with the Guardian, Evans recounts how he didn’t see a viable option in reconciling his faith and sexuality. This sentiment underpins the urgency for research about how strict, conservative religious frameworks can stifle personal identity, especially for children and young people who are LGBTQ+.

Chris Greenough does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.